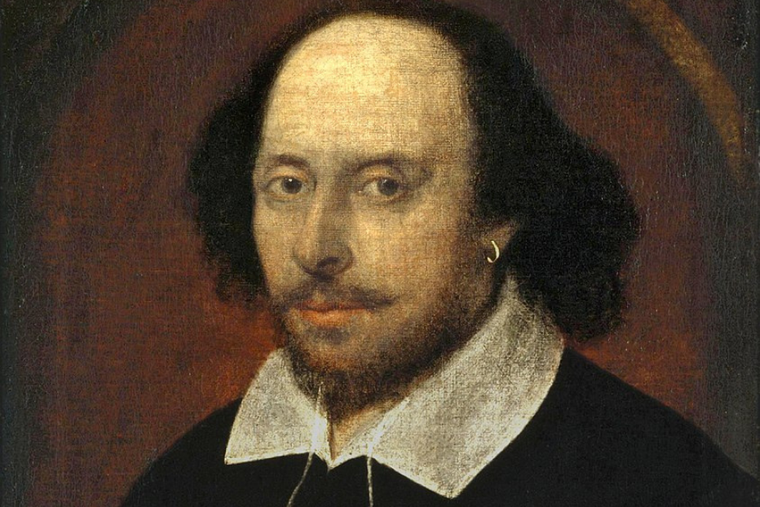

Shakespeare’s Relevance in Today’s World

COMMENTARY: A convincing case can be made to support the claim that the Bard is the most relevant writer who ever set pen paper.

In our topsy-turvy world, where Catholic churches are being vandalized while the omnipresent “Pride” flag flaps in the breeze, honored and unharmed, it is not surprising that strange things are brewing in the field of education.

And indeed they are.

The cry has gone out for new writers who are relevant to our time and to dispatch certain writers of the past. Be more “inclusive” is the current mantra. And so, William Shakespeare, not to be numbered among those to be included, should be excluded. It makes no sense, but reason has been dethroned.

A convincing case can be made to support the claim that the Bard is the most relevant writer who ever set pen to paper. This is because he is eternally relevant. Hamlet’s “To Be or Not to Be” soliloquy is the most dramatic presentation of arguments for and against suicide ever proposed. Othello invites a discussion on racism while The Merchant of Venice has an unforgettable portrayal of anti-Semitism. Macbeth shows in vivid colors the dark side of feminism while King Lear reveals how a man can go off the deep end. The Tempest promotes a dialogue on the importance of marital commitment while Romeo and Juliet display the potential for teenage sexual passion.

I reserve a more extended case for the relevance of Shakespeare in the modern world, however, to Julius Caesar. While this play does not mention abortion, the most contested moral, issue of our era, it does lay the groundwork for how to rationalize murder as something positive, defensible, acceptable and beneficial to all.

These parallels in treachery, we call them, proceed in a threefold manner. First, there is the dehumanization of the victim. Secondly, convincing others that killing the victim is to his or her benefit. Thirdly, convincing others that killing the victim is to everyone’s benefit.

Think of Caesar, says Brutus:

“as a serpent’s egg which hatch’d would, as his kind, grow mischievous, and kill him in the shell” (Act II, Scene 1).

To facilitate abortion, the unborn child has been likened to a parasite, a vampire, an unjust aggressor and even a mere clump of cells.

Dehumanization erases the notion of murder. “Kill it in the shell” applies equally to the unborn as it does to the assassination of Caesar. The unwanted unborn child must be prevented from being a burden to the state just as Caesar must be prevented from becoming a tyrant.

Abortion spares a child an unwanted and unhappy existence. In Act III, Scene 2, Cassius states that “he who cuts off twenty years of life cuts off so many years of fearing death.” Brutus responds affirmatively:

“Grant that, and then death is a benefit; so we are Caesar’s friends, that have abridged his time of fearing death.”

The murder of anyone would exempt him from all future anxiety and suffering. But suffering is an inseparable part of life. Cassius and Brutus appear naive. But they are easily deceived because they are already committed to murder. Similarly, pro-abortionists who have firmly made up their minds about abortion are easily duped by empty rhetoric. Nonetheless, neither Caesar, Brutus nor anyone else stands to benefit from premature execution.

Thirdly, after a sleepless night, Brutus, decides to take charge of a conspiracy against Caesar. The assassination must take on broad appropriation. In this way the notion of murder is replaced by one of public service.

The evil face of murder, however, may persist. A serious question remains:

“Where wilt thou find a cavern dark enough to mask this monstrous visage? ... Not Erebus itself we’re dim enough to hide thee from pretension.”

Brutus offers an answer that is perfectly designed to disarm: “Hide it in smiles and affability.”

The rhetoric used to rationalize the murder of Julius Caesar can serve as a blueprint for approving and promoting the slaughter of countless unborn children. It is sometimes difficult for a person to resist rhetoric and live by reason. The dehumanization of Caesar, making his execution appear to be a benefit to all while approving the mayhem with smiles and affability, is designed to be irresistible.

Dante, on the other hand, would not be duped by the rhetoric of Brutus and Cassius. He placed them alongside of Judas Iscariot in the jaws of three-headed Lucifer, eternally gnashed for the unpardonable sin of betraying a friend for an abstraction.

As a good playwright, Shakespeare allows certain characters to remain victims of their own wickedness, without deceiving his audience. We witness the evil involved without being infected by it. In real life, the evil that appears on the scene is highly infectious.

Thus, a good playwright, especially one who is relevant to his era, has a moral message to which the real players on the stage of life are often blind. Is Shakespeare still relevant? Is anyone else more relevant?

- Keywords:

- william shakespeare

- abortion

- classic literature