Vatican Conference on Catholic Church in China Reflects the Vatican’s Compromises

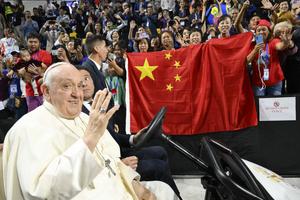

ANALYSIS: The May 21 gathering shows that Pope Francis remains committed to pursuing closer ties with the People’s Republic.

VATICAN CITY — The Holy See and the People’s Republic of China have never had formal diplomatic relations. But under Pope Francis, the two have come closer together than at any time since the communist revolution of 1949, most notably with a 2018 agreement that gives both sides a say in the appointment of Catholic bishops.

A Vatican conference May 21 on the history of the Church in China was the latest sign of this rapprochement — and a prominent illustration of the compromises that the Church has made in the process.

Speakers at the conference included Cardinal Pietro Parolin, the Vatican secretary of state, and Cardinal Luis Antonio Tagle, acting head of the Vatican’s Dicastery for Evangelization. Pope Francis greeted the gathering in a short video. But the most notable speech was by Bishop Joseph Shen Bin of Shanghai.

Bishop Shen Bin is chairman of the Chinese Catholic Bishops’ Conference, a government-controlled body not recognized by the Holy See. Last year, Chinese authorities transferred him to his current post in Shanghai without consulting the Vatican, which accepted the move under protest.

The bishop is thus the leading prelate in the government-controlled portion of the Church in China, often referred to as the official Church to distinguish it from the so-called underground Church, made up of Catholics who resist government control. The total number of Catholics in China is estimated at around 10 million.

Like the other speakers at the Vatican conference, Bishop Shen Bin spoke about the legacy of the 1924 Council of Shanghai, which encouraged the Church in China, led at that time by foreign missionaries, to develop an indigenous clergy and otherwise distance itself from the colonial Western powers that had long supported it, so that it would no longer be considered a foreign religion.

The bishop said that the Church in China today should accordingly follow a policy of “sinicization” to make Catholicism more Chinese, for instance by adopting traditional local forms of religious art, architecture and music.

Sinicization is the name of a campaign launched by China’s leader Xi Jinping to transform all of the country’s society, including religion, by aligning it not only with Chinese culture but with the ideology of the country’s Communist Party.

Bishop Shen Bin has acknowledged this. In an interview with a state news agency last year, the bishop said that sinicization “should use the core socialist values as guidance to provide a creative interpretation of theological classics and religious doctrines that aligns with the requirements of contemporary China’s development and progress, as well as with China’s splendid traditional culture.”

The bishop downplayed that side of sinicization in his speech at the Vatican this week. He noted there that the constitution of the bishops’ conference states that the body's mission “is to uphold the faith, preach the Gospel, and promote the holy church based on the Bible and tradition, adhering to the spirit of the universal and apostolic Catholic Church and the Second Vatican Council.” He did not quote the next sentence of the same document, which states that the bishops’ conference “supports the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party, the socialist system, and adheres to the principles of independence and self-governance in political, economic and church affairs.”

Such a combination of principles would seem to sit uneasily, to say the least, with Pope Francis’ oft-stated aversion to ideologies, especially when they substitute for religious faith. “All ideology is bad, whether it is from the right, the center, or the left,” the Pope said to CBS in an interview broadcast this week.

Yet the agreement with Beijing on the appointment of bishops has bolstered the position of the official church in China, and thus its program of sinicization, since the civil authorities point to it as a sign of papal approval.

The year after the agreement, the Vatican encouraged underground clergy to register with the civil authorities. Archbishop Paul Gallagher, the Vatican Secretary for Relations with States, told EWTN last year that the agreement “was always going to be used by the Chinese party to bring greater pressure on the Catholic community, particularly on the so-called underground Church.”

So why have Pope Francis and his advisers concluded that their overture to China is worth such compromises on religious freedom?

A key factor is clearly the Pope’s desire to reduce the danger of schism, or a permanent split in the Church, by unifying the Catholic hierarchy in China. Only nine bishops have been named under the current agreement, and some 40 dioceses in China are still lacking a bishop, but at least the government has promised not to appoint bishops without approval of the pope.

“The aim is the unity of the Church,” Cardinal Parolin said of the deal in 2020. “All the bishops in China are in communion with the pope. There are no more illegitimate bishops.”

Unity was equally a concern for St. John Paul II and Pope Benedict XVI, who cooperated with Beijing on the appointment of bishops in China even in the absence of a formal agreement. But Pope Francis’ China policy also reflects other priorities of his pontificate.

One of these is the Pope’s emphasis on dialogue with the non-Catholic world. In his speech to the Vatican conference, Cardinal Tagle mentioned a prominent example of such outreach, the Abu Dhabi declaration on Human Fraternity, which the Pope signed with the Muslim leader Sheikh Ahmed el-Tayeb in 2019. Another example is Pope Francis’ support for the DIALOP transversal dialogue project, which the official Vatican News outlet has described as “aimed at formulating a common social ethic … with an integral ecology between the Social Doctrine of the Church and Marxist social critique at its core.”

Yet another factor at play in his dealing with China is Pope Francis’ distinctively multipolar geopolitical outlook, unbound by deference to the priorities of a U.S.-led West, which inspires the Pope to engage with the rising Chinese superpower. That approach is also evident in the Pope’s stand on the war in Ukraine, which he has suggested was provoked by NATO “barking at Russia’s gate.”

This week’s conference shows that Pope Francis remains committed to pursuing closer ties with the PRC. The agreement on the appointment of bishops expires this fall and Cardinal Parolin told reporters on the sidelines of the conference that both parties to the deal were interested in renewing it. He said the Vatican still hoped to establish some kind of permanent representative office in the country, even if well short of an embassy.

Studying the 1924 Council of Shanghai has inspired the cardinal to have hope as well as patience in his dealings with China, he said: “The seeds that are cast on the ground, even if they don’t seem to yield anything immediately, germinate in the end and there is always something to harvest.”