He Is Risen!

“The Resurrection of Jesus is the crowning truth of our faith in Christ.” (CCC 638)

Easter is not just the most important day in the Church’s calendar — it is arguably the most important day in history. What happened on Easter was the goal of everything leading to it, and its reverberations continue to flow outwards until the Last Day, when the work of Easter will reach its definite consummation. “This is the day the Lord has made; let us rejoice and be glad,” we sing in the Responsorial Psalm. Happy Easter!

As St. Paul reminds us in 1 Corinthians 15 (though not in today’s readings), without Easter our faith makes no sense. It is worthless. If Jesus did not rise from the dead, Christianity is a fraud and Jesus is just another dead man. He has saved us from nothing, because death is the consequence of sin and, if the cause is not defeated, neither is its effect. But Christ has conquered sin and death. No one need be subject to sin and eternal death … unless he wants to be. “Thanks be to God! God has given us the victory through our Lord Jesus Christ” (1 Corinthians 15:57).

The Gospel reading that follows the three-year cycle of readings is the Gospel of the Easter Vigil. This year, it is Luke 24:1-12, detailing how Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James, and Joanna went to the tomb to anoint Jesus’ body, only to encounter two angels who proclaim Christ is risen. The women remember what Jesus foretold about his Resurrection and give the news to the Apostles. Peter rushes to the tomb to find Christ’s burial clothes and goes home “amazed at what had happened.”

(The Gospel for Easter Mass during the day is from John 20:1-9, where Mary Magdalene’s news causes Peter and John to run to the tomb. Comment on that Gospel and its place in art can be found here.)

Luke’s account generally follows the other two Synoptics. All three speak about women going to Christ’s tomb early Sunday morning to anoint his body. All of them agree (as does John) that Mary Magdalene was there. The three Synoptics agree Mary, the mother of James accompanied her. Matthew (28:1) mentions only those two. Mark (16:1) mentions three women, but calls the third “Salome.”

The Good News of Jesus’ Resurrection comes from a heavenly, angelic source for all three Synoptics. The one difference is that Luke (24:4) , unlike Matthew (28:2) and Mark (16:5), speak of two angels, not one. John (20:12) records that Mary encounters two angels. The angels proclaim Christ is risen, and that he will visit his Apostles. The angels in Luke make it explicit that Jesus had foretold his Resurrection.

The importance of Peter — as head of the Apostles and rock of the Church — being a witness to the empty tomb is affirmed in both Luke and John, the two Gospels in use today.

I note Luke’s mention of the number of angels (corroborated by John) at the tomb because it affects the choice of artwork to illustrate today’s Gospel.

Depending on the Gospel inspiring a particular artist, you might have one angel at the empty tomb or two. Other artists have depicted two angels, but not necessarily in the Gospel’s context of the empty tomb scene. Nineteenth-century Danish artist Carl Bloch’s “Resurrection,” frequently used in Easter art, depicts two angels, but at the moment of Resurrection itself, in the presence of Christ, not of the women. Late French Baroque painter Pierre Parocel and 19th-century German painter Julius von Carolsfeld give us two angels, but in the Johannine context with Mary Magdalene alone. Other artists depict two angels lamenting the dead Christ in the tomb, e.g., Bellini, Veronese, and Manet.

Two angels in conversation at the empty tomb with the women who have come to anoint Jesus were depicted by Flemish Baroque painter Peter-Paul Rubens (1577-1640) and Scottish painter William Brassey Hole (1846-1917). We’ll focus on Rubens.

Rubens in fact painted this scene at least twice. His earlier work (ca. 1611) is in the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena, California. The work we are considering is said to have been painted “by 1640,” i.e., by Rubens’ death. Comparing it to the earlier painting shows affinities, i.e., the painting we are considering reproduces the same two angels and the same five women, but expands the tomb and softens the colors of the painting. (The woman in the center who, according to the Norton Simon commentary is the Virgin Mary, also apparently changed her dress).

Rubens’ tomb is a two-room structure: an external arrival area, out of the elements, and the actual chamber where the body was laid. The angels stand atop the slab that had sealed the door. Their celestial light, almost cloudy (clouds are the sign of the Divine Presence in the Bible) shields that empty inner tomb. The two angels convey their Good News, their Gospel, to five women which, as noted, presumably includes the Virgin Mary (modeled, as Norton Simon notes, on a Roman statue to modesty) and counts Salome and Joanna separately.

If they are Lukan women (given the number of angels), they certainly don’t seem “terrified and bowed their face to the ground” (Luke 24:5), something a pious Jew would have done in the face of the heavenly. Compared to the Gospel accounts, where the women seem afraid (Mark 16:8, Matthew 28:8), this quintet is remarkably composed, the supposed Mary receiving the news as if “she was pondering all those things in her heart” (Luke 2:19) and aptly not being afraid (Luke 1:30). These women strike me more like the Mary Magdalene of John 20:11-13, so heartbroken in love with the supposed theft of Jesus that even two angels talking to her don’t seem to phase her, or the women of Matthew 28:8-10 — afraid but filled with joy — both attracted to yet afraid of their encounter with God, the Mysterium Tremendum et Fascinans.

On the left, the entrance to the tomb from which the stone had been rolled back leads down a path to Israel (Mark 16:7) … and the world (Matthew 28:18-20). In the painting, it serves to take us out of the enclosed tomb, expanding our horizon.

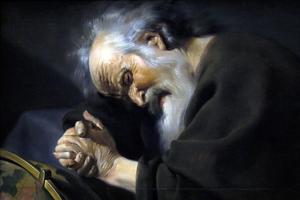

His figures are energetic, dynamic and full of life. They also tend to be large, not just in height: attractively plump and full-figured has passed into English in the adjective“Rubenesque,” apparent in all the figures in his painting.

Rubens, the leading painter of the Baroque in the Low Countries, studied in Rome but spent most of his artistic career in Antwerp (now Belgium). He was a key force in the Catholic Counter-Reformation.

- Keywords:

- resurrection

- Peter Paul rubens

- scriptures & art

- easter