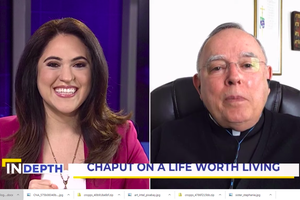

Laity Are at the Heart of Archbishop Chaput’s Legacy

ANALYSIS: Collaborators reflect on the legacy of a shepherd with an outsized impact on the Catholic Church in the United States.

Archbishop Charles Chaput of Philadelphia marks his 75th birthday on Sept. 26.

As canon law stipulates, he is expected to tender his resignation to Pope Francis, but whether it is accepted or set aside, the anniversary is a time for his closest collaborators to reflect on the legacy of the first Native American to become an archbishop — a shepherd with an outsized impact on the Catholic Church in the United States who took “risks” to empower lay apostolates.

“I learned a lot from him about the need for getting solid laypeople involved in the work of the Church and giving them the space to take a vision of the New Evangelization and move forward on it,” said Archbishop Samuel Aquila of Denver, who had served as the founding rector of St. John Vianney Theological Seminary, which opened early in Archbishop Chaput’s tenure in the Rocky Mountain State.

Cristine Barba, a Philadelphia Catholic who in 2014 founded her own apostolate, The Culture Project, inspired by a desire to share Catholic teaching on human dignity and chastity with young people, used similar language to describe the archbishop’s gift for nurturing new apostolates.

“He gives firm, clear guidance and leadership, and then gives space,” Barba told the Register. “He pushed me, giving me the confidence to launch The Culture Project. The longest I waited for him to respond to an email was a day.”

During his 31 years as a bishop, Archbishop Chaput, ordained to the priesthood in the Capuchin Franciscan order, backed dynamic lay apostolates like the Fellowship of Catholic University Students (FOCUS), the Augustine Institute and Endow. Aides and lay collaborators describe him as a talent spotter and risk taker who is accessible and generous with his guidance and contacts, but will withdraw support if he loses confidence in a project.

Engages the Laity

“He is entirely a bishop of the Second Vatican Council and very interested in engaging the laity,” said Sean Innerst, who served as a director of religious education during his first episcopal appointment as bishop of Rapid City, South Dakota, from 1988 to 1997.

Bishop Chaput was “young and energetic” and had already served as a Capuchin provincial superior before his 40th birthday. Innerst liked his episcopal motto: “As Christ Loved the Church” (Ephesians 5:25).

“His apostolic agenda … was not inspired by a hidebound conservativism, but a real Catholic traditionalism that sees the necessity to change with the times, but not change the Gospel,” said Innerst, who recalled the excitement he felt as the bishop encouraged lay members of the chancery to undertake new initiatives.

Raised in Kansas and a graduate of Catholic schools, Archbishop Chaput is also a member of the Potawatomi people. In Rapid City, he worked to strengthen ties between Native American Catholics and the diocese, including those on the five reservations within its borders, and established the Office of Native Concerns, now called the Office of Native Ministry.

‘Vocations Magnet’

Further, Bishop Chaput bolstered and reformed catechetical programs in local Catholic schools and parishes and modernized diocesan fundraising to support the burgeoning ministries, including the first diocesan high school.

“Vocations doubled in Rapid City from one year to the next,” Innerst reported. “He is a vocations magnet” by taking personal interest in young people.

After his appointment as archbishop of Denver in 1997, Archbishop Chaput recruited Innerst and other trusted lay leaders to move to Colorado. Their fresh initiatives tapped into the renewed sense of hope and passion for evangelization generated by World Youth Day in 1993 and the presence of Pope John Paul II.

Curtis Martin, who would become the founder of FOCUS, moved to Denver at Archbishop Chaput’s invitation.

The two first met in 1993, when Martin passed through Rapid City on his way to World Youth Day, and they bonded over group hikes, racquetball and conversations about the younger Catholic’s dream of assembling a team of missionaries to evangelize college students.

“He told me, ‘I can support you and encourage you, but you do it. You should never lean on a bishop. We don’t live forever and can get replaced,’” Martin told the Register.

The archbishop introduced Martin to “dozens of bishops and benefactors. Those early contacts became allies and helped FOCUS grow,” said Martin.

A similar dynamic played out during the launch of the Augustine Institute, established to provide strong intellectual and apostolic formation for laypeople serving the Church.

The archbishop and his circle of collaborators believed that new cultural challenges required “a high level of formation” for the faithful, explained Jonathan Reyes, who also moved to Denver to work on the project and now serves as assistant general secretary for integral human development at the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops.

Appointed to Philadelphia

In 2011, Archbishop Chaput was appointed to lead the Philadelphia Archdiocese and moved to a local Church with a broader and deeper institutional footprint. But his new archdiocese had been badly damaged by two explosive grand jury reports detailing allegations of clergy abuse against minors in 2005 and 2011.

The second report led to the conviction of Msgr. William Lynn, former archdiocesan vicar for clergy, on charges of child endangerment. Msgr. Lynn’s conviction was overturned in 2016 by the state Supreme Court, and a retrial is expected later this year.

A recent archdiocesan study suggested that “the clergy sexual-abuse crisis and the closure of Catholic churches through parish mergers” helped fuel the steady decline in local Sunday Mass attendance to just under 200,000 churchgoers in 218 parishes, a 52% drop since 1990.

“Denver had been ripe for growth, and all the fundamentals were aligned for that,” said one of Archbishop Chaput’s former Colorado staff. “Philadelphia was different. He was a fireman for the first five years: The financial, legal and political problems were crushing.”

Archbishop Chaput met with abuse victims and oversaw a thorough review of allegations against local priests that often dated back many decades.

During his eight years in Philadelphia, he would face criticism from victims’ groups angered by his opposition to proposed legislation that would retroactively lift the statute of limitations for civil lawsuits in abuse cases.

But in 2018, he established an Independent Reconciliation and Reparations Program (IRRP) designed to “compensate all victims but especially those whose claims are currently time barred from civil lawsuits.”

Internal Investigation

That same year, the archdiocese began an internal investigation into allegations of sexual harassment against a former Philadelphia seminarian that reportedly occurred during the 2010-2011 academic year.

“The AOI [Archdiocesan Office of Investigations] confirmed the allegations of sexual harassment were reported to seminary leadership and responded to in a timely and appropriate manner. The offending seminarian left the seminary,” reported Bishop Timothy Senior, the rector of St. Charles Borromeo Seminary, in a letter to the seminary community.

Meanwhile, Archbishop Chaput tackled the archdiocese’s $350-million deficit and gradually brought it under control, in part, by reducing staff, balancing budgets and selling property, including the archbishop’s mansion.

Along the way, he looked for opportunities to hire lay Catholics for open staff positions and gave more responsibility to the archdiocesan pastoral council.

Cristina Barba, a former chairwoman of the pastoral council, was impressed with his handling of the group’s quarterly daylong meetings.

“He asked the presenters, including lawyers and finance people, to be transparent with us,” she said.

“Later, he would run through the day’s agenda … and sometimes he would rethink his ideas based on our response. I was so impressed with his humility,” said Barba.

Barba also got help from the archbishop after sharing her plans for launching her own The Culture Project apostolate, which she described as “a movement of lay young adult Catholics that go on mission and speak about chastity, human dignity and a life of virtue in the Church.”

“He invested in me and was available for questions and guidance. He didn’t overpromise, but ended up delivering so much more,” she reported, noting that her group now serves 35 dioceses after just five years.

Cultural Analyst

That gift for empowering the laity to initiate their own projects will remain a critical part of Archbishop Chaput’s legacy. But his supporters also point to the books and articles that have brought his Catholic vision of life and incisive cultural analysis to a greater number of Catholics and Christians, shoring up the confidence of religious believers who fear they have been pushed to the sidelines in mainstream America.

“Hailing from a Native American family on one side, he has a unique claim to a voice that speaks not only about America over the last 240 years, but also the America that predated the Revolution,” said Bill Barry, who served as publisher of Doubleday Religion and worked on Archbishop Chaput’s 2008 best-seller, Render Unto Caesar: Serving the Nation by Living Our Catholic Beliefs in Political Life, and as literary agent for Strangers in a Strange Land: Living the Catholic Faith in a Post-Christian World (2017).

“He has been able to dissect what became the great American experiment and to hold its current iteration to the original spark that gave life to that revolution,” said Barry, noting that Render Unto Caesar was published four years before the Hobby Lobby case and the U.S. bishops challenged the Health and Human Services’ contraceptive mandate in court.

Archbishop Chaput has also become a trusted supporter of the Alliance Defending Freedom and the Becket law group, a pair of organizations that provide legal representation to plaintiffs in religious-freedom cases.

William Mumma, the CEO and chairman of Becket, which represented the EWTN Global Catholic Network, the Register’s parent company, in its suit against the HHS mandate, suggested that Archbishop Chaput got involved in this work precisely because of his close contact with lay leaders who witnessed anti-religious bigotry firsthand.

Archbishop Chaput is “a bishop who conceives of the Church in its fullest sense,” said Mumma. If lay Catholics aren’t free to exercise their faith, “then the Church isn’t free.”

Archbishop Chaput’s membership on numerous boards, including EWTN’s and Becket’s, and his past appointment to the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom (2003-2006) has added to his influence. However, some Church leaders and commentators contend that his advocacy of particular policies is too closely associated with a conservative ideology, increasing the danger that his activism will be manipulated for partisan gain and damage the Church’s moral credibility.

Such concerns about his activities have circulated in the Vatican. And when Archbishop Carlo Viganò, the former apostolic nuncio to the United States, issued his incendiary 2018 “testimony” that accused Pope Francis of ignoring allegations of sexual misconduct against the now-disgraced former Cardinal Theodore McCarrick, the nuncio’s statement also suggested that Francis did not approve of Archbishop Chaput’s high-profile role in the U.S. culture wars.

This particular claim has not been verified. But Church watchers say it may help explain why the Philadelphia archbishop was not made a cardinal like his predecessors. Philadelphia has traditionally been considered a cardinalatianal see.

Amoris Laetitia

On the other hand, Archbishop Chaput’s supporters are quick to point to his election in 2015 to the permanent council of the Synod of Bishops. He is the only North America prelate to receive this particular honor, and that suggests his striking candor and clarity on sensitive issues roiling the Church have won the respect of many peers throughout the world.

In 2016, for example, he stood his ground after Cardinal-elect Kevin Farrell, prefect of the Dicastery for the Laity, publicly questioned his approval of archdiocesan guidelines for implementing Pope Francis’ controversial apostolic exhortation Amoris Laetitia, which critics contend softens Church teaching on reception of Holy Communion for divorced-and-remarried Catholics. Archbishop Chaput’s guidelines, in keeping with long-standing Church teaching, did not allow any pastoral flexibility for the divorced and civilly remarried to receive Communion unless they lived as “brother and sister” or received an annulment.

“The Church cannot contradict or circumvent Scripture and her own magisterium without invalidating her mission,” said Archbishop Chaput in his published response to a Catholic News Service query. “The words of Jesus himself are very direct and radical on the matter of divorce.”

But if Archbishop Chaput has become a polarizing figure for some Catholics, especially those who believe that a correct interpretation of the Second Vatican Council justifies a rupture in the continuity of Tradition, he remains a trusted shepherd to those who have watched the fruits of his apostolate multiply.

Vital Connection

As Archbishop Aquila looks back on his predecessor’s legacy, he sees a vital connection between the steady supply of priestly vocations and the ongoing presence of vibrant lay apostolates, especially FOCUS missionaries working in the five universities in the area.

This month, as Denver’s St. John Vianney Theological Seminary marks its 20th anniversary, it is at capacity, with 115 men in formation. Fifty-three of them are from Denver, which also has additional men studying in Rome and other seminaries.

Curtis Martin, for his part, continues to be inspired by Archbishop Chaput’s gift for fellowship and for attending to young Catholics searching for their place in the world and in the Church.

“He would ask me out to lunch, and there would be a random guy, maybe someone thinking about converting to Catholicism or returning to the Church,” said Martin.

“You were expected to take them under your wing and befriend them. So much that is wrong with the Church would be restored if we understood that friendship is critical.”

Joan Frawley Desmond is a Register senior editor.