On Easter Night, the Upper Room Became a Classroom

After his Resurrection, Jesus had much to teach the Apostles, reminding them of mysteries whose true significance they were finally starting to grasp.

Last week, we focused on three elements from John’s Gospel: (1) Jesus’ gift of peace as his first post-Resurrection greeting to his Apostles; (2) his making them participants in that work of peace and reconciliation by commissioning them as ministers of peace and reconciliation in the sacrament of Penance; and (3) his revelation to “Doubting Thomas.”

Today’s Gospel, from Luke (24:35-48), brings us back to the same evening. As previously noted, the Apostles had probably been receiving all sorts of reports that first Easter. The account of the disciples on the road to Emmaus (24:13-33) is unique to Luke and, therefore, the return of those disciples to Jerusalem to inform the Apostolic college is the setting in which Jesus appears and our Gospel today begins.

Like in John, Jesus first also wishes them “Peace!” Luke, however, adds other human details, like … can this really be Jesus? Is it him? Or a ghost? So Jesus invites them in very tactile and sensory ways to convince themselves. “Touch me!” Poke and prod and be convinced of your senses — believe what you see, not what you think. And, lest they have any doubts while still needing to be brought down to this real, physical earth, Jesus asks a quite human and physical question: “Got anything to eat?” (v. 41). (What else might fishermen have but “a piece of boiled fish? V. 42).

Jesus’ encounter with the Apostles that Easter evening mirrors his encounter with the disciples en route to Emmaus: both groups need instruction. (To be quite honest, Jesus’ 40 days between Easter and Ascension seem taken up primarily with eating and teaching.) So, “He opened their minds so they could understand the Scriptures” (v. 45). Yes, the Messiah must suffer, die and rise. The consequence is that “repentance” and the work of reconciliation must be carried on.

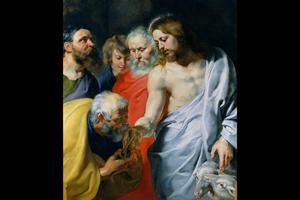

Duccio di Buoninsegna, the late 13th/early 14th Siennese painter, once more this year comes to our aid. “Christ Teaching His Apostles” or “Christ Taking Leave of His Apostles” captures this moment. The Upper Room becomes a classroom. Jesus is in the professor’s chair. His 11 Apostles (minus Judas) sit opposite him, like students.

Unlike some of the bored undergraduates in my life, these students are engaged. Eight are staring at Jesus, hanging on his every word. The three that aren’t fixed on Jesus have their heads lowered, as if they are pondering what they just heard or having that an “aha!” moment: “So that’s what Micah meant! I’ve been reading it all these years and never knew!”

These two postures — active engagement and meditative reflection — are appropriately depicted on the faces of the two Apostles closest to Jesus. One of those reflective Apostles – somewhat in the “middle row” with a black beard and reddish robes — does double duty: not only does he ponder but, looking in our direction, draws our vision into the action of the picture.

Was this painting intended to be associated with that Easter night encounter with Jesus? It’s hard to say for sure, in that Jesus’ clothing discreetly covers his appendages to conceal any wounds that might be there. The fact that we are down to 11 Apostles suggests its Paschal context. According to John, however, there should be 10, given Thomas’ absence, unless this event depicts the week after Easter. But the “Doubting Thomas” account is unique to John. It does not appear in Luke. We cannot assert anything on the basis of halos, because five Apostles lack them (simply because they would otherwise obscure their other, haloed colleagues’ faces). The “Taking Leave” title of the painting allows us to drop it anywhere in the 40 days.

Duccio is working in the very early Renaissance in “Italy,” so that we see a few medieval elements (flat faces, the gold of the halos blended with their faces) but Renaissance ones as well, e.g., the setting and architecture of the room and some of the attention to the Apostles’ clothes.

This is Jesus’ “graduate seminar.” Jesus clearly had a lot to teach the Apostles in a little time, reminding them of events and happenings whose true significance they might now be finally starting to grasp. That’s why Mark’s “Messianic Secret” now lapses. We know from elsewhere that, in speaking to the public, “he did not say anything to them without using a parable” while supplementing the Apostles’ instruction later (“But when he was alone with his own disciples, he explained everything” — Mark 4:34). We know also that “Jesus performed many other signs in the presence of his disciples which are not recorded in this book” (John 20:30). (St. Paul, for example, mentions Jesus’ post-Resurrection appearance to “more than 500 of the brothers at the same time, most of whom are still alive …” an event the Gospels do not expound — see 1 Corinthians 15:6.)

The Bible is not intended to “catch us up” with details mentioned here but not there, not even to provide us with a thorough biography. The Bible is intended, as a whole and in its totality, to foster and support our faith. And, as we were reminded last week in Jesus’ Beatitude to Christian believers in the face of Doubting Thomas — about being blessed to believe without having seen — what was recorded in Scripture is there so “that you may believe that Jesus is the Messiah, the Son of God, and that by believing you may have life in his Name” (John 20:31).

Nor is Jesus just teaching them. They must teach us. They must pass on the true faith in its integrity. Jesus is not “who we make him up to be” but whom the Church knew as an Incarnate Person, “true God and true man.” The Apostles do not go away with head knowledge but a mission, to “go and teach all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit” (Matthew 28:19; see also Mark 16:15-16, 20).

- Keywords:

- resurrection of jesus