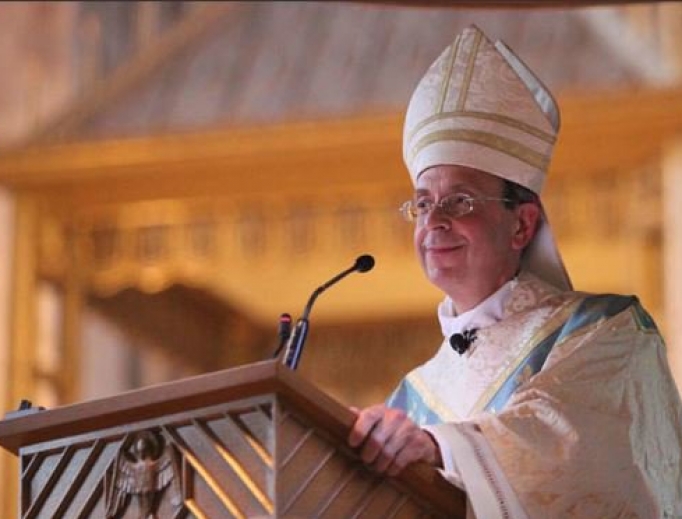

Archbishop Lori on New President, New Challenges for Religious Liberty

In a Register interview, the head of the U.S. bishops’ Ad Hoc Committee on Religious Liberty, discusses the challenges and opportunities for religious liberty with the new Trump administration.

BALTIMORE — For many years, Archbishop William Lori of Baltimore has been at the forefront of the Church’s effort to maintain religious liberty for its Catholic citizenry. Since 2011, he has been the chairman of the U.S. bishops’ Ad Hoc Committee on Religious Liberty that was created to address the growing threats to freedom of religion, which the Constitution grants to everyone.

The election of President Donald Trump in November significantly changed the landscape of religious liberty, but it also raised a new set of questions. To discuss the implications of a Trump administration and religious liberty, as well as the current crisis in civil discourse in the public square, Archbishop Lori spoke with the Register Feb. 15.

Since the November election, the U.S. bishops have had the opportunity to discuss and assess the opportunities and challenges that come with any new administration. How would you characterize this early relationship with the new White House?

I would like to characterize it as one in which we are aiming for constructive engagement. There are areas of concern, and there are, of course, areas where we see some very important possibilities. Beginning with the latter, I would say that we certainly greatly appreciate the support on pro-life matters: The Mexico City Policy decision; the address of the vice president at the March for Life rally; the distinct possibility of a Supreme Court justice who may assist us in advancing the pro-life cause. These are all very, very good things and open up possibilities that we’ve really not had in the recent past. I would have to put that very much at the top of the list.

We remain hopeful that there would be a fairly broad executive order that would restore some of the religious-liberty rights that have eroded over the years through regulations and policies. We do not know whether or not that will happen, but we remain very hopeful, and we continue to advocate for it.

In terms of immigration, we do recognize the right of every country, including our own, to maintain and regulate our borders, and we also recognize the importance of following the rule of law. At the same time, not only the rhetoric, but also perhaps the language, with which the law is being enforced has raised up enormous concerns and fears among so many people, including our own Catholic people, including our growing Spanish-speaking communities throughout the United States.

I can tell you from my own experience here that our immigration services that we offer in the Archdiocese of Baltimore — and there are other kinds of services — are really being pressed, because so many people are so very concerned. So that would certainly be an area of concern for us, and the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops has spoken out about that.

In terms of refugees — and also we certainly have great concerns — we would hope there would be a recognition of the complexity of the situation in the Middle East, in particular, because we blithely speak of a Muslim ban, but in reality we have to look at the situation in a more holistic way.

Again, we have every right as a country to make sure that we control who comes in; and certainly every administration has the duty to make sure that citizens of the United States are kept safe, insofar as it’s possible to do this. We would certainly oppose any and all discrimination against Muslims as Muslims, but we would also recognize that there are a number of religious minorities in the Middle East who really need very careful consideration and protection: First and foremost are the Christians in the Middle East, who are not only persecuted, but who are facing extermination in many cases. I think about the Yazidis. I think about the Shias. It’s a very complex situation. And it requires, I think, a very deep understanding of that situation to craft a policy that is truly just.

And then, finally, I would mention retaining the executive order that would constrict the freedom of those entities that contract with the federal government, in terms of hiring. And so, for example, if you are a religiously based contractor that does business with the federal government, and your faith supports traditional marriage or supports the Church’s teachings on same-sex relations, this executive order that the Trump administration has held over from the Obama administration presents a problem. And that certainly presents a problem for things like Migration and Refugee Services, which is run, of course, by the bishops of the United States. So that kind of gives you, what I hope is, a waterfront look at some of the issues.

What is your assessment of the president’s proposal to eliminate the Johnson Amendment?

That’s, of course, a very complex question. We would certainly want to see, more specifically, what the president might have in mind. As a general rule, it is not a good idea for churches to engage in partisan politics. I believe that, generally, that proves to be a great distraction from our central task and mission, which is to preach the Gospel. Furthermore, I think it would have a tendency to unnecessarily divide our congregations.

I would recognize that the Johnson Amendment is lived out fairly unevenly, across religious lines, but in general, I think we would eye the adjustment of this amendment warily. I think that’s the best adverb I can give you. We are looking at this carefully and warily.

You have mentioned the Christian minorities and the religious minorities in the Middle East. You referenced the Yazidis and the Shiites. Religious liberties and freedoms are very much at the forefront in the concerns for Christians around the world. Do you expect progress on that front with the new administration, and what are your hopes with this new State Department?

We would certainly very much hope to make progress. I think there is, among the bishops of the United States, a growing sense of concern for religious minorities in the Middle East. There is support for efforts of working together in the Middle East.

We don’t recognize that, sometimes, Muslims and Christians are, in fact, working together in the Middle East. And, indeed, they are. In general, we would certainly want to work very closely with the new administration to protect the life and the well-being of religious minorities, including Christians, in the Middle East. This would include such things as making sure that where genocide is occurring we would continue to call it by its proper name; where we would speak out in the United Nations and in other forums, in defense of the religious rights and freedoms of these people; where we would seek to have the rule of law enforced in places like Baghdad or the regional government in Erbil.

I also think humanitarian aid is tremendously important, and funneling it and channeling it through organizations that are very much on the ground [is key].

I would like to mention the Knights of Columbus, which have done tremendous work in getting the situation of Christians in the Middle East declared already to be “genocide” and providing tremendous amounts of money to assist. I think about the work of Catholic Relief Services; I think about Aid to the Church in Need; Caritas: All of this needs to be supported.

These agencies are wonderful delivery vehicles for that kind of humanitarian aid. Finally, I think our immigration policy should be very much enlightened, in terms of the situation of people who are facing extermination or severe persecution because of their religious commitment, whether they are Christians or whether they are Shias or Yazidis.

We seem to be at a fairly low point in civil discourse. What advice can you give to Americans, and especially our elected officials and the media, on what civility in the public square should look like?

I would certainly agree with the comment that we have reached a low point in our discourse. To tell you the truth, I find it hard to watch the news and to see the shouting and the name-calling and the identity politics and the labeling that is going on. And it makes it impossible to search for some common ground, to return to values — that are very much at the heart of the founding of our country — and an ability to bridge our differences where we can and to act for the common good. All of that has been lost.

I think we all need to step back. I think we need to turn down the rhetoric, and I think that this is true of people on all sides of the political spectrum.

I think one of the roles of a religious community, one of the roles of the Church, is to lead the way by modeling that kind of civility, as we bridge our own difficulties and our own challenges, but also to form people to go out into public life and to be able to turn the volume down and to change the quality of the conversation.

I think there’s a big role in how we preach and how we help to form leadership as we move forward. I would also say while that is a long-term task, it’s also an urgent task, right now. We need to do this much sooner than later.

And what advice would you give those in the media, including Catholic media, on how to cover this sort of political divide?

First of all, I am always distressed when Catholic media imitates secular media and engages in this sort of labeling and name-calling, as if they were simply a branch of the secular media. We need to do better. We need to model how to do this better. It isn’t everybody, by any means, but there is enough of it that goes on that I think we should dispense with labeling and name-calling to the extent that we possibly can.

Secondly, I do think Catholic media has a unique opportunity to analyze things in such a way that the common ground, and basic values and truths, and the substance of the conversations can emerge. We have this tremendous tool in our Catholic social teaching that sheds light upon the issues we are facing in ways that transcends party lines, and we need to have enough unity ourselves in the Church that we can share the wisdom of this social teaching with the broader culture that will get a hearing.

I think that Catholic media, whether traditional or electronic, has an opportunity to contribute to discussion, and an obligation to do so, given the sorry state that [cultural dialogue is] currently in.

We just had what was a fairly monumental March for Life. Many people had anticipated a different outcome in this last election. Going forward, what would be your advice to the whole pro-life movement, given this new set of circumstances, and what is your suggestion of things to be careful about as we move forward?

That’s a very good question. First of all, I think my advice — I’m a pastor; I’m not a politician or a strategist — my first recommendation is that we double down on prayer.

I believe that prayer has always been the mainspring of the pro-life movement. Prayer is what enables us to advance this cause charitably, and lovingly and persistently and wisely, so I would say prayer would be No. 1.

Secondly, when the possibility of advancement comes, and even the possibility of a political victory, one danger is that you begin to overreach; a second danger is that you lose some civility; and thirdly is to equate a political victory with victory of the cause itself.

Even if we are able, let us say, to win protections for human life that we have been seeking for decades, we still have the task of winning over minds and hearts.

We have made some progress; we have made a lot of progress.

But that is the most important thing that we have to do, to win over minds and hearts.

The same is true of religious freedom: Even if the erosions we have experienced in recent years domestically could be reversed, we still have to do a lot of work to convince ordinary people of the importance of religious liberty and religious freedoms that need to be protected. So that would be my advice to the pro-life movement.

Never cease winning over minds and hearts, and you often do this by the love that we show to women facing difficult pregnancies; we do it by the love with which we speak about our cause; we do it by the sheer youthfulness of the movement, which was very much on display this year, as well.

So you seem to be giving advice, too, about the great importance of engaging in political life, while at the same time being on board as to who we are as Catholics.

Yes, certainly we are called to political engagement, and this is primarily the role of laypersons in the Church, not the clergy.

We are primarily those who should drive the vision, those who should provide formation; those who should provide sustenance and encouragement and spiritual strength. It is primarily for the laity to engage in the formation of a just and tranquil society.

How you go about engagement is important, because I think the political process is challenging, and I think it’s fairly easy to lose your soul in the middle of doing this.

So I think it’s important to figure out what the Church brings to this process.

Pope Benedict was very wise in his teaching on this — that the Church’s job is not to govern.

The Church’s job is primarily to teach. It is to advocate, it is to be a prophetic voice and to form people who will enter the political arena with wisdom and with charity. And those are the two qualities I think we need the most right now.

Of the virtues, charity would be the one you think especially Americans need to cultivate?

Yes, indeed. Politics is a good thing. It’s something that is a noble vocation.

But like every vocation, I think it has to be pursued virtuously.

For us as Catholic Christians, that means bringing to it a divine horizon: acknowledging God as the source of our rights and our dignity. God is the one who provides us with every good gift, and God pours forth his love upon us.

Then it means also, in the nitty-gritty of the decisions and processes of it, behaving as people who are truly virtuous, who practice the moral virtues in the midst of the give and take of political life.

Matthew Bunson is senior contributor

to the Register and EWTN News.

- Keywords:

- archbishop william lori

- march for life 2017

- matthew bunson

- persecuted christians

- religious freedom

- trump administration