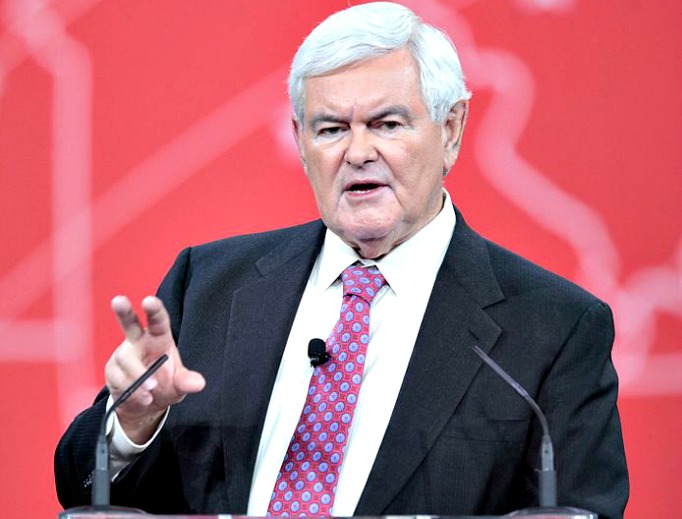

Newt Gingrich on Politics, Faith and the 2016 Election

During a pilgrimage to Rome, the Catholic convert discusses key political issues, how becoming Catholic has influenced his own beliefs, and Donald Trump’s lewd remarks about women.

ROME — As the U.S. presidential election draws closer, the Register caught up with former Republican presidential candidate and erstwhile Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich.

In this Oct. 7 interview during a pilgrimage to Rome, Gingrich, a historian and convert to the faith, discusses his concerns about this year’s election in light of the next president’s possible choices of Supreme Court justices, why religious freedom will be one of the most important struggles for freedom over the next 50 years, and how his Catholic faith impacts his politics.

He also shares his views on which issues should animate Catholic voters the most and why he believes a Catholic politician must be consistent about his faith in the public square. And, commenting immediately ahead of the second presidential debate on Sunday, the prominent Donald Trump supporter responded to a question about the Republican candidate’s broadly condemned taped remarks about sexual relations with women.

First of all, what is your reaction to the leak of a lewd conversation Donald Trump made in 2005 but was only broadcast last week?

This is a methodical lynching by the anti-religious left to cover up the horrifying statements of Hillary Clinton in various secret paid speeches. Trump’s comments were disgusting but do not represent who he now is or what kind of president he would be. Tonight’s debate will teach us a lot.

In what ways are the role and the obligations of a Catholic politician today different from his or her non-Catholic counterpart? How do you anticipate this might change in the future?

I think, ideally, any government leader is shaped by the core of their beliefs and I think, in that sense, to be Catholic is to have a very deeply held set of 2,000-year-old beliefs about the nature of human beings, about our moral obligations, about when life begins, about a whole series of issues, some of which lead to conflict. You have many conservative Catholics, for example, who are very strong on the right to life for babies but not very strong on the right to life for murderers, so they accept the death penalty even though it’s technically against the Church’s doctrine.

The great, rising crisis in America is the totalitarian threat against religious liberty, and if you look, there’s a Massachusetts commission on transgender rights, which is talking about regulating what you’re allowed to say in church — for example, if you can really raise the question of whether Our Father is a violation of gender behavior. Duke University now has a woman’s project to train men out of their “superiority.”

So you see the whole secular, almost classic, almost French Revolution, creation of a man-centered, human-centered world in which humans get to define the new rules and the new patterns, and it has nothing to do with the natural law, nothing to do with God. This will be one of the most important struggles for freedom in the next 50 years. It will literally define the future of America over the next 50 to 100 years.

The Trump campaign has launched an energetic effort to court Catholics. After months of no mention at all, why are Catholics suddenly important?

Well, Catholics were always important; it’s just a question of the sophistication of the campaign. Trump is a very gifted amateur who had no notion of the scale of the presidential campaign, how complicated it is, how many different groups you have to talk to, et cetera. I think he has learned a fair amount about that.

And I think on things like the nature of the Supreme Court, the gap between who Hillary would appoint and who Trump would appoint is so breathtaking that it’s hard for me to understand how any seriously committed religious person of any background — Catholic, Protestant, Jew — could vote for Hillary because she’s going to create a secular court designed to imposed a secular totalitarianism that will profoundly change the nature of America.

What issues, in your view, should concern Catholic voters most? Prudential matters related to the economy, national security for instance, or those that promote immorality and intrinsically evil acts?

First of all, you have a president for four years, but you could have a radical Supreme Court for 40 years, so the court is, in many ways, the most institutionally profound challenge that we’re facing.

Second, you have to take foreign policy seriously. I’ve written a lot of stuff and I do two free newsletters a week for Gingrich Productions, and I’ve written a lot about a “two-front war.” You have a secular offensive in Europe and America, and you have Islamic supremacism. They’re both on the offense, and we have not yet found our footing as Christians — and for that matter as Jews — to stand up against this onslaught. It is a very serious problem because you’re fighting two fronts simultaneously.

How would you respond to another Catholic politician who uses the claim that they cannot bring their faith into public life and so publicly support things like abortion while being “personally” opposed to them?

I don’t understand it. I don’t mean this in a harsh way, but tell me what you really believe. If you really believe what the Church teaches, that life begins at conception, then by definition, abortion is murder. Now you may decide that there are reasons for the murder, you may decide on having exceptions for rape and incest, you may decide to have an exception for this, that and the next thing. But the exceptions are to permit murder, and so when someone says to me, “You know, I really believe in the same thing that my Church teaches, but it doesn’t affect my public policy,” [I ask]: “Well then, what is your public policy based on?” I mean, if public policy has no rooting in belief, not even morality, just belief — is the sky blue? Well, it could be, but if you really want it to be purple and if it will make you feel better, I’ll say it’s purple — well, that’s just intellectual chaos.

And, of course, left-wing Catholic politicians have been sliding down this road since at least World War II. They’ve done it in Europe; they’ve done it in America. What it does, of course, is that it dissolves the religion, because then you have to say: “So, tell me what it is you believe in enough that you’d risk your career [to defend it].” And it turns out not much, in which case it turns out they’re actually belief-less. They’re full of piety but lacking in belief.

How has being Catholic altered your approach to politics and living your faith in public service?

I would say two characteristics. First, I come out of a Protestant background, so I have a pretty strong feel for the two great wings of American Christianity. I think Catholics are more communitarian. I’m stunned at all the things Catholics do, and this trip is an example — the number of things we do together, the degree to which there is a community and family, it’s like a gigantic, extended family.

Second, Catholicism is based in a very fundamental way on the inherent belief of sinfulness, that we all sin, that we all fall short of the glory of God, and that we begin to approach the mystery of the Sacrament by saying, “Here are the ways I have fallen short, in what I do, in what I fail to do,” and, as they’ve added in recent years, that it’s all my fault. I feel either John Paul II or Benedict thought we weren’t quite getting that [laughs].

Msgr. [Walter] Rossi, my mentor in joining the Church, we were one day sitting and talking, and I said to him, “So what you’re really saying to me is, when I walk down the aisle you are re-presenting Christ, you’re not representing Christ.” I knew this historically having studied the history of the Reformation and the whole argument about whether, in fact, whether there’s a transformation at the moment that the bells are rung. The Church’s doctrine is that you and I have the opportunity to have Christ in us and to renew that as often as we want to go to Mass.

And that also explains some of the depth of Catholicism historically, because if you belong to a religion which says your Savior is within you, and you relax and allow that to be true, then you are in fact never truly alone. I didn’t get that before converting. I knew the words, but I didn’t know the experience, if that makes any sense.

It’s only something you fully realize once you’re in the Church.

Yes, and that’s not to any way diminish the deep faith of Protestants and the many, many good friends I have who are Protestant and who are at least as worried about the country as Catholics are. They are deeply, deeply, deeply concerned about what is happening both in Europe and America.

Which living U.S. Catholic in politics impresses you the most and why?

I don’t think I could answer that question. There are people, intellectuals, George Weigel, for example, who are so profound and so smart that they impress me, but I don’t think in terms of Catholic politicians per se. It may be part of the American tradition.

Edward Pentin is the Register’s Rome correspondent.

- Keywords:

- donald trump

- edward pentin

- election 2016

- newt gingrich