Looking Ahead to the Resurrection

Here is the deepest truth of the human heart: that we are made for God, and that without him we shall surely perish, falling into a nothingness from which there is no escape.

Unless you’ve been snoozing your way through the season, we are very nearly done with the days and the disciplines of Lent. The good news is that Easter cannot be too far off. And have you noticed? Everything along the way is nudging us in the direction of that supreme moment when the Crucified God bursts through the gate and the grave of death to bring salvation to the world.

Two readings in particular seem to leap right off the page, riveting the attention entirely upon the coming conquest. Each of them pops right out at us from the latest Sunday Mass, that of the Fifth Week of Lent, in which we are given vivid and powerful reminders of the long-awaited Easter triumph.

Begin with Ezekiel, the fiery prophet of Israel, who gives us clear and stunning assurance that what God intends for humankind is nothing less than to throw open every tomb on the planet, his hands reaching down into the darkest places of all, there to summon forth all the dead to a renewed and resurrected life. When I heard that astonishing prediction at Mass, it seemed to me that I could not possibly have been alone in thinking at that moment of my own dead, imagining the look of complete rhapsodic surprise on their faces when Jesus comes to fetch them from the ground.

“Then you shall know that I am the Lord,” God tells us through the voice of his prophet. “I have promised, and I will do it, says the Lord.”

It is, without question, the best possible news God can give us. Leaving us all in the position of that enviable thief who, at Calvary, literally stole heaven in the last moments of his life. Can there be any other joy to compare with that, the sheer certainty of knowing death will not be the last word, that it cannot hold us forever? That Christ, the true Orpheus, does not return from hell with empty hands, but carries with him every Eurydice who, lost in the nether world far below, longs to return to the land of the living?

Not even the dissolution of the grave, in other words, will stand in the way of God choosing to snatch us from the jaws of death, so determined is he to rescue us from a final fall. Who among us would not, in the words of that lovely hymn written by St. John Henry Newman, wish to see “those angel faces smile / Which I have loved long since, and lost awhile?”

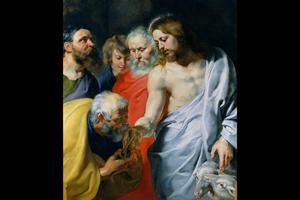

Of course, for that to happen, God must himself die. It is the price of our admission into paradise. Taking the form of the pierced and crucified Son, forced to climb the steep hill to Golgotha where, out of a depth of incomprehensible love for the Father and the world he came to redeem, he will slowly and protractedly be tortured to death. Only to rise in Easter triumph three days later!

And where else but in the story of Lazarus are we given a foreshadowing of all that? Next to the account of Christ’s own passion and death, it is the longest narrative on offer in the New Testament. Here is God’s showcase defense for the claim, long held by humankind, that hope not only springs eternal but that, thanks to the rising of the dead God, whom death cannot defeat, that same hope ensures final victory over the grave. Then will the chord of human longing be struck with the sheerest majestic finality by the One who, in the words of Hans Urs von Balthasar, “is so intensely alive that he can afford to be dead.” In whom all may thus share in the overthrow of death.

“One short sleep past,” as the poet John Donne reminds us, “we wake eternally; / And death shall be no more; death thou shalt die.”

The account in John’s Gospel is deeply stirring, revealing the truth that resurrection is real, that it holds out an ultimate transfiguration. Our hunger and thirst for God, for true atonement to take place, is not unfounded. And so Jesus says to Martha, sister to Lazarus, the dead man whom he has come to bring out from the silence of the tomb:

‘Your brother will rise again.’ Martha said to him, ‘I know that he will rise in the resurrection at the last day.’ Jesus said to her, ‘I am the resurrection and the life; he who believes in me, though he die, yet shall live, and whoever lives and believes in me shall never die. Do you believe this?’ (John 11:23-26)

She believes, knowing that never was an outcome more welcome than this, that despite the obvious expiration date stamped on the lives of those we love, our own included, it pleases Jesus to make exceptions for those who believe in him. “Yes, Lord,” she tells him, “I have come to believe that you are the Messiah, the Son of God, the one who is coming into the world.”

Here is the deepest truth of the human heart, the certainty of which the ever-practical Martha has seized upon: that we are made for God, and that without him we shall surely perish, falling into a nothingness from which there is no escape.

“What the soul hardly realizes,” Dom Hubert Van Zeller reminds us, “is that unbeliever or not, his loneliness is really a homesickness for God.” We belong to God, in other words, and nothing so defines us as the desire for union with him. “I am my beloved’s and my beloved is mine,” we are told in the Song of Songs, that masterpiece of the Holy Spirit, as St. Bernard of Clairvaux has told us. It is the claim which, in the light of Christ, we are all entitled to make, and Martha has come, on behalf of her brother, to collect his share.

“Here and there does not matter,” the poet Eliot tells us at the end of “East Coker,” second of the Four Quartets on which his lasting fame rests: “We must be still and still moving / Into another intensity / For a further union, a deeper communion …

In my end is my beginning.

- Keywords:

- resurrection of jesus

- lazarus

- lent