Dozens of Catholic Villagers Reportedly Killed in Central Nigeria Raid

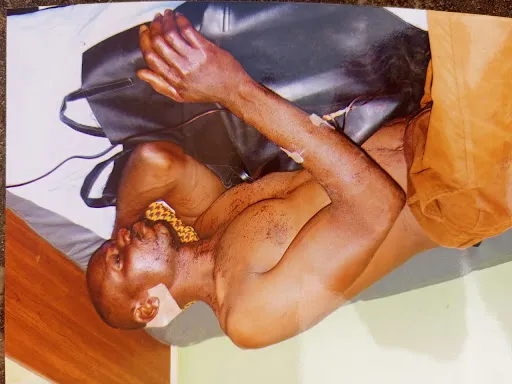

At least 71 residents of Gbjeji — virtually all of whom were worshippers at a parish branch of St. Michael’s Roman Catholic Church — were killed in the attack.

Details are still emerging after a violent raid by Fulani herdsmen Oct. 19 in Benue State, Central Nigeria, reportedly left dozens of Catholic villagers killed.

Police and clergy agree that the raid was in reprisal for the killing of four Fulani herdsmen earlier in the week in a clash between herdsmen and farmers defending their crops.

Accounts differ as to the exact number killed in the Oct. 19 raid.

A county chairman, Kartyo Tyoumbur, told CNA that at least 71 residents of Gbjeji — virtually all of whom were worshippers at a parish branch of St. Michael’s Roman Catholic Church — were killed in the attack. He said at least 35 bodies were found after the raid and 36 more bodies were recovered later in adjoining fields. The dead included women and children, along with two policemen, he said.

“The Fulani terrorists came at 6:00 a.m. and began shooting indiscriminately,” a local priest, Father Samuel Fila, who was outside the village at a clerical assembly at the time of the attack, told CNA in a text message. He said an estimated 200 attackers participated in a well-coordinated raid, burning houses and slashing fleeing villagers with machetes.

“The village is currently deserted,” he related.

However, Wale Abass, the Benue State police commissioner, provided a much lower death toll of “no more than 10, including one policeman.”

“The higher figures may be due to newspaper exaggeration or by the fact that some of the families take the corpses of their family members away from the killing zones before an official count may be made,” Abass told CNA in a telephone interview.

“We have a combined team of 20 police and 15 soldiers pursuing leads as to the whereabouts of the attackers and the local men who killed the herders,” he said, adding that no arrests have been made to date.

Benue State — which does not allow open grazing of traveling cattle herds — borders the states of Nasarawa to its north and Taraba to the east and has been the scene of frequent bloody terrorist attacks by Muslim extremists since 2019. The herding clans belong to the Fulani ethnicity, which claims up to 10% of the population of Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country.

Gbeji (pronounced (BEH-jee) is a remote farming town of 5,000 located two miles west of the state border with Taraba. Catholic villagers there receive ministry visits from St. Thomas parish in Afia, about 9 miles south of Gbeji.

The raid came in response to a violent clash earlier in the week. On Monday, Oct. 17, local farmers carrying single-shot craft guns had clashed with and killed four Fulani herdsmen whose herds were threatening the ripe crops, Father Fila told CNA.

“On Tuesday, herdsmen threatened an attack on the village,” he said.

The farmers throughout Benue State, often called the “breadbasket of Nigeria,” are facing crop reductions due to unusual flooding as well as the widespread fear of murder by armed terrorists when they attempt to harvest crops. Millions of Benue farmers and their families are living in displaced persons camps because they have been forced off their land by marauding militias.

A Fulani presidential candidate weighed in after the Gbeji massacre with his condolences to the grieving families in a Facebook post that some interpreted to contain a veiled threat.

“My deepest condolences to the families that may have lost a loved one and to the people and government of Benue State, “ wrote Atiku Abubakar, the presidential candidate of the People’s Democratic Party (PDP).

“The continuous escalation of intercommunal violence does not bode well for our national unity,” Abubakar wrote.

But the candidate implied that violence may continue so long as Fulani people are not welcomed into the Benue communities of farmers.

“When our people are well integrated into communities where they live, work, pay taxes and raise their children, they’d be obligated to reciprocate the love and acceptance.”

The statement drew barbs from political analyst Sesugh Akume in Abuja.

“Atiku calls a situation where people sleeping in their houses, on their own land and are attacked by marauders ‘clashes between farmers and herders,’” Akume wrote.

“He further calls it ‘intercommunal violence.’ If it is ‘intercommunal’ it means one community against the other. Pray tell which community had ‘intercommunal clashes’ with Gbeji? What is the name of the community?”

Akume alluded to the fact that large-scale attacks on settlements of Muslim Fulani people by Christian militia are unheard of in modern Nigeria, whereas hundreds of towns and villages in Nigeria’s Middle Belt states have been burned to the ground by Fulani terrorists during the last 10 years.

Benue Gov. Samuel Ortom has been petitioning the federal government for years to waive strict gun control laws that prevent him from equipping volunteer civilian guards with assault rifles to defend rural communities. Governors of other states in the Middle Belt have formed civilian guards for the same purpose in the face of rampant attacks by bandits and terrorists headed by Fulani people. At least 1,484 persons were killed in the Middle Belt states in the first half of 2022, according to data released by the Council on Foreign Relations.

- Keywords:

- 11 killed in nigeria

- nigerian christians