The Question No One’s Asking

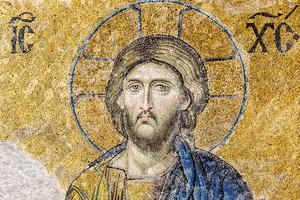

“Who do people say that I am?”

What could be worse than the answer to a question no one‘s asking? Here is Jesus, Son of the living God, putting before his disciples the single most sundering question: “Who do people say that I am?” Followed by that most amazing response from Peter: “You are the Christ, the Son of the living God.”

But suppose he had replied quite differently, in a way wholly unrecognizable from the New Testament record. Suppose he had said, “Well, Lord, I’m afraid there’s not much interest out there. You’ve stirred up so little excitement that the question hasn’t even come up. Maybe come back after you’ve made a bigger splash. Then we’ll talk.”

If evidence of such an exchange ever took place, Christianity would have imploded right there on the launching pad. Because if Christ isn’t God, and therefore the answer to the question that is my life, what possible point is there in signing on with the movement he founded? It’s a total washout.

Unless he was telling the truth, which means he is exactly who he reportedly said he was. “Before Abraham came to be, I AM.” In other words, he came from God, determined to rescue us from sin and death, from such bondage to Satan that his whole house of cards would need to come crashing down upon his diabolical head.

Could a mere preacher man have pulled that off? When Newsweek magazine revealed that only 52% of Americans actually believe that Christ was God, while insisting that he was a great moral teacher, it did not occur to the editors that even a mediocre moral teacher would never have said he was God. It would have been delusional to do so. Only a madman could imagine himself as God. Either that or someone deeply duplicitous. Such behaviors are hardly the practice of a good man.

If the evidence, therefore, prevents our choosing either alternative, which is that of Liar or Lunatic, then he really was who he said he was, i.e., the very Logos of God. What other option is there, then, but to follow him right to the very end? Indeed, in conforming our wills to God, we are launched upon a way that leads to an eternity that nothing else in this world can provide. If a man had made me a promise like that — a promise, moreover, vindicated by the evidence of an empty tomb — how could he not have produced an impression, leaving a huge reverberating splash in the great sea of history?

Why would anyone refuse an offer like that? Are their hearts so dead that even something as stupendously over-the-top as the promise made by Jesus not enough to stir the blood? Luigi Giussani tells us that there were two very different attitudes awakened by Christ. Either people had already figured him out, having smugly solved the whole problem of God, thus consigning both he and his words, “to fall like stones into the ocean of their indifference.” Or they would hang upon every word he spoke, their hunger for eternal life so great that nothing less could ever satisfy, ever assuage, the human heart.

There will never be a news bulletin as necessary to know, nor as consoling to receive, as the assurance given us by Christ: “Truly, truly, I say to you, if anyone keeps my word, he will never see death” (John 8:49-51).

Could it be that people who do not believe this, who persist in refusing Christ’s invitation, simply do not know their own heart, that they are unaware of its innate hunger for God? “What the soul hardly realizes,” writes Dom Hubert von Zeller, “is that, unbeliever or not, his loneliness is really a homesickness for God.” So profound is this need, this longing for our true home, that even the man who, as Chesterton says, knocks on the door of a brothel, is really looking for God. Yes, he’s come to the wrong door, but given a bit of grace he may yet find the right one.

Why this almost fatal lack of desire for God? Giussani, in an expressive phrase, has called this “the Chernobyl effect,” referencing the Russian nuclear disaster that sent radioactive fumes over Europe back in the late 1980s. “It’s as if today’s youth were all penetrated by…the radiation of Chernobyl. Structurally, the organism is as it was before, but dynamically it is no longer the same… People… are abstracted from the relationship with themselves, as if emptied of affection, like batteries that last for six minutes instead of six hours.”

An exhaustion of spirit having fallen upon us, we are no longer interested in God. Or freedom. As for immortality, why would that matter when there is no life after death? The meaning of life? There isn’t any. As the late Philip Roth once put it, “You tasted it. Isn’t that enough?” That life ends — that is the meaning of life. You’ve had your portion, now it’s time to go. Why should it matter that after you die, there will be no pie in the sky?

“Where there is no vision,” Proverbs tells us, “the people perish.” Lacking any real sense of purpose to which they might harness the energies of the heart, people might as well be dead. In the absence of something to live for, what follows is a loss of the self, leaving one prey to the manipulations of others, especially those who exercise power. “Those who stand for nothing,” warns Chesterton, “will fall for anything.”

It is not only the power of the state we need especially fear, even as its appetite for control succeeds in tyrannizing over those who have lost the sense of who they are. There is a far larger and more insidious power, whose success in laying hold of minds and bodies is everywhere. And that is consumerism. Consider the far-reaching seductions of advertising, an industry that reduces everyone to the status of a consumer, of someone whose every impulse is to buy. How easily we have grown complicit to that particular nexus, defining ourselves more and more as “I am what I shop.”

To vanquish enemies like that, we need to speak like Peter, in the ardor of whose love for Christ we need to say something along these lines: “Lord, we really don’t get it. But if we go away from you, we’re lost. Because you alone have the words of everlasting life. And if we don’t follow you, we’ll end up in some bloody ditch eating this nothing-burger. And after that despair and death. So, what have we got to lose?”

- Keywords:

- jesus christ