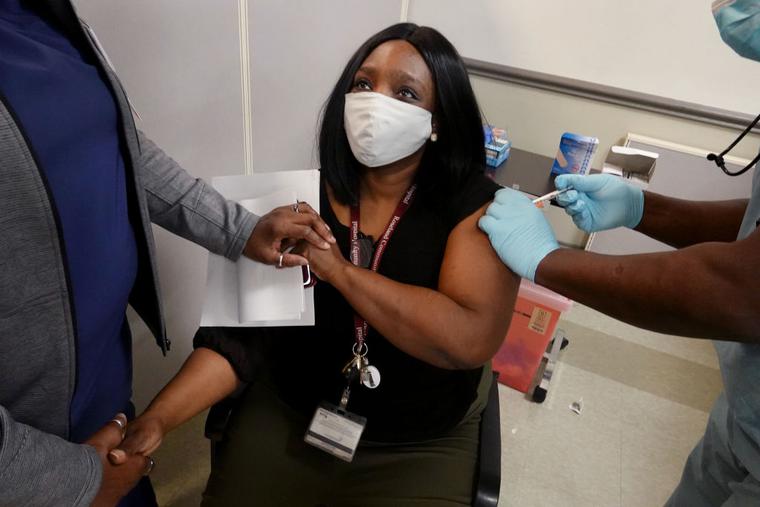

As COVID-19 Vaccinations Begin, Ethical Issues Remain in Play

Along with the controversy over use of vaccines with connections to abortion-derived tissues, other key questions include the right to refuse vaccines, mandatory vaccination, and distributing the vaccines fairly.

As a pair of COVID-19 vaccines become available in the United States, Catholics are receiving assurances from their bishops that they can, and even should, accept them, despite some degree of association with morally compromised means of production.

But the U.S. bishops are also stressing the continuing need to push for alternatives with no such association, and other questions are arising about the right to refuse them and about their fair distribution.

The U.S. bishops in a Dec. 14 statement have told Catholics that they can accept the newly available vaccines from Pfizer and Moderna despite their remote connection to morally compromised fetal cell lines derived from a baby aborted decades ago as long as they register their objection to the use of aborted children in scientific research and in medical treatments.

In the case of a third new vaccine produced by AstraZeneca, which has a much more direct association with an abortion-derived cell line, the bishops advised that “it should be avoided if alternatives are available.” That vaccine has not yet been approved for use in the U.S.

Not everyone concurs with the Dec. 14 statement’s overall assessment. Even before the bishops issued that statement, Bishop Joseph Strickland of Tyler, Texas, in a letter had urged rejection of “any vaccine that uses the remains of aborted children in research, testing, development or production.”

Bishop Strickland stood by that in a Dec. 15 interview, saying he wants to wait for an ethically produced vaccine.

“I know I’m in the minority, but I think we’ve all got to really think about that,” he said.

The U.S. bishops concluded their Dec. 14 statement with a pointed reminder about the moral obligation to campaign vigorously for alternatives to medical research and production that involve the utilization of abortion-derived human tissues, in all contexts where that currently is taking place, including in the case of the new COVID-19 vaccines.

“For our part, we bishops and all Catholics and men and women of goodwill must continue to do what we can to ensure the development, production, and distribution of a COVID-19 vaccine without any connection to abortion and to help change what has become the standard practice in much medical research, a practice in which certain morally compromised cell lines are routinely used as a matter of course, with no consideration of the moral question concerning the origins of those cell lines.”

The Vatican provided a similar assessment to that of the U.S. bishops, in a Dec. 21 doctrinal note issued by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. While the note advised that it is “morally acceptable” to take the new vaccines “when ethically irreproachable COVID-19 vaccines are not available,” it affirmed Catholics can decline to take them on grounds of conscience and that pharmaceutical companies should be lobbied to manufacture and distribute vaccines that are completely acceptable ethically.

Prudential Judgments

Even as they have advocated for development of a vaccine without a link to abortion, the bishops said in their statement that they believe the reasons to accept the available vaccines are sufficiently serious to justify their use, adding that being vaccinated is an act of charity toward others and part of one’s moral responsibility for the common good.

“If one were to refuse vaccination,” the bishops said in a footnote to their statement, “one would have a moral responsibility to undertake all the precautions necessary to ensure that one does not become a carrier of the disease to others, precautions which may include some form of self-isolation.”

Still, Father Tad Pacholczyk, director of education for the National Catholic Bioethics Center, said each person must evaluate his or her individual situation and make a good prudential judgment regarding benefits and burdens when accepting a COVID-19 vaccine. Health-care workers, the elderly and other vulnerable populations should consider the benefits closely, he told the Register. Meanwhile, for younger people with low chances of detrimental outcomes, there may be less urgency, especially if they do not have contact with those who are more vulnerable.

“People can decide against receiving vaccines for many reasons,” Father Pacholczyk said. “Some people may have allergies to ingredients in a vaccine or may have compromised immune function. Some may decline a vaccine out of concern that inadequate testing has occurred. But we should scrutinize our own reasons to be sure they are based on correct information.”

He added, “We are called to be attentive to our neighbor and to the common good, so when a new, highly communicable disease appears, we should respond appropriately and prudently. We will need to consider what to do to protect our neighbor, whether through quarantines when we suspect we have been exposed, or through isolation if we discover we are infected, or through the use of personal protective equipment or the potential reception of a vaccine.”

Doctors’ Perspectives

Dr. Paul Cieslak, an infectious-disease physician, public-health practitioner and member of the Catholic Medical Association, said he will be taking the vaccine as soon as he can get it.

Cieslak, who is the medical director for communicable diseases and immunizations for the Oregon Health Authority, said that his hunch is that most health-care workers will want to receive it, given the threat of COVID-19 and the effectiveness of the vaccine.

Dr. Melissa Murphy, chief of surgery at Kent Hospital in Warwick, Rhode Island, said she plans to take the vaccine, which is being offered but not mandated at her facility. The Catholic doctor has cared for patients with COVID-19 and said that, currently, nearly half the patients admitted to her hospital have a COVID diagnosis.

“I do not know of any health-care workers who have declined the vaccine for moral or religious reasons,” she said. “In my surgical department, 97% of our providers have signed up to receive the vaccine. Those who declined did not provide a reason.”

Those who refuse to be vaccinated on religious grounds historically have been protected by laws that require vaccines, according to Stephanie Taub, senior counsel at the First Liberty Institute. Most laws mandating vaccines for schoolchildren, for instance, contain exemptions for religious and other reasons, she told the Register. This is the case in all but five U.S. states: New York, Mississippi, California, West Virginia and Maine.

Taub said she and her colleagues at First Liberty are preparing for possible challenges to COVID-19 vaccine mandates. Much will depend, she said, on how laws are written and how widespread they are. If Joe Biden assumes the presidency Jan. 20, he has said he will urge people to take the vaccine but will not mandate it. However, Taub said such a mandate is more likely to come from a state or locality because states have the general authority to make laws affecting the health and safety of the population.

Employers also could mandate the vaccine, but even if they do, she said, they would be required under federal law to provide religious accommodations.

Ethics of Access

In the near term, however, there is likely not enough of the vaccine to reach everyone who needs it, making prioritizing key. Those most likely to get the vaccine first are the aged, health-care workers and first responders. Some have said priority also needs to be given to homeless people, essential workers and those in places that have been hot spots for infection, such as prisons and universities.

Speaking at his general audience in August, Pope Francis said the vaccine should be available to everyone.

“It would be sad if, for the vaccine for COVID-19, priority were to be given to the richest!” he said. “It would be sad if this vaccine were to become the property of this nation or another, rather than universal and for all.”

Father Pacholczyk said he is not certain that vaccine distribution at the international level will be a significant problem, because many countries are moving quickly to produce their own COVID-19 vaccines. For example, he said, in India, multiple candidates are being developed by several companies, and other companies with successful vaccines are in dialogue with India and other countries. Russia also is making its vaccine available widely, he said.

“There are sure to be bumps along the road of getting an effective vaccine out to everyone who wants to get inoculated, but with strong demand, businesses and markets are likely to respond effectively.”

With limited initial supply of the vaccine, Cieslak said, an effort will be made to protect health-care workers, who are often exposed to the virus and have to be away from work because of isolation or quarantine, leading to staffing shortages. Also at the top of the list, he said, are the elderly, particularly those in skilled-nursing facilities. He told the Register that in the state of Oregon, where he works, if everyone over age 70 had been vaccinated, 76% of deaths from COVID-19 would have been avoided. More than half of the deaths have been in skilled-nursing facilities.

Cieslak said he is especially concerned about getting the vaccine to people of Hispanic ethnicity because, although Hispanic COVID patients have tended to be younger and have a lower case fatality rate, they still have a very high rate of infection.

“I want to put the vaccine where the disease is, and a lot of the disease [among Hispanics] has disproportionate hospitalizations and mortality, and so doesn’t compare with the elderly,” he said.

Murphy said as the vaccine arrived in Rhode Island, each hospital developed an institution-based approach to administration for their health-care workers on the front line. Her hospital system and its leadership developed a phased, comprehensive roll-out plan that called for offering the vaccine first to those in areas with increased exposure to COVID-19 patients, including the emergency department, intensive-care unit, field hospital and other key areas. The ultimate goal, she said, is to make the vaccine available to all hospital providers and staff members.

“Throughout the pandemic, our hospital leadership has worked together with the governor and the department of public health to care for patients with COVID-19,” she said. “Personally, I think it takes this coordinated partnership between health-care leaders and the government to develop a strategy to distribute the vaccine fairly, taking into account those populations most in need.”

Register correspondent Jonathan Liedl contributed to this report. This story was updated Dec. 21 to reflect the CDF guidance issued Dec. 21.

- Keywords:

- covid-19

- vaccinations

- judy roberts