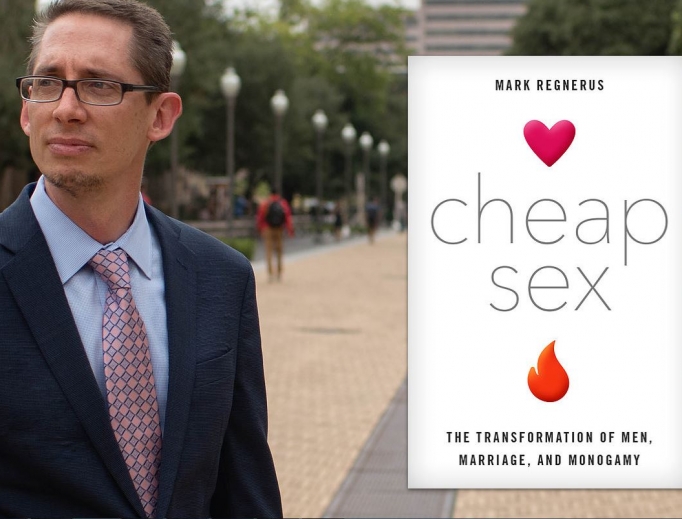

Sociologist Mark Regnerus Takes on the Economics of Cheap Sex

Cheap Sex: The Transformation of Men, Marriage, and Monogamy outlines the reality of 21st-century relationships.

Mark Regnerus was trained as a sociologist of religion beginning in 1995 and added the study of sexual relationship behavior about a decade later. Although his research reveals a world that is not what he as a Catholic would like it to be, he believes that, as Pope Leo XIII wrote in Rerum Novarum, “Nothing is more useful than to look upon the world as it really is.”

“I always want to know the truth about things,” Regnerus says, “and in these domains there is a great deal of misinformation, sculpted narratives and idealistic theorizing going on. I prefer realism, even if I’m not crazy about what I find.” In a written exchange with Register correspondent Judy Roberts, he talks about his new book, Cheap Sex: The Transformation of Men, Marriage, and Monogamy (Oxford University Press).

The words “cheap sex” have both a moral and an economic connotation. How are you using them in your book, and what do they describe?

I agree that it’s a loaded term, and at some level a disturbing one. Lots of people would prefer I not speak of sex in an economic fashion. It’s not supposed to work like that. I can agree that sex should not be “cheap,” but I would disagree with any suggestion that sex has nothing to do with exchange. Of course it does. You can’t wish that away.

The distinctions between men and women suggest that men are the ones who must give in order to receive. One of the central arguments of the book, and it isn’t that surprising, is that little is actually required of men today, on average. Sex is cheap — in a variety of ways and because of several developments I highlight.

In Cheap Sex, you present a “brave new world” of sexual relations that is also a very sad new world, particularly for women who are “learning to have sex like men” but also end up being subjugated to men’s interests. You say you are not writing an elegy for a lost era nor making a personal case for social change. What did you hope to accomplish with this book?

Like I mentioned earlier, this is about honesty and realism in a domain of research that is just swamped with idealism — both from the left and the right, from the secular and the devout. The pathways by which technologies cheapen sex needed to be mapped. And the book is also a generalist updating of what is known about the sexual behavior and relationship patterns of American adults. It serves multiple purposes.

You cite Anthony Giddens’ 1992 book, The Transformation of Intimacy, which talked about how the uptake of contraception “signaled a deep transition in personal life.” What evidence of this transition do you see in our contemporary mating and dating scene?

Where to start? Sexuality is something people now think of (or admit) as malleable, something to “cultivate.” We talk about a person’s sex life, rather than a relationship with another person. We decreasingly even remember that sex can generate life. Fertility seems like a design flaw now, rather than the primeval reason that sex feels good. We rank order sexual experiences. I could go on, and I do so in the book. Giddens was a prophet, really. His 25-year-old predictions have now materialized.

Other factors you mention as contributing to the development and proliferation of “cheap sex” are pornography and the internet. How do these relate to contraception, and how do all three work together to cheapen sex?

In brief, pornography is cheap sex — the cheapest, really. It undermines women’s ability to “charge more,” that is, to expect better treatment, more wooing and greater relational investment from men.

We tend to think of pornography as causing personal problems. But I focus on the social problem it poses for women in general, regardless of their own actions or that of the men in their life. By “internet” I mean online dating. The way it’s organized and distributed functions to treat human beings as rankable commodities and to speed up our ability to circulate through them. This is how online dating works. It can be navigated for good, but it really can’t be reformed in its baseline principles. It cannot reclaim the mating market that contraception has confounded and cheapened.

Cheap Sex makes the point that our culture’s rather dismal state of sexual relations is unlikely to change. Given the realities you describe, what are the implications for people who are trying to live counter culturally in this realm and prepare their children to do the same as they enter the world of relationships and dating?

My best advice is to not be blind. Willful ignorance might succeed, but more often it will only postpone problems. I also think that many of us do not actually value marrying cultures. If we did, we’d be taking steps to see it happen around us. Instead, we continue to raise the bar for marriage into the stratosphere. I know what will happen — the recession in marriage that is now occurring will only get worse. Stop talking about “deal breakers” and start thinking about “deal makers.” If you think a world in which few Christians marry will be a chaste one, you’re dreaming.

You talk in your book about how women are the sexual “gatekeepers” within their relationships. How is it, then, that we have the problem of a “rape culture” on college campuses?

Women are gatekeepers, yes, but they do not “set the price” by themselves. That is negotiated on terms that are decreasingly friendly to their interests. I say in the book that “hook-up culture” and “rape culture” are both children of the same parent — the split, gender-imbalanced mating market upon which I elaborate extensively.

College administrators remain unwilling to wrestle with the dark side of human personhood, concluding instead that enforcing speech laws will reform people’s motivations and actions. They want men to act better, but are unwilling to admit that men are more apt to do the right thing when they are socially constrained, not just individually challenged. And since women’s freedom to have sexual encounters will not be questioned, they are seeking instead to alter how their encounters must transpire. And you thought in loco parentis was dead!

On the one hand, it is heartwarming to see universities wonder aloud about how to ensure the sexual behavior of their students could be more wanted and mutual. On the other hand, presuming the sex act is malleable by fiat and subject to bureaucratic oversight is utter hubris. And how many new administrative positions will that require?

Who are the winners and losers in the new world of sexual relationships?

It’s a mixed bag, and some who think they are winners actually suffer in other ways. Careerist women get what they want — more time to study and commence work and postpone childbearing. They are no doubt successful, and the world benefits from their contributions. But many of them have exchanged something in return — control over how the romantic relationships in their life proceed.

The wealthy, of course, manage to figure out how to exploit new opportunities provided by the new regime. For example, real estate in urban cores is exploding in price as more couples work and delay childbearing — a result of the uptake of the pill. One income there will not suffice. And, yes, many lose something: Stay-at-home mothers struggle for the respect they perceive is given to career-focused women. Not a few men fail to see that high-quality spouses don’t stay on the market forever. Many men and women bring forward a self-centered mentality into marriage, which is not designed for it. I could go on. It was a trade-off.

You say in the book that relationships and their norms and rules favor men’s interests and that the route to marriage, which most women still want, is more fraught with more years and failed relationships than in the past. It sounds like women are giving more than they are getting when it comes to sexual relationships. What has gone wrong in the culture’s effort to liberate women not only from pregnancy as a consequence of sexual relations, but from the dominance of men?

It’s certainly true that women give more than they get today. But you have to stop talking about culture as if it is an actor somehow. It’s not. Nothing really went wrong in terms of what one should expect. What happened was predictable.

As I assert in the book, the only paradox here is the unrealistic expectation of so many that the securing of ample resources independently of men should have no consequences, or only positive effects, on the success of women’s intimate relationships. It’s not surprising that women would hope for it. The emotional energy bred by success would seem to be transferable. But sex and even marriage are, at bottom, exchanges. If women no longer need men’s resources — that which men can and will always be willing to exchange, if necessary — then relationships become far more difficult to navigate because strong commitments and emotional validation are just plain less necessary (and thus slower to emerge) from men.

Women still want them — they want love, which is a noble pursuit — but the old terms that prompted men’s provisions are on the rocks. There is no paradox here. Rather, it is what we should expect. That we are surprised at this development is telling of just how idealistic we are. We should be realists about how people actually are and how relationships work.

Do most people who engage in cheap sex sense that something is amiss or are they unable to see this because it is all they’ve known? Did those your team interviewed indicate they would be open to a different path or capable of following one?

Both. They feel like something is off, but they can’t name it. I include a variety of personal narratives where this tension is obvious. It’s hard to say whether they’re open to something different. When it’s all you’ve known, the models are pretty firmly established. I wish them well, but I’m never surprised when troubles befall them.

One of your eight predictions for the year 2030 is that organized Christianity will not stem the retreat from marriage in the United States. What does this say about a faith that is called to be salt and thus preserve what is good in the culture?

Christians are retreating from marriage, too, just at slower rates. We talk about changing culture. But it’s not so flexible. What does it say about the faith? It says that Christians want it all. But what they want is what they cannot have — both a culture in which marriage is normative and expected, together with all the desired fruit that won’t allow that to happen (greater freedom, choice, flexibility, time and opportunity).

We keep thinking that somehow we can change this. It cannot be changed under current conditions. Rather, think about how Christian communities, families, relationships and persons ought to live in light of it. They will need the help of each other — social and financial — to thumb their nose at the culture.

Register correspondent Judy Roberts writes from Graytown Ohio.

- Keywords:

- judy roberts

- mark regnerus

- marriage

- relationships

- sex

- sociology