England’s Greatest Catholic Poet Anyone?

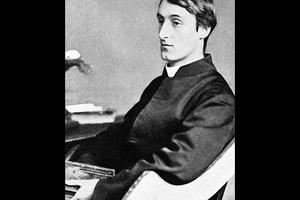

Who was Gerard Manley Hopkins and why should we read him?

After the death of Jesuit Father Gerard Manley Hopkins in June 1889, almost 30 years would ensue before the poetry for which he is justly celebrated saw the light of day. Another 30 years would elapse before their original integrity was restored, the first edition having been so thoroughly botched by people who hadn’t understood what he was doing. Even now, in fact, nearly a century and a half later, readers continue to be baffled and put off by the poems.

Many of my students, for instance, on whom I’ve been copiously inflicting his verse for as long as I can remember. They just don’t get it, even as they are often stunned by the rhythm and imagery of the work. The titles, too, have often proven to be wonderfully arresting. Who can resist a poem called “The Blessed Virgin Compared to the Air We Breathe?” Or, “That Nature Is a Heraclitean Fire and on the Comfort of the Resurrection?” If the aim of literature is to be, in the words of Kafka, “an axe for the frozen sea within us,” then the poetry of Hopkins is the perfect icebreaker.

Who was he and why should we read him? Especially Catholics, that is, for whom an understanding of Hopkins may provide a marvelous and incisive key to unlocking the central mysteries of our faith.

But first a word or two about his life, which, from the moment he chose to convert, was dogged by disappointment. By rejecting the empty ritualism of the Church of England for the deeper realism of Rome, a conversion catalyzed by the influence of St. John Henry Newman, who received him into the Church in 1866, Hopkins had pretty much burned all his bridges. His family reacted with sheer bewilderment to the news, which only worsened when he decided to become a Jesuit, no more odious an order than which can be imagined among 19th-century English Anglicans.

And then, of course, there is the poetry itself, which longed for an audience he never really had, owing not only to the oddities of diction and syntax, but to the fact that early on he’d resolved not to write any more. Renouncing the muse, he believed, seemed the least sacrifice he could make to God for granting him the gift of his vocation. And so, on entering the Jesuit novitiate in 1868, he made a holocaust of all his youthful verse. It was only after one of his superiors, seven years later, read about a shipwreck at sea in which hundreds drowned, including seven Franciscan nuns exiled from Bismarck’s Germany, and then wondered aloud if anyone might undertake to memorialize the event, that Hopkins offered to do so. Permission granted, he plunged at once into the making of “The Wreck of the Deutschland,” which has since become one of the enduring masterpieces of modern literature, despite the Society’s refusal to publish it.

More misunderstanding and neglect followed, including the appointment in 1884 to a professorship in Greek at University College, Dublin, where he labored amid an avalanche of numberless student exams which nearly drove him mad. Dublin was an awful place and within a few short years it left him dead from typhoid due to a polluted water supply, which the Jesuits were too cheap to try and remedy.

But the Dublin years, for all the wretchedness they brought down upon him, were not entirely wasted thanks to the poetry that resulted from them, most particularly those dark and terrible sonnets on which his reputation for lasting greatness rests. They are, simply put, an astonishment, evincing the great unassuageable hunger for God that stoked his soul from the start. Only now, of course, in these last weeks and months of a life that, more and more, he views as abject failure (“All my undertakings miscarry,” he writes. “I am like a straining eunuch. I wish then for death.”), God seems not to be there at all, his presence felt as sheer excruciating absence:

I wake and feel the fell of dark, not day.

What hours, O what black hours we have spent

This night! what sights you, heart, saw; ways you went!

And more must, in yet longer light’s delay.

With witness I speak this. But where I say

Hours I mean years, mean life. And my lament

Is cries countless, cries like dead letters sent

To dearest him that lives alas! away.

But the letters have not come back empty, have they? Nor have they been left unopened, their heavenly recipient indifferent to the laments of those who fear themselves lost. Any more than the tall gaunt nun, her cries piercing the darkness of the storm — “Christ, come quickly! Come quickly!” — has gone unanswered. Christ has come, will come; indeed, he comes for all of us. Because he has never left us, not once has he left us. Because he does not live alas! away.

And the most confirming sign that this may be true, that Father Hopkins too felt the reassuring hand, the imminence of a presence not of this world, yet there in that sickroom where he lay dying in order to beckon him to another world? It would be the very last words he ever spoke, words whispered while another Jesuit, a Father Wheeler, who was there to care for him, heard them on his rounds. Entering the room on the very last day of his life, he leans over the dying Hopkins to try and make out what he’s saying. “I am so happy,” he hears him saying. Again and again he will hear the same refrain: “I am so happy.”

- Keywords:

- Gerard Manley hopkins