The 52 Martyrs of Kyoto

“It’s true! We die for Jesus! Blessed be Jesus!”

In October 1619, the Shogun Hidetada had just left Kyoto, the Emperor’s capital, when he was jolted by the news that the city’s jail held a great many Christians. Hidetada ordered that they all be burned alive, regardless of age, station or sex.

Kyoto had been visited by St. Francis Xavier back in January 1551. Hoping to meet and convert the Emperor, Padre Francisco had made a long, grueling winter’s trek much the length of Japan only to find that, without fine silk on his back and rich gifts in hand, he could not set foot inside the Imperial Palace. His empty hands and ragged clothes earned him only disdain from the palace guard.

His fellow Jesuits would soon return to plant Gospel seeds in that town, though — seeds that would find good soil in many a noble heart.

Thus, come Christmastide of 1618, the Feast of the Nativity was celebrated with all due devotion and solemnity by Kyoto’s Catholics — despite the fact that Hidetada’s father, Ieyasu, had banned the Faith in 1614 and Hidetada, now in command, was bent on expunging it with hellfire.

Outraged, some local pagans assailed the governor with complaints that the Christians neither feared the lord of all Japan nor respected his (murderous) laws.

At first, Kyoto’s governor, Itakura Katsushige, gave little credit to those complaints, for he knew his Christians to be model citizens. His son, however, fresh from the shogun’s court, warned of Hidetada’s wrath should he hear of Itakura’s leniency. Thus began a roundup of Christians in Daiusu-cho, a district known for its Catholic artisans and samurai.

Thirty-six of them were rousted out of their homes, strung together on one long rope, and dragged like dumb animals through the streets to Kyoto’s jail — a rank, pestilential hell like all Japanese prisons of the day, merely a holding pen for those condemned to die.

Meanwhile, on July 8, Hidetada arrived for a three-month stay at his villa on the outskirts of Kyoto, and the anti-Christian frenzy heightened. Edicts against harboring Christians were posted, and the jail soon held 52 Catholics.

Apparently, Hidetada, at leisure in his walled retreat, was unaware of all this until he started back for Edo (now Tokyo), but when he heard the jail was full of Catholics, the death sentence exploded out of him.

When that news reached the prison, all that could be heard within its dank walls was a resounding chorus of praise for Jesus Christ.

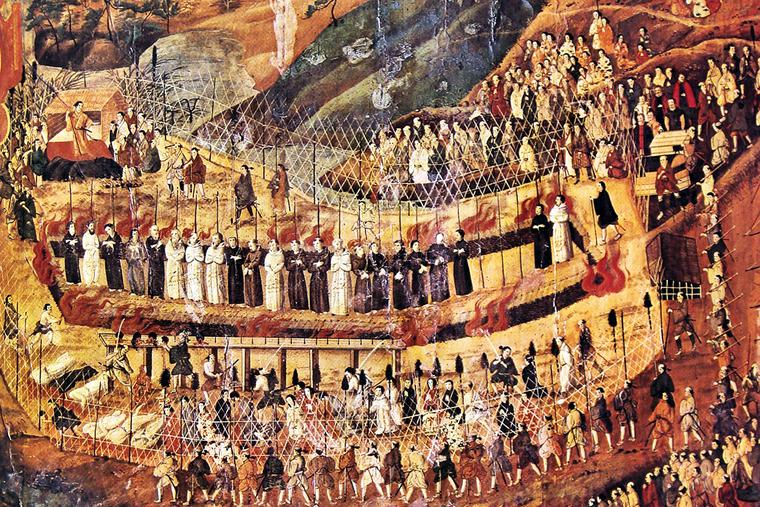

On the morning of Oct. 7, the 52 were led out into the sunshine and loaded onto nine wagons to be paraded through the city as a terror to would-be Christians before their immolation.

The men and youths went in the foremost and hindmost wagons, while in the middle rode the women and small children. A crier led the parade proclaiming Hidetada’s decree:

The shogun … wills that these people be burnt alive because they are Christians. And Hidetada’s will would indeed be done, but it would redound to the horror and admiration of all Kyoto and the glory of the Almighty.

For “a great multitude of people” lined the streets to watch the unfolding atrocity, and the martyrs echoed the shogun’s charge with, “It’s true! We die for Jesus! Blessed be Jesus!”

Perhaps it was Itakura’s high regard for the Christians that guided his discharge of the shogun’s orders. In executions by fire, the Japanese normally tied the condemned to simple stakes, but in this October holocaust, Itakura’s men had set up crosses, not stakes, on the dry riverbed at Rokujo-ga-hara — 27 crosses “so artfully finished and polished that it seemed they ought rather to be adored by the Christians than serve as instruments to put them to death.”

The prisoners were tied, not nailed, to the crosses two by two — men with men on the left, women with women on the right. And in the middle of the row of crosses, mothers were crucified with their small children.

Thus, Magdalena had her 2-year-old daughter, Reina, in her arms. Maria held Monica, age 4. Mencia held Lucia, age 3. Marta held Benito, age 2. Rufina held her precious 8-year-old Marta, who was blind. Tecla, who was about to give birth to her sixth child, was crucified with 4-year-old Lucia in her arms, Thomas, age 12, on her right, and Francisco, 9, on her left — five on one cross. Her other children, 13-year-old Catarina and Pedro, 6, hung on the next cross.

Contrary to the usual custom, “slow fire,” Itakura ordered an abundance of firewood to be piled up around the crosses so as not to draw out the martyrs’ agonies.

Evening came. The wood was lit. Flames erupted around the Christians on their crosses.

Mothers with little ones in their arms caressed their faces to soothe their pain. Cries of “Jesus!” resounded from the inferno. Gasps of horror from the crowd mixed with hoots from the executioners.

Catarina cried to her mother on the next cross, “Mama, I can’t see anything.”

“Call to Jesus and Mary, my beloved,” Tecla answered as she held Lucia on her swollen belly. “We’ll see them soon in Paradise.”

Richard Cocks, an English Protestant who witnessed this holocaust, wrote:

“I saw fifty-five martyred at Miyako [Kyoto], at one time when I was there, because they wold not forsake their Christian Faith, & amongst them were little Children of five or sixe yeeres old burned in their mothers armes, Crying out, Jesus recive their soules.”

For seven days, Itakura’s men guarded the martyrs’ charred remains lest local Christians steal away with them for proper burial and veneration. Historian François Solier reports that a large, resplendent comet appeared that first night and a great light shone in that same patch of sky the next night. Another historian records “supernatural fires” on high.

Perhaps Itakura’s men stood guard with eyes uplifted, wondering and perplexed at those signs in the heavens. Signs, no doubt, that Christ himself had been there among the martyrs, the Conqueror of Death claiming victory from those hellish flames.

Luke O’Hara became a Catholic in Japan. His articles and books about Japan’s martyrs can be found at his website, kirishtan.com.