Thomas More’s Saintly Silence

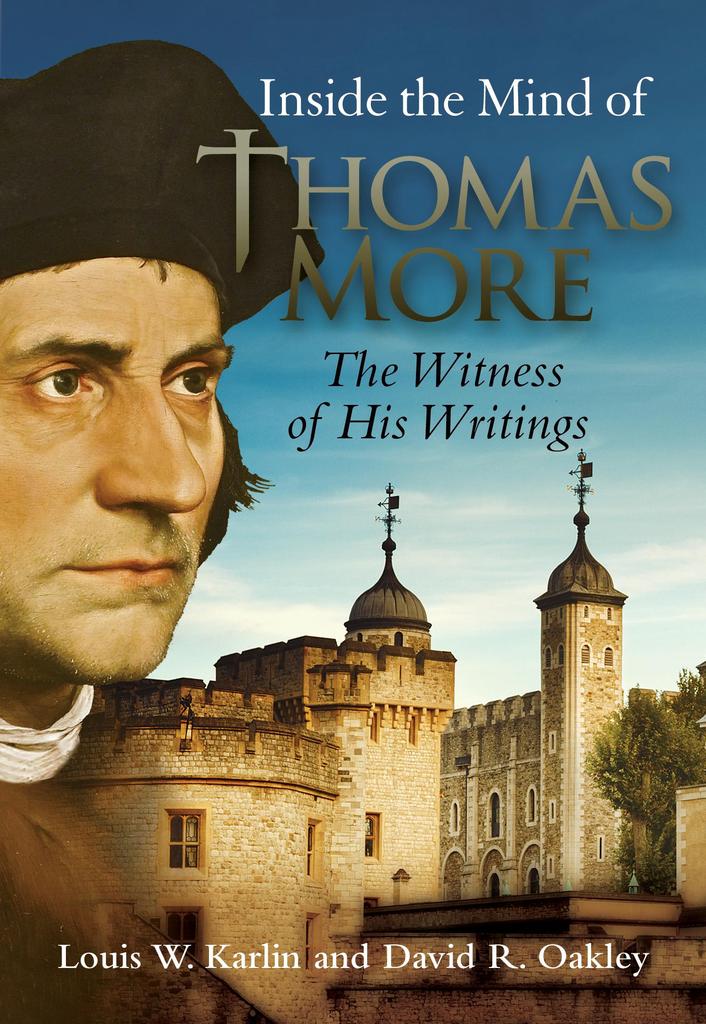

BOOK PICK: Inside the Mind of Thomas More: The Witness of His Writings

Inside the Mind of Thomas More

The Witness of His Writings

By Louis W. Karlin and David R. Oakley

Scepter Publishers, 2018

130 pages; $11.95

To order: scepterpublishers.org or (800) 322-8773

Conscience and silence: These are the keys that unlock the door to enter the mind of St. Thomas More.

Authors Louis W. Karlin and David R. Oakley explore these and related concepts to help the reader understand why Thomas More acted as he did at the crisis of his life as a loyal subject servant of King Henry VIII and as a Catholic Christian.

Fellows of the Center for Thomas More Studies, they are familiar with his life and works; as attorneys, they are fascinated by the legal and political issues involved in St. Thomas More’s arrest, interrogations and trial and his legal strategy and defense. In a rather brief book, they cite several of his works that have been updated with modern English spelling and usage as evidence of the prudence and fortitude with which More faced this crisis.

This is not a biography of More, nor is it an in-depth study of his works from The Life of Pico to The Sadness of Christ. In each chapter, the authors give the historical, political and legal background to an issue, examine More’s actions and reactions, and then present passages from his works to explain those actions. They also cite sources like son-in-law William Roper’s The Life of Sir Thomas More, the Catechism of the Catholic Church and several studies of More’s life and public career.

In the first chapter, for example, Karlin and Oakley demonstrate how St. Thomas More’s understanding of conscience accords with the classic Catholic understanding of that internal guide to doing what is right and avoiding what is wrong, using the Catechism of the Catholic Church for evidence.

Subsequent chapters tell the story of his resignation as chancellor, his imprisonment in the Tower of London, his trial and execution July 6, 1535, and a concluding discussion of how to square More’s prosecution of heretics with his attempts to appeal to conscience and silence to save his life.

Karlin and Oakley briefly examine More’s legal career before he became chancellor, succeeding Cardinal Thomas Wolsey. They note that More’s involvement in Henry VIII’s “Great Matter” regarding the validity of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon was limited to giving Henry his private opinion on the matter according to his study of Scripture, the Fathers of the Church and the councils of the Church. As chancellor, More had not taken up Cardinal Wolsey’s efforts to procure the annulment of Henry’s marriage to Catherine; Thomas Cromwell took over those duties. But More was honest and direct with Henry: “He did not shy away from giving the king an answer — repeatedly — that Henry did not wish to hear.”

As the authors note, More was able to give that answer, not saying what he knew Henry wanted to hear, because More followed the example of Cicero in public service. He recognized that he had abilities that would serve the common good, but he also knew the limits of those abilities and could step back from public service without regret. Examples from his History of Richard III and Utopia demonstrate More’s balanced approach to serving his monarch to make things better in England. Once the bishops offered their “Submission to the Clergy” May 15, 1532, More recognized that he could no longer make things better. If he continued to serve Henry VIII, he would be involved in making them worse.

More’s attempts to maintain silence as a defense against Henry VIII and Thomas Cromwell’s demand that he swear the “Oath of Succession” are the center of the chapters describing his imprisonment, trial and execution.

As Karlin and Oakley emphasize — and this is an important detail throughout Robert Bolt’s play A Man for All Seasons — More never shared his thoughts about the succession or Henry’s supremacy with anyone.

He maintained that he was never malicious or treasonous: He was silent. Unfortunately, “This was not the position of the Crown. ... More [had to] conform his conscience to the law of the realm.” The authors explore these ideas in detail as legal and spiritual issues. While More wanted to serve his king and his country, to love his family and protect them, he also wanted to live eternally in heaven with Jesus. He was certain he was following his well-formed conscience as God wanted him to, and he could not deny that truth without endangering his immortal soul.

As always, More’s dilemma is fascinating; Karlin and Oakley provide cogent background to help the reader understand it better so that we may know “the correct personal response in a conflict between the demands of conscience and human law: to resist shrewdly, but never to cooperate in evil at any cost.”

Stephanie A. Mann writes

from Wichita, Kansas.

- Keywords:

- book picks

- st. thomas more

- stephanie mann