Holiness Amid the Holocaust: Franciscans Host Exhibit of Former Auschwitz Prisoner

A moving tribute to the millions of victims of the Third Reich, including St. Maximilian Kolbe.

“Why does a loving God allow suffering?”

Negatives of Memory: Labyrinths, an art installation by Polish Catholic artist Marian Kołodziej, a former prisoner of Auschwitz, responds to this question. His exhibit, located at the Franciscan convent in the Polish village of Harmeze, harrowingly evokes the Golgotha of concentration-camp life, simultaneously emphasizing Christ’s oneness with the victims and the saintly witness of St. Maximilian Kolbe, whose feast day is Aug. 14.

Although Auschwitz-Birkenau is a symbol of the Nazi Holocaust, it was originally built to terrorize non-Jewish Poles, who made up most of the camp’s inmates until 1942. According to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, more than 1 million Jews were sent to the camp, 960,000 of whom died. Non-Jewish Poles, however, made up the second-largest group of victims: 140,000 to 150,000 people were deported to Auschwitz, of whom 74,000 were killed.

Marian Kołodziej was part of the first transport of prisoners to Auschwitz in 1940. After Nazi Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, 18-year-old Kołodziej tried to escape to France, where the Polish Armed Forces in the West were being formed to fight alongside the Allies. However, he was caught by the Germans and deported to Auschwitz. His prisoner number, 432, frequently appears in his art.

The artist was a prisoner of six concentration camps: Auschwitz, Gross-Rosen, Breslau-Lissa, Buchenwald, Sachsenhausen and Mauthausen-Ebensee, which was liberated by Gen. George Patton’s American Third Army.

After the war, Kołodziej studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow. Upon graduating, he moved to Gdansk. He became a famous film and theater set designer and designed the altars where St. John Paul II celebrated Mass in Gdansk in 1987 and Sopot in 1999.

For decades after the war, Kołodziej did not want to talk about the camps. In 1992, the artist suffered a stroke, leaving him partly paralyzed. His doctors encouraged him to paint and draw as therapy. Furthermore, the stroke reminded Kołodziej of his mortality; thus he decided to leave a testimony of the horrors he had experienced.

Until his death in 2009, Kołodziej drew and painted more than 260 works depicting the horrific conditions in the camps. He began drawing in 1993 and donated his exhibit to the Franciscan convent in Harmeze four years later. While at Auschwitz, Kołodziej worked as a forced laborer in Harmeze. He met Franciscan Father Maximilian Kolbe, the Polish friar who volunteered to die in a starvation bunker to save another man, and it is possible that St. Maximilian’s ashes were scattered around Harmeze. When he learned that the Polish Franciscans, who did not know that there was a forced-labor camp in Harmeze during the war when they established a community there, had recently built a convent there, he knew it was the perfect place for his art. Harmeze is less than 4 miles from Auschwitz. The Franciscan convent on Franciszkanska Street includes a Japanese garden with a statue of St. Maximilian, one of Kołodziej’s last works. The enormous Negatives of Memory: Labyrinths exhibit is housed in the convent basement.

The extreme violence of Nazi Germany led many victims to question their belief in God. For Kołodziej, however, faith helped him to survive the ninth circle of Hitler’s inferno, to adapt a Dante reference. One of the first things visitors see upon entering the exhibit is Kołodziej’s drawing referring to Matthias Grünewald’s painting The Crucifixion.

“This is Kołodziej’s way of responding to the question of where God was in Auschwitz,” Conventual Franciscan Father Piotr Cuber, of the order that operates the Harmeze convent, explained during a recent visit. “Kołodziej believed that Christ was there with the suffering prisoners.”

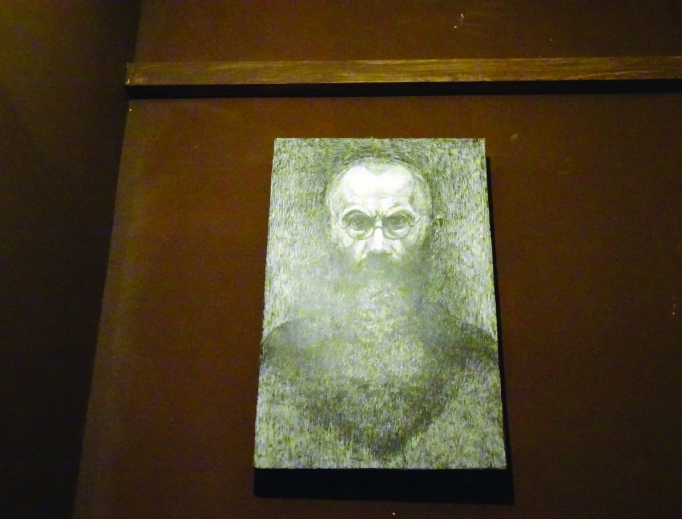

Kołodziej’s works depicting camp life are done in black and white and are occasionally juxtaposed with Kołodziej’s set designs, relics of a happier time in his life, which marks the contrast between death and life. Kołodziej himself is often depicted as an old man dragging his young self, symbolizing the burden of his wartime trauma.

Art enthusiasts will find in Negatives of Memory: Labyrinths many references to canonical works of art. Apart from Grünewald, there are allusions to Albrecht Dürer’s drawing style, Hieronymus Bosch’s visions of hell, and Hans Memling’s vision of the Final Judgment.

“What most people remember is skulls and eyes,” Father Cuber said, referring to how the prisoners depicted in Kołodziej’s work have distended skulls and hollow, frightened eyes, tangible effects of the years of hunger and terror experienced in the camps.

Kołodziej’s depictions often contain metaphorical imagery that feels painfully real. The kapos — prisoners, frequently common criminals, who often cruelly oversaw their fellow inmates’ work — are depicted as fanged beasts.

In a depiction of prisoners’ dreams, lice, the typhus-carrying insects that tormented so many inmates, have cruel, demonic faces. The depictions of the chimneys of Birkenau belch out smoke made of human faces.

Kołodziej’s work is deeply Christian. In different images, Christ and St. Maximilian offer succor to camp victims. In one, three inmates are shown as hanging crucified, a reference to the Place of the Skull. In another, Christ takes down a prisoner from a pole (concentration-camp inmates were tied to poles and tortured). Many scenes are influenced by the Bible. Some refer to the Final Judgment in Revelation. St. Maximilian Kolbe appears in 46 drawings. Kołodziej’s fascination with Kolbe also suggests that God was present in the humanity of such heroic, holy individuals. Kołodziej himself survived the camp thanks to human kindness and divine Providence.

One day, he shared his soup with a fellow inmate, Tadeusz Szymanski. The latter later worked as a camp writer. Stumbling upon the list of prisoners intended to be shot, he saw Kołodziej’s name and secretly removed it.

Photographic Plates of Memory is an art installation. The part of the exhibit dedicated to Jewish victims has rocks in front of it (Jews place rocks, rather than flowers, on burial sites) and a Jewish prayer shawl. Meanwhile, upon exiting the exhibit visitors see a drawing with a piece of cracked glass over it. This is intentional: Kołodziej wanted visitors to stomp on the glass to make sure that what they have seen leaves an impact.

“Last year, we had 8,000 visitors from 30 countries visit us,” Father Cuber reported. “Many tell us that the exhibit left a bigger impact on them than Auschwitz itself. The former camp is like a theater set without the actors, but Kołodziej’s art adds a human dimension.”

Kołodziej’s exhibit is a moving tribute to the millions of victims of the Third Reich and a reminder that the crucified Christ does not abandon those who suffer most and is present in the rare acts of humanity amid human depravity for which St. Maximilian is well-known.

Filip Mazurczak writes from Krakow, Poland.

- Keywords:

- filip mazurczak

- holocaust

- st. maximilian kolbe