On Divine Mercy and the Ironies of God

Sin matters to God and his holiness can never abide it. But sorrow matters more.

If you happen to be in the irony industry, intent therefore on cranking out endless examples of that particular product, here is one that only God could produce. It is the story of King

David — “a man after God’s own heart,” we are told — who founded the Judean dynasty and managed to unite all the tribes of Israel under a single monarch. Who, notwithstanding the highest possible praise heaped upon him by Almighty God, turns out to have been the same fellow who treacherously arranged the murder of the man whose wife he seduced.

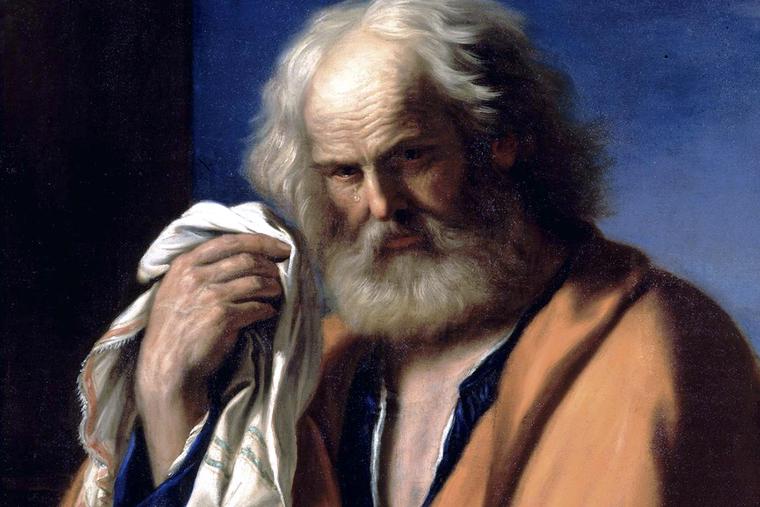

Now there’s an irony for you. If it be true that God writes straight with crooked lines, then here surely are some of the most crooked lines ever seen. And yet, however shocking and perfidious his behavior appears, doesn’t it more or less put him in the same basket of deplorables in which the rest of us may be found? Certainly, Christ’s closest apostles behaved no better. Almost without exception, they either betrayed or denied or simply ran away while he — the Absolutely Innocent One — was led away to die.

And let’s not forget the murderous Saul who, not long after his Damascus experience, confessed himself to have been “the least of the apostles,” indeed, someone who does not even deserve to bear the name. “Because,” as he tells us in First Corinthians, “I persecuted the Church of God.” How sweeping an indictment is that? It is sheer self-lacerating admission of guilt, an acknowledgment no less that so depraved a man that he was, God really had no business raising him up to become the great Apostle to the Gentiles.

And then there is the example of St. Augustine, the chronicle of whose sins gave Lord Byron a good reason to read him so that he might then discover a few that he hadn’t as yet committed.

Let’s face it, there are few writers of Christian persuasion who provide as copious a testimony to the vileness of his life before the grace and the mercy of God descended into his soul in order to pry him loose from deep and persisting habits of sin. Why else does he call the most famous autobiography in history the Confessions? It is not only the longest letter addressed to God, but clearly the most searingly honest and compelling conversation a man could possibly have with God. Who, in bending over his nothingness, which Augustine painfully and at great length laid bare before the Lord, nevertheless mercifully sets him free from all the shackles that had bound him to the darkness of sin.

And while we’re at it, let’s not forget the author of “The Hound of Heaven,” Francis Thompson, who goes on page after page detailing the record of his villainy, which despite its being the most thrilling documentation of human sin, nevertheless cannot outlast the overmastering mercy of a God who shows himself in far greater pursuit of his soul than poor Thompson ever was in pursuit of bodily pleasure.

The Hound of God will have his hare in the end, Thompson tells us. “Those strong Feet that followed, followed after.” But always, he assures us, “with unhurrying chase, / And unperturbed pace,/ Deliberate speed, majestic instancy, / They beat — and a Voice beat / More instant than the Feet — / All things betray thee, who betrayest Me.”

As Jesus himself was to say to Blaise Pascal on that memorable night in which he appeared to him: “I have loved thee more ardently than thou hast loved thy sins.”

So what are we to make of all this? That sin simply does not matter to God, which is why he seems so ready to forgive it? Not at all. Sin matters supremely to God, because it is an affront to his sovereign and eternal prerogative as Creator and Ruler of the universe that all creation be subject to his absolute and holy will — but most especially creatures made in his image, for whom he longs to confer the perfect likeness of his Son. Why else did the Son of God become man if not in order for us to become God? St. Augustine nailed it succinctly in his exhortation that we must “rejoice and give thanks, for we have been made not Christians, but we have been made Christ.” And thus through the journey into divine love, “we become incorporated into the Body of Christ; and there will be one Christ loving himself.”

But, of course, none of us obey, nor are we especially moved by a summons even this sublime; which is why we have all fallen short of the holiness of God. Not only in Adam’s fall have we sinned all, but in the most unimaginably awful exercise of sin we have all conspired to crucify Christ. We killed the very One who came among us, not only to deliver us from our sins, but in fact to deify us for an eternity of bliss in the company of God.

Ah, but in the most stunning irony of all, the Father permits all this to happen, suffering the Son to undergo a most hideous and unjust death, in order that he might then turn all the tables of sin and death, Satan and his countless comrades in iniquity, quite completely on their head.

So, yes, sin matters to God and his holiness can never abide it. But sorrow matters more. Thus are we moved with the psalmist to cry out, “A broken and contrite heart, O God, Thou wilt not despise.”

- Keywords:

- divine mercy

- repentence