The Man Who Rebuilt Steubenville

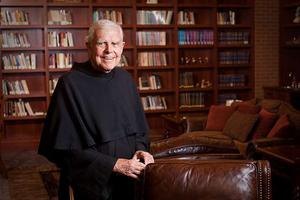

Father Michael Scanlan looks back on a career that included an early friendship with Avery Dulles, 42 years at Franciscan University and leading the charismatic renewal.

[Editor's note: This interview originally appeared in the Register on May 31, 2011.]

STEUBENVILLE, Ohio — Father Michael Scanlan’s name has become so closely linked to Steubenville, Ohio, that it’s a bit surprising to learn that he grew up in midtown Manhattan.

The Third Order Regular Franciscan has spent 42 of his 47 years as a priest at Franciscan University of Steubenville and played a large part in bringing the college back from near death.

This summer, though, Father Scanlan, 79, is retiring from his post as chancellor, a position he has held for the past 11 years. Before that, he spent 26 years as the university’s president.

An early leader in the Catholic charismatic renewal, Father Scanlan was instrumental in turning around a struggling university. During commencement exercises on May 13-14, Father Scanlan was given the title president emeritus of Franciscan University. He spoke with Register senior writer Tim Drake about his contributions to Catholic higher education.

Where are you from originally? Tell me about your family.

I grew up in midtown Manhattan. I attended boarding schools all the way through elementary and high school. I have one brother. I celebrated his wedding, and all of his children have come to Franciscan. My mother worked for a while as a secretary in the Empire State Building. My father was in imports and exports and worked out of Mexico City.

You’ve been a priest for 47 years with the Franciscan order. What led to your vocation?

It was the experience of God calling. I experienced it first while at Williams College in Massachusetts. One of my roommates was [the late owner of the New York Yankees] George Steinbrenner. I was receiving some very confusing teachings in philosophy, so one day I went out and spent a whole day and night in the woods. There, I heard God saying to me, “You can trust the Catholic Church as a truth-telling institution.” After that, I read everything I could find. I went to the New York Public Library reference librarian, and he gave me all kinds of great reading material from John Henry Newman and G.K. Chesterton. Before I knew it, I was elected the president of the Newman Club, and I was on the way, with a great sense that God would lead my life.

I thought my life was set. I was in ROTC and was supposed to go into the Air Force. I was engaged to be married. The night before I was to report for duty, while at my fiancée’s, I got a call not to report for duty. Congress had cut the budget, and I was told to stand by.

So, I decided to go to Harvard Law School. That first Lent I decided to get serious and began praying the Rosary and going to Mass every day. That’s when I heard God ask, “Will you give me your whole life?”

Once I said “Yes” to that, I had a sense of the presence of God. I ended up being called to the military afterwards. I was serving as a judge advocate in the Air Force and had a job waiting for me on Wall Street. The day I passed the military bar and became fully qualified, I sensed God saying, “Be a priest in community.” I said “Okay” and began pursuing that.

I didn’t know any religious communities other than the Jesuits, so I contacted them, and they put me in touch with Father Avery Dulles from Harvard, who had just been ordained. I went to visit him, and he told me, “Mike, a vocation is the restless Spirit of God within you. When that Spirit settles and is at home, stop and join the group where you are.”

I visited the Jesuits and the Dominicans, but it was when I visited the Franciscans that I felt at home and at peace. I joined up and never questioned it.

How bad was the situation at Franciscan University of Steubenville when you got there?

We had two empty dormitories. The local banks wouldn’t lend us any money. While at a bank to cash a check, the teller asked the banker whether they were even accepting checks from the university. We were listed in an educational journal as one of 13 colleges expected to close by the following year. It was a warning to investors and benefactors not to waste their money. Quite a number of faculty were resigning because they felt it was hopeless. The most telling feature was on my first day as president — they had a “For Sale” sign in front of our largest residence hall. The first thing I did was pull up that sign. I told folks, “Even if you’re going to die, you don’t advertise it.”

What were the biggest obstacles to turning Franciscan around?

The first strong opposition came from the faculty. There were a couple of young faculty members who objected to the changes. They introduced a resolution of no confidence in the president. The most senior faculty member said, “Before he came, we had no hope. Now we have hope. So, why don’t you leave, and he can stay?” That set out before everyone: What are we going to complain about, if we had no hope before?

There were also some young members of the Franciscan order who couldn’t trust enough in what was happening. About five hung on and believed in sticking together for the change. I wasn’t standing alone.

You’ve spent a total of 42 years at Franciscan in various roles. What do you see as your greatest accomplishment?

The thing I am most happy that I did was pray hard for what God wanted. I would spend three or four hours in the morning in prayer before I would go to the president’s office. I knew that God wanted to change things in the university, and I needed the same kind of assurance for what God wanted for the university as from what God wanted for my life.

What stands out is that it was God who was inspiring and leading me. I was just trying to be faithful. As I look back, I realize that we had to come up with a God-inspired mission. That mission was the same focus of a charism as the New Evangelization of Pope John Paul II. He was so instrumental in everything he would say and encourage that we could continually draw upon his pronouncements for what we wanted to be and what we wanted to follow.

The Steubenville youth conferences, which you started, have become very popular. How did those get started, and did you expect them to be so successful?

I was asked by some leaders in the Catholic charismatic renewal if I could put on a conference for priests to enable them to understand what was happening in the charismatic renewal. I said, “Sure.”

Our registrations grew so much that it was larger than anything our halls could handle, so we ended up putting up a tent. After the first conference, we had a general discussion. One priest said, “This is just what we need for our youth.” I asked, “How will we get the youth?” The priest said to his brother priests, “We’ll send them, right guys?” And they went home and promoted the youth conference to their youth groups. That’s how we got into the youth ministry and youth conference business.

I expected, when it was so successful, that it would be copied in other places, but two things surprised me. I was surprised that they kept calling them Steubenville conferences, even though they were being held in other dioceses. Apparently, youth hadn’t responded to some of the diocesan youth rallies, so they wanted to indicate that these were something different. We didn’t create the conferences for enrollment purposes, but it sure made a difference. The second surprise was the missionary zeal. So many of our students had done mission trips to Central and South America, and also in Chicago and New York, and they were enthusiastic to proclaim it to others. That drew youth to the conferences and drew students to campus.

Key to all of this was having a very solid theology department that would teach everything that would be consistent with what the students were experiencing. When I arrived, there was a philosophy and theology department, but no theology major. One of the full-time theology professors wasn’t even Catholic and didn’t support Catholic teachings, so it was awkward. We had to bring in new blood from outside. I personally recruited the first few new faculty members, and they became the foundation.

You were one of the leaders in the Catholic charismatic renewal. What do you see as some of the fruits of the renewal for the Church?

Certainly, the most obvious thing was the rediscovery of the charisms that had been a part of the Church in earlier times. Secondly, the desire for community, whether it was in a parish or a diocese; there was a desire to be joined and bonded together. Third, the desire to evangelize.

Members identified with the Pentecostal experience of the disciples and apostles: that we should be willing to go and witness in the same way they did. Finally, they wanted the Church as an anchor. It yielded great fidelity to the Pope and the magisterium. That was a surprise to a lot of people, because, initially, there was an identifying of Pentecostal groups as being independent and not submitted. The leadership, though, moved toward a clear commitment, and I was asked to preside at the first assembly of the Catholic charismatic renewal at the Vatican in 1975.

Early on, there was a fair amount of suspicion of the charismatic renewal, wasn’t there?

Yes, but Pope John Paul II was very encouraging. That really made a difference, and the Popes have continued to regularly encourage the Catholic charismatic renewal as a blessing for the Church. There were obviously many bumps and potholes in individual dioceses and some rough times in getting some bishops’ approval and endorsement. The pastors were even tougher than the bishops, but the Popes happily have an unbroken trail of encouraging the movement.

Another initiative of yours was the household system at Franciscan. Did that come about as a result of your own life in religious community?

That was part of it, but I also had visited Ann Arbor [Mich.], and I lived with some young men who were students at the university and were living together. While their university had nothing to do with it, I saw that this was just what I wanted — something that would take the good and the blessings of fraternity life and root it in faith and moral living, so students could avoid the pitfalls.

At the end of the fall semester, in January of 1975, I announced across campus that I wanted to meet with the entire resident student body. Just hours later, they showed up in great numbers. I told them that I knew they were lonely and restless and needed good fellowship, so I announced that there would be a couple of model households. I told them that by the following September every student needed to live in a household or they wouldn’t be invited back. The situation on campus required strong action and I knew that we needed to do something. I have to admit that I didn’t even consult the faculty, because I knew it would be debated endlessly. They were as surprised as the students.

When I was on campus last September, I couldn’t even get into the Portiuncula for prayer, because there were so many students praying at Eucharistic adoration there. Franciscan was one of the first colleges to have perpetual Eucharistic adoration. How did that come about?

Even though people in the beginning would say, “Oh, that’s a charismatic thing,” it was the result of grace. It was a movement by the students that followed the building of the Portiuncula.

We were having adoration times more frequently and longer in the side chapel of Christ the King Chapel, but with the building of the Portiuncula, there was an immediate thrust by the students for perpetual adoration.

You were involved in the start of so many initiatives and endeavors. How did you see your role in all of it?

I kept identifying it as the New Evangelization. The charisms of the Church were being stirred up again by Pope John Paul II, and we were being called to be a part of that. The Holy Spirit was using these gifts to bring new life and greater evangelization to his Church. It’s all been a grace.

Do you think that your work at Franciscan had an impact on other institutions of Catholic higher education?

Yes, particularly at the new, younger Catholic colleges. They have been greatly encouraged to go ahead and stand fully with the Church. They’ve been encouraged in what we and Pope John Paul II called “dynamic orthodoxy.” They’ve had a much better emphasis on evangelization. I’ve had some administrators contact me to find out how they can implement the household system. Some are trying to gradually evolve into something like that, but it can be a difficult process.

I understand that you’ll be going back to the Third Order Regular Sacred Heart Province’s motherhouse in Loretto, Pa. What will you miss the most about Franciscan?

I’ll miss the people here. The students are such a great group of fervent and excited people that I just love being with them and working with them. I’m scheduled for retirement, and yet I have this status as president emeritus. We have to work out how often and for how long I can be back here, what the rhythm will be.

At the end of June, I’ll go to the motherhouse. I’m expecting to come back to the campus many times during the year for different functions, but that hasn’t been worked out in detail yet.

Register senior writer Tim Drake writes from St. Joseph, Minnesota.