Seminarian Who Drowned While Saving Kayaker ‘Lived and Died a Priestly Life’

Hero seminarian’s ‘bucket list’ said: ‘I want to save someone’s life.’

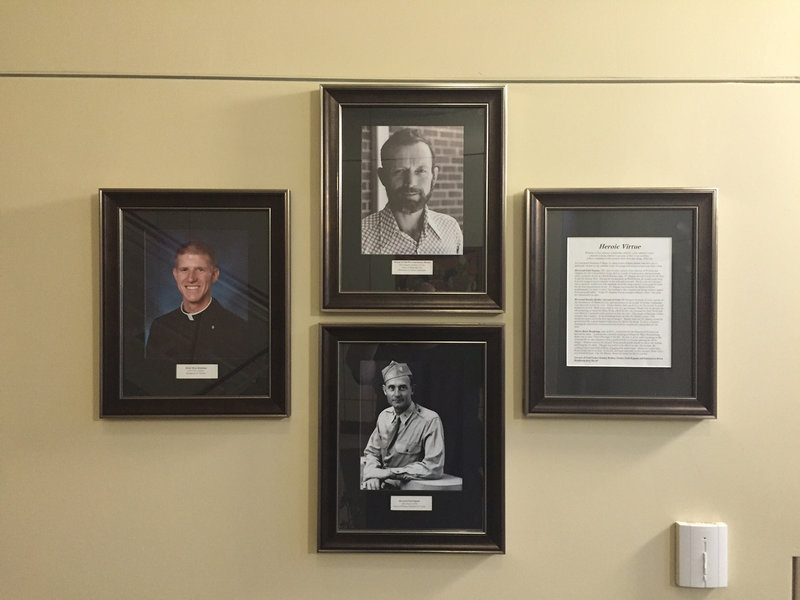

As students checked into Conception College Seminary near Maryville, Missouri, this fall, they walked past a new “wall of heroes” — three large, framed photos of seminary alumni who died for others.

One is Father Stanley Rother, who was gunned down by a death squad in 1981 Guatemala. Another is Father Emil Kapaun, in the Army chaplain’s uniform that brought him to his heroic death in 1951 Korea.

The third is Mr. Brian Bergkamp.

At first, the 24-year-old grinning face of the seminarian doesn’t seem to fit in with the two seasoned priests.

Then you hear how he died last summer in Wichita, Kansas.

“On July 9, 2016, while kayaking on the Arkansas River, the turbulent waters grabbed hold of a woman, placing her life in danger,” wrote the seminary’s president-rector, Benedictine Father Brendan Moss. “Without concern for himself, Brian abandoned his kayak to rescue the woman and bring her to safety.”

His words read like a citation for bravery: “Though successful in his efforts to save this woman, the rushing waters took hold of Brian, dragging him underwater. About two weeks later, Brian’s body was recovered. In his life, and most especially in this moment, Brian was a true friend of Jesus. Like the Master, Brian laid down his life for another. He was a doer of the word and not a hearer only.”

“Unconcerned about himself.” “Living for others.” “Faithful.” This is the description I would hear from his family, friends and fellow seminarians — and in Bergkamp’s own haunting words that have taken on new meaning after his death.

Kansas Farm Boy

“One thing we want to say up front is the fact that Brian was an ordinary child and young adult,” his mother, Teresa, told me.

“He wasn’t perfect — he had struggles and faults, like the rest of us. He had a desire to serve God and help others, and that is why he chose to become a priest. But God had other plans.”

You get a taste of who Brian Bergkamp was from his Facebook posts. A passionate pro-lifer, his last public post before he died celebrates Kansas defunding Planned Parenthood. Farther down on the page, you find his faith and sense of humor.

He liked sharing memes. One said: “The Church needs to get with the times … said every failed empire for 2,000 years.” Another celebrates his upbringing: “If you sat here as a kid,” it says over a picture of a tractor seat, “you had a good childhood.”

Bergkamp had a good childhood. He was born on Jan. 13, 1992, the third child of seven born to Ned and Teresa Bergkamp of Garden Plain, Kansas, population: 773. He grew up in a small house with one bathroom. “It was kind of crazy,” said Teresa, “a real juggling act.”

“All the children worked outside on the farm,” she said. “Up until 11 years ago, we always dairied. They always got up on weekend mornings with their dad to go milking at 5 in the morning.”

The priesthood loomed large in their third child’s mind. “I think Brian first felt called to the priesthood as a young child, so from early on,” his brother, Deacon Andrew Bergkamp, said, "he always took his faith seriously.”

But he never took himself too seriously.

“As a child, he was always bright-eyed and full of smiles,” his mother told me. “He was very talkative. He got in trouble in kindergarten. I didn’t know it until the first conference. He was talking too much! He was outgoing, very welcoming. He would make almost anyone feel at ease.”

Bergkamp’s own memories of his vocation are about talking to others about it.

“I remember in second grade, my close friend and I would argue back and forth on who would be a priest first,” he wrote for the Diocese of Wichita website. “And as time would tell, it looks like we will both be priests at the same time, for we are now both entering the seminary.”

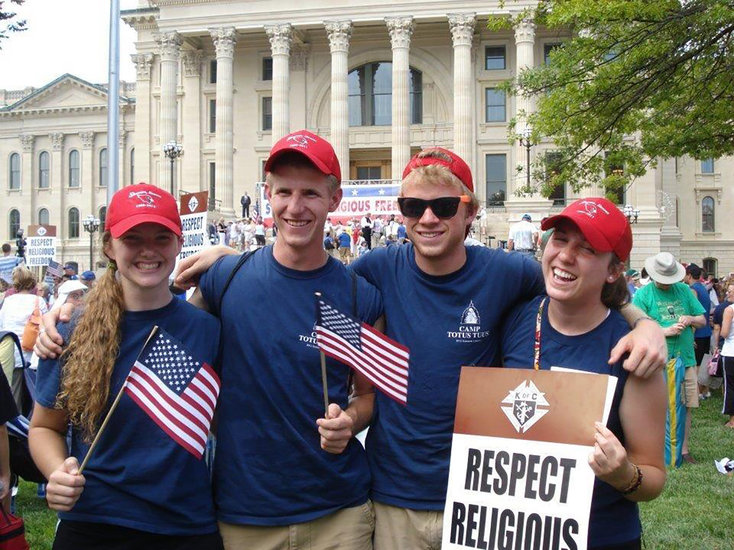

I asked Teresa: “How is it that two of your sons went to seminary? What did you do?” She credited the local parish, where the boys served at the altar, specifying several priests: Fathers David Linnebur, John Reinkemeyer, Ivan Eck and Sam Pinkerton. It also helped that, in high school, Bergkamp went to Steubenville Youth Conferences every summer and the March for Life in Washington every winter.

She said that they, as parents, didn’t push the idea of religious vocations; but the family prayed together every night at 8:30, before 9 o’clock bed time, and always included prayers “for vocations and for the poor souls in purgatory.”

“Part of it is, I don’t even know,” she added. “Deacon Andrew will be the first-ever ordained from our parish, which is 100 years old. But then, all of the sudden, we had four vocations. It is, in part, our diocese. Wichita has a lot of Eucharistic adoration. Our parish doesn’t have perpetual, but we have it 24 hours once a week.”

Freshman Memories

After high school, Bergkamp headed to Atchison, Kansas.

“I think Brian knew he would probably enter seminary, but wanted to experience a taste of regular college life, so he began his education at Benedictine College,” said Teresa. “He knew it was a good, solid Catholic college.”

“I had ‘Logic and Nature’ with him,” said Matthew Nordhus, referring to a required philosophy course at the college. “We had a lot of good friends in that class, but it was hard. We started out reading Plato’s Republic together.”

When they weren’t puzzling out the classics, Nordhus said his “friend group” would swing dance and do “typical freshman things.” He remembers climbing the “Signing Tower” at Benedictine College. It is a college tradition to squeeze through a wall in the old abbey, wriggle to the top and write one’s name up high in the beams. “Brian helped get us up to the top level,” Nordhus said, sharing the photos to prove it.

Another Benedictine friend, Anne Jenkins, remembered Bergkamp as someone who could always be relied on for help.

On one occasion, she and a friend were returning from Easter break through a torrential downpour.

“Our windshield wipers malfunctioned and ended up flying off of the car on the freeway near Topeka,” she said. They couldn’t see and had to pull over. She called Bergkamp, who was also returning to campus. “He was 30 minutes past Topeka already, but told us that he would turn around and come get us,” she said. “That’s just who he was — someone who was willing to help anyone who asked.”

When the time neared to depart for the summer, Bergkamp told the group he was transferring to the seminary. They had a “last supper” for him in the kitchen of a freshman dorm.

“It was the worst meal we had all year,” Nordhus said. “We weren’t good cooks. And we had sparkling grape juice because no one was 21.”

Nicole Walz, of Minnesota, was at the meal, too. She said the group ceremoniously split up a bean that someone had grown for biology class, and each ate a sliver of it.

Then followed finals week, when students begin to disperse, withdraw into studies and then depart.

With no one around, “I had free time, so I texted Brian to see what he was doing,” said Nordhus. “He was out in Abbeyland and said to come on out.”

Nordhus walked out past the monks’ cemetery and the outdoor Stations of the Cross to the vast wooded property adjacent to campus owned by St. Benedict’s Abbey. He found Bergkamp there, hiding the sparkling-grape-juice bottle — only now it had a note in it.

“This was kind of his good-bye,” Nordhus said. “He wanted to leave some notes and encouraging things and, being the guy that he is, kind of have some fun. So I helped him hide the bottle.”

Bergkamp hid five bottles in all and waited until fall to send his friends clues to find them.

Jenkins remembers the process of tracking down the bottles — sometimes with extra hints from Bergkamp — and finding the farewell letter.

Vocations directors warn seminarians that the devil works hard on young men who are headed to the priesthood. Bergkamp was no exception.

“The more I think about it, Satan is only doing this because he can see the true potential I have as a priest — the havoc I will bring to Satan and his desires and the joy and peace I can give the Catholic Church,” wrote Bergkamp.

His next words only make sense because of his death: “At this point in my life, I believe I will become much more than just a priest,” he said, “that I am called to something higher, enabling me to reach out to thousands of Catholics.”

Finding Peace in Seminary

Andrew Gaffney, a seminarian of the Archdiocese of Kansas City, Kansas, remembers that Bergkamp embraced the student-led project of rebuilding an ancient Marian grotto that was a short hike from Conception Seminary College.

“Everyone kind of finds a special place on campus, a place where they can find peace,” said Gaffney. “Mine is the grotto, and his was, too.”

Bergkamp rebuilt the fence that separates the grotto from the farm beyond it.

Wichita seminarian James Schibi also got to know Bergkamp at this time in his life. “He was never about himself, always looking to do something for others,” Schibi told The Wichita Eagle.

“He was a really an inspiration to us in the seminary and really a man that you want to model yourself after,” he said, “a man of great faith.”

After finishing at Conception Seminary College, Bergkamp started at Mount St. Mary’s Seminary in Emmitsburg, Maryland, where he would have entered his third year of theology studies this fall.

“In the last couple of years,” said Teresa, “Brian would sometimes skip meals at the Mount to save up some of his cafeteria dollars and buy things in the cafeteria ‘store’ for us … headbands and nail polish for his younger sisters and special food items we didn’t ordinarily buy or things he knew we could use. It was fun to see what he would come home with.”

His Last Act

Bergkamp “loved God above all else and lived his life according to the sacrifice of the cross,” said Jenkins. She re-read notes from him after he died and was struck by one: In it, he wrote a “bucket list” of things he intended to do before he died.

“I want to save someone’s life by physically doing something, like a hero,” Bergkamp wrote.

“Even if he didn’t get to do many of the other things on his list, I honestly believe that he valued this one the highest anyway,” she said.

Wichita Fire Battalion Chief Frank Buck described the part of the Arkansas River where Bergkamp died.

“The spillway underneath the bridge here at 21st Street is about a foot and a half to two-foot drop off,” he told The Wichita Eagle. This creates conditions under the bridge that the paper later called a “drowning machine.”

That is where Bergkamp saw the back of the woman’s kayak get sucked into the water, throwing her into the river without a life jacket. He threw her a life jacket and got her to safety.

“He saw somebody in trouble, and he knew he had to do something — and he did,” the fire chief said. “He ended up saving her life.”

As Wichita Bishop Carl Kemme said at his funeral, “He may not have been a priest, but he lived and died a most priestly life.”

Deacon Bergkamp, his brother, preached at his funeral and said that those who loved Brian were devastated by his death, but that they were “not seeking answers because, one, they wouldn’t make sense this side of heaven; and, two, they wouldn’t remove the sadness that we feel. But we turn to God because he has revealed that he loves us more than we can comprehend.”

Gaffney told me that seminarians who reached out to comfort the family found that they were the ones who received consolation.

When I asked Teresa about her son’s heroic death, she talked about the woman he saved. “I’m sure it’s hard for her,” she said. “We are planning on calling her up to see how she is doing. She’s teaching and starting a new position.”

Nicole Walz, a friend from college, told me about the last conversation she had with Bergkamp, shortly before he died. “He told me he wouldn’t be spending the Fourth of July with his family because he’s spending the summer volunteering with other seminarians at the Lord’s Diner, a soup kitchen that feeds about 2,500 people a day,” she said. “He lived just as he died, putting another person’s life before his own, giving his life just as Jesus did.”

As for Bergkamp, his life didn’t really go very far from where he planned. In his farewell note to his Benedictine College friends, he said he didn’t know if he would ever be ordained or not, but he wanted to give God a chance.

“Either way, after all this, my life is simply on a short journey to the everlasting kingdom of God,” he wrote. “My time here on earth is short, and so I must make the best of it.”

And that is exactly what he did.

Tom Hoopes is writer in residence at Benedictine College.

His new book is What Pope Francis Really Said.