The Italian Jesuit Who Taught Computers to Talk to Us

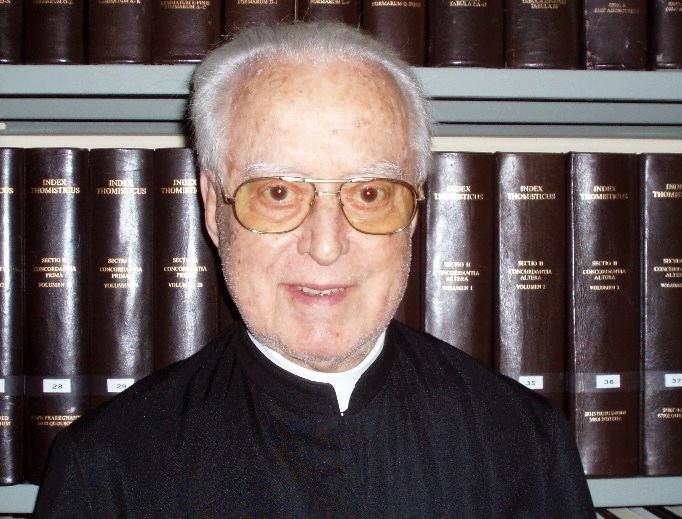

Fr. Roberto Busa will not soon be forgotten.

If you ever wanted to know who you should blame next time you lose that important PowerPoint presentation, it's a brainy Jesuit by the name of Fr. Roberto Busa.

Actually, it's not Fr. Busa's fault―you should backup all of your work nightly.

However, if you wanted to know who was the inspiration for allowing computers to understand anything more than strings of unintelligible numbers, it's, well… Fr. Roberto Busa.

As you sit there now reading this very cleverly written article, offer a prayer for the repose of Fr. Busa's soul. If it weren’t for him, you'd have to struggle to get anything done on a computer. Most likely, there wouldn’t be personal computers at all as they would only be available to people who understood their arcane vagaries.

And as long as we're regaling Fr. Busa, we should also thank him for creating hypertext―those delight links that lead you to yet other cleverly written articles, like these: http://www.ncregister.com/blog/astagnaro.

Yes, he did that.

Every time you use a word processor, use an Internet search engine, tweet, like, friend, post, pin, e-mail, scan, fax via computer or even Spotify, it's only because Fr. Busa was a visionary who refused to accept computer's simple nature as dumb machines but rather what they could become―capable of simulated reason.

Essentially, without him, there would be no such a thing as a computer keyboard.

Fr. Roberto Busa (1913-2011), an important pioneer in the usage of computers for linguistic and literary analysis, was a professor at the Pontifical Gregorian University and at the Catholic University at the Polytechnic in Milan from 1995 to 2000 where he gave courses on artificial intelligence and robotics. He also worked at the LTB project (Bicultural Thomistic Lexicon), which aims at understanding the Latin concepts used by Thomas Aquinas in the terms of contemporary culture.

Roberto Busa was born in Vicenza, Italy and attended school in Bolzano, Verona and Belluno. In 1928, he entered the Episcopal Seminary of Belluno where he earned his high school diploma. One of his theology teachers was Fr. Albino Luciani who was introduced to the world many years later as Pope John Paul I.

In 1933, Fr. Busa joined the Society of Jesus and earned a degree in Philosophy (1937) and Theology (1941) as is typical for Jesuits. He was ordained in 1940 and from then to 1945, served as an army chaplain in the National Army and later in the partisan forces.

In 1946, he graduated in Philosophy at the Papal Gregorian University of Rome with a degree thesis. His thesis was entitled "The Thomistic Terminology of Interiority," which was ultimately published in 1949.

He became a professor of Ontology, Theodicy and Scientific Methodology as well as a librarian in the Aloisianum Faculty of Philosophy of Gallarate, even though he never wanted to be a scholar. Instead, his principle desire was to assist the poor.

In 1946, Fr., Busa started work on his magnus opus―the Index Thomisticus―as a literary and research tool to search all of St. Thomas Aquinas' written works. This would be providential more for us than him but, sometimes that's how Providence works.

The Index Thomisticus is considered the beginning of the field of computational linguistics. The total work contained approximately 11 million words, each morphologically tagged and lemmatized by hand.

The project comprised of over 500,000 lines. He started his task by using 10,000 index cards.

In 1949, Fr. Busa met Thomas J. Watson, the founder of IBM, and convinced him to sponsor the Index Thomisticus Project.

The two met in IBM's New York City office. Fr. Busa asked Watson to team up on a project that would make word searches on a computer possible. Mr. Watson shook his head and said, "It's impossible for machines to do what you are suggesting. You are claiming to be more American than us."

The Jesuit did not give up and slid a punched card bearing the multinational company’s motto, promulgated by Watson himself, towards the CEO. It read: “The difficult, we do it immediately. The impossible takes a little longer.”

Fr. Busa turned to leave in a bid to challenge him. And, as one doesn't turn down Jesuits easily, Watson rose to the challenge saying: "All right, Father. We will try. But on one condition: you must promise that you will not change IBM’s acronym for International Business Machines, into International Busa Machines."

And, upon that fateful day, at that fateful moment, in a handshake between colleagues and geniuses, the computer became a great deal more "user friendly." The result of this meeting was "hypertext"—the overall structure of pieces of information displayed on a computer display, or other electronic devices, with references (hyperlinks) to other text which the reader can immediately access, linked to each other by dynamic connections that may be consulted on a computer at the click of a mouse.

That's the high falutin' way of saying computers were now capable of understanding the English alphabet and words in that language.

The term “hypertext” was actually coined later by Ted Nelson in 1965 referring to software that was able to memorize the history of a user's actions. However, as the author of Literary Machines admits, the idea predates the invention of modern computers. Technically, Fr. Busa really created hypertext at least 15 years before Nelson created his theoretical construct.

Fr. Busa spoke of that meeting with Watson in later interviews. "I had already informed him that, because my superiors had given me time, encouragement, their blessings and much holy water, but unfortunately no money, I could recompense IBM in any way except financially. That was providential!"

The joint Index Thomisticus Project ultimately lasted about 30 years. Finally, in the 1970s, the 56-volumes of the Index Thomisticus was printed. And, in 1989, a CD-ROM version of the Index was made available.

A web-based version of this massive work was made available in 2005, with special thanks to Fundación Tomás de Aquino and CAEL.

In 2006, the Index Thomisticus Treebank project (directed by Marco Passarotti) started the syntactic annotation of the entire project.

Fr. Busa's work lasted nearly 50 years, in which he devoted 180,000 hours.

Thus, Fr. Busa was able to catalog every word in St. Thomas' 118 books and an additional commentary from 61 other authors.

One would think that after essentially creating the Internet, Fr. Busa would simply have put his feet up and rested upon his laurels―to mix a metaphor. But this would be impossible for the truly gifted―more so a gifted Jesuit.

At the time of his death in 2011, he was hard at work creating software for automatic translation from one language to another.

Fr. Busa will not soon be forgotten. He even has a fan group on Facebook, “Padre Roberto Busa S.J.”

Fr. Busa even brought his computer knowledge — or should I say, "database" — into his theology describing God in terms a computer programmer could understand:

A mind that knows how to write programs is undoubtedly intelligent. But a mind that knows how to write programs which can write others testifies to a higher level of intelligence. The Cosmos is nothing but a giant computer. The programmer is also the author and the producer of it. We call God a mystery because in our everyday doings we cannot meet Him. But the Gospels tell us that two thousand years ago, He came down from Heaven. (Vatican Insider: “Father Busa, the Jesuit Priest Who Invented the Hypertext”)

Fr. Busa is understood to be the father of the new cross-disciplinary study called computational linguistics/digital humanities―the synthesis and cooperation of computational statisics with the world of language, linguistics, history, and other not strictly scientific disciplines and for his usage of computers for linguistic and literary analysis. In that, even Fr. Busa understood his place in history:

I feel like a tight-rope walker who has reached the other end. It seems to me like Providence. Since man is a child of God and the technology is a child of man, I think that God regards technology the way a grandfather regards his grandchild. And for me personally, it is satisfying to realize that I have taken seriously my service to linguistic research.