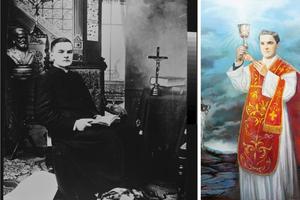

Father Michael McGivney Serves as a Model for All Catholic Priests

COMMENTARY: The manifest potential of the priesthood was fulfilled in Father McGivney’s holy life.

It is a Providential occurrence that Father Michael McGivney will be beatified Saturday in Hartford, during the year in which we mark the 150th anniversary of Pope Pius IX’s declaring St. Joseph’s the patron of the universal Church.

St. Joseph is a model for priests, particularly parish priests like Father McGivney (1852-1890). St. Joseph was a “just man” and every priest is similarly called to holiness. He had a fatherly love for Jesus and sacrificed to protect and provide for him; every priest is meant to treat Jesus in the Eucharist with the love with which Joseph held him in Bethlehem. He had a pure and reverent love for the Blessed Virgin Mary, a model for all priestly Marian devotion. He was a hard worker and model of diligence for every Christian, not to mention alter Christus. He was “most chaste,” as the Divine Praises reminds us, an example of the incandescently pure love that’s meant to burn in every priest’s heart. And he was a man of action. The Gospels don't record one word he says, but the Angel told him he was to name the Son of God “Jesus,” a fitting summary of his life, which bespoke that one word.

Father McGivney reminds me of all of these qualities of St. Joseph, but the one that strikes me the most is the last. We don’t have a single word Father McGivney preached. We only have a few letters or articles. Almost every priest or bishop raised to the altars — as well as most religious and laypeople — leaves a paper trail of prayers, theological insights, spiritual counsels and more. For Father McGivney, the only resource we have to get to know him, and imitate him, is, like St. Joseph, his deeds. And his deeds, like St. Joseph’s, point to Jesus.

There were some extraordinary deeds of charity. For example, after one of his parishioners, Edward Downes, died of “brain fever,” his wife Catherine discovered that there was no money at all to support her four sons. That meant, according to the practices of the time, that the Probate Court could assign the children to public institutions lest they be neglected for want of money.

Catherine Downes had to demonstrate that her fatherless children had someone to prevent them from becoming vagrants and support their education or apprenticeship. The oldest son was able to get a job and Catherine’s relatives were able to scrape together $2,500 for each of the two youngest sons. But no guardian was found to pay a $1,500 surety to become Alfred’s guardian.

During the probate court hearing to determine his fate, the judge asked if anyone would be willing to assume the responsibility. Father McGivney stepped forward. Even though he didn’t have the money for the bond, the judge accepted an arrangement with a local grocer who trusted the priest enough to insure the guardianship and thereby save Alfred from going to a public institution.

Another deed happened with 21-year-old James “Chip” Smith, a Catholic who was sentenced to death for shooting and killing a police officer. He was a bitter, very confused young man, and treated as a cop-killing pariah. Father McGivney visited him each day in the city jail, patiently talking to him, offering guidance and friendship and praying. Eventually Chip lost the chip on his shoulder and was reconciled.

On the day of his execution, Father McGivney offered Mass for him in the jail, accompanied him to the scaffold and blessed him. “Father,” Chip told him, “your saintly ministrations have enabled me to meet death without a tremor.”

There were many other routine priestly deeds: youth outings, baseball leagues for the men and boys, parish dinners and fairs, preparing parishioners for the sacraments, receiving converts into the Church, and trying to make St. Mary’s Church in New Haven and, later, St. Thomas in Thomaston, real centers of Catholic family life.

But the deed for which he is most known is founding the Knights of Columbus. The trauma of losing his own father and having to leave seminary, as well as seeing what happened to the Downes family and too many others, led him to want to found a fraternal benefit society that could provide security for families in the event of the death of their breadwinner. He also wanted to strengthen the faith of the men in his parish and to do something to counteract the anti-Catholic secret societies that were luring Catholic men precisely because they provided insurance in the event of sudden death.

After studying what other fraternal benefit societies did, Father McGivney and 24 lay parishioners founded the Knights of Columbus in the basement of St. Mary’s in 1882. He wanted it to be a self-governing organization, even though lay-led organizations in the Church were very rare, with his serving as a chaplain and adviser.

From that humble beginning, the Knights have grown over the past 138 years into the largest society of Catholic men in the world, with 1.9 million members in 17 countries. They continue to provide spiritual support and affordable life insurance policies to its members, but do much more. The Knights fundraise and donate $185 million annually to the Church’s worthy causes and dedicate 75 million volunteer hours.

I am very proud to be one of that band of brothers Father McGivney founded. I have been a member of four councils, including one I helped to found in a parish basement, and two for which I served as chaplain. I have published booklets on manly spirituality for them and contributed to their monthly magazine. And during my time serving the Holy See at the United Nations, I have been honored to collaborate with them in several events about the persecution of Christians as well as to promote St. Teresa of Calcutta and her message of peace.

Pope St. John Paul II wrote in 2001 that we should not think of holiness “as if it involved some kind of extraordinary existence, possible only for a few ‘uncommon heroes.’” Pope Francis in 2018 spoke positively of what he termed “middle class holiness” seen in the “saints next door.”

For me, Father McGivney is a model of the day-to-day, blue-collar holiness to which every parish priest is called. He wasn’t St. Augustine in the pulpit, St. Thomas in the classroom, St. Charles Borromeo in administration, or St. Pio in stigmatized prayer. He was Father Michael McGivney, but sought to respond to his priestly vocation and the work given him with the same wholehearted devotion as the others. That’s why he’s a great model for every priest and why his beatification Saturday is such an important event for parish priests and for parishes served by them.

In the best biography of Father McGivney, aptly entitled Parish Priest, authors Douglas Brinkley and Julie Fenster said that they wanted to write a book about him because he was “the most unassuming of Catholic clerics” and “just a parish priest.” The heart of Catholicism, they emphasized, “lies with the parish priests, who become so much a part of their parishioners’ regular lives. They celebrate Mass, baptize infants, visit the sick and dying and preside at weddings and funerals.” It’s to parish priests, they said, that Catholics turn in times of personal crisis.

By writing about Father McGivney, they emphasized with italics, they were “embracing that very obscurity and so honoring all parish priests,” whose stories, “if they are told at all, are buried in parish newsletters and local newspapers.” They hoped that their work would “help to instigate fresh thinking on the priesthood and its manifest potential.”

We see the manifest potential of the priesthood fulfilled in Father McGivney’s holy life.

We pray that, as a result of his beatification, we will see it brought to perfection in many unassuming priests of action like him.

And we ask God through his intercession that the Knights he founded will continue to form men to be committed “practical Catholics,” giving the witness of unity, charity and fraternity that the Church and the world need more than ever.