28th Sunday in Ordinary Time – Be Grateful to God

SCRIPTURES & ART: Today’s Gospel makes clear Christ’s intent to make his salvation available to all peoples, and the importance of gratitude to God for all things.

Today’s Gospel is a lesson in gratitude, especially in gratitude to God, which is its own separate category.

Ten lepers approach Jesus. “Approach” is used advisedly, since Old Testament Law restricted how close lepers could come to a settled community, e.g., see Leviticus, chapters 13 and 14. They beg him, out of “pity,” to help them.

Jesus tells them to observe the Jewish Law (Leviticus 14:1-32) and, while they are en route to the priests, they are cured by the power of Christ.

At this point, we are about where we are in most of Jesus’ healing miracles. As we have repeatedly noted, Jesus healed people not because he was concerned with improving the public health of Israel or because he wanted to better people’s temporal lives. Because sickness and, ultimately, death are consequences of man’s sinfulness, Jesus’ redemption of humanity involves the whole human person, body and soul. Jesus’ healing miracle, therefore, have Christological significance: they tell us who he is and what God’s plans for our salvation are.

In the Bible, leprosy is the quintessential sign of sin. We’re not saying that leprosy was sinful or that lepers were greater sinners than anybody else. But the pervasive, destructive, deforming advance of leprosy in the body, together with its isolation of the sick person from others, mirrored in the physical world the pervasive, destructive, deforming and isolating corruption of sin in the spiritual life. Jesus heals us of that.

Today’s Gospel, however, focuses on a further aspect: gratitude.

All 10 lepers were cured. One, “realizing he had been healed,” returned to say “thank you.” “He was a Samaritan.”

Back in July, we met a Samaritan who did good. Today we meet one who receives good and is grateful for it.

In the context of Jesus’ times, this episode is another testimony to Christ’s intent to make his salvation available to all peoples, not just Israel. Luke does not tell us what the other 9 lepers were, but we might presume they were Jews. As Jews, they should have known better. They should have recognized their dependence on God. After all, as Abraham remarked two Sundays ago, “they have Moses and the prophets.”

The Samaritan, whom we’ve noted the Jews considered in some sense worse than pagans, was the one who — in their estimation — should have been distant from God. If the other nine lepers were Jews, one can wonder whether this Samaritan leper was even further isolated within that community of the sick and dying.

Yet that Samaritan was the one who “returned, glorifying God in a loud voice.” And Jesus acknowledges his “faith.”

Once upon a time, gratitude was considered at least a sign of good upbringing. As a child, I remember my parents making sure I wrote a letter to my aunts whenever they’d send me a present for my birthday. That parental influence stuck, which means the sense of the obligation of gratitude ceased to be an internal imposition and became self-appropriated. That's what spiritual growth entails. (Alas, do people still write thank you notes?)

Gratitude presupposes another virtue we met in recent weeks: humility. To be thankful is to recognize that a gift is a gift, not an entitlement, not something “owed.” And, if it is a free gift, it means it need not necessarily be given, which means acknowledging not just the gift given but the love of the giver behind it.

That’s true of any gift, but it takes on a qualitatively different dimension with regard to God. We owe God everything, including the very fact of our existence at this very moment that you’re reading this sentence.

Perhaps, as Americans swimming around in Anglo-American culture, we’ve unconsciously imbibed some degree of deism: God made the world but is somewhere far off, uninvolved in the day-to-day running of that world.

That is not how Catholics (or any orthodox Christian) sees things.

God IS. That’ why he tells Moses, “I Am who Am” (Exodus 3:14). God is in the sense that he is being itself: “all was created through him, all was created for him. He is before all else that is; he holds all things together in himself” (Colossians 1:16-17). As St. John reminds us, “apart from him, nothing was made that was made” (John 1:3).

So, if God withdrew his love and presence (which are, after all, the same thing) for a microsecond, the universe would collapse faster than you could say “Big Bang.”

That’s a reason to be grateful.

But it’s not that God needs that gratitude, any more than he needs creation itself. As the pre-2011 translation of one of the Prefaces for Ordinary Time used to put it, “You have no need of our praise. Our desire to thank You is itself Your gift. Our prayer of thanksgiving adds nothing to your greatness, but makes us grow in Your grace.”

Thanksgiving makes us grow in God’s grace, because it beat back the unhumble, prideful attitude of “being like God” (Genesis 3:5) that was the very first sin. Gratitude helps us realize the gifts of piety and of fear of the Lord, which means recognizing (1) God is God and I’m not and (2) because of that, it is proper that I should have a childlike gratitude towards the God who so loves me.

But — as we noted when we talked about humility — that requires getting beyond myself.

Gratitude to God is not an option. It is sine qua non to being in right relationship to God, because knowing who God is and who I am vis-à-vis God can only lead to gratitude or prideful self-apotheosis. In other words, to heaven or hell.

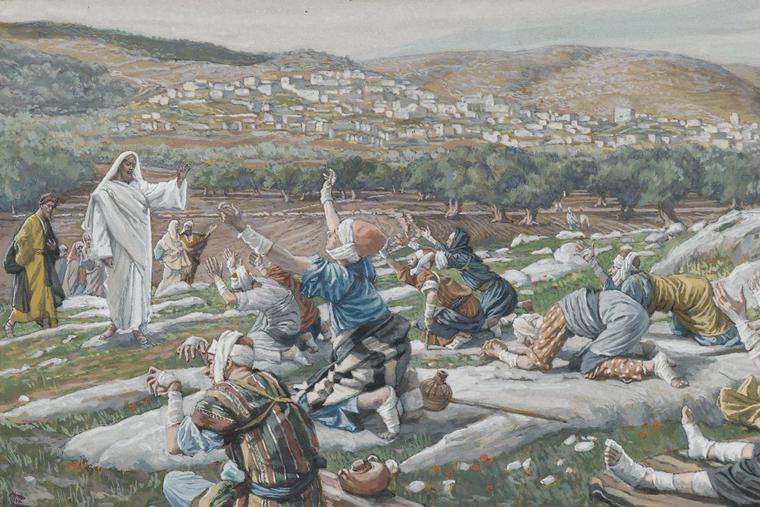

Today’s Gospel is illustrated by our 19th-century French friend and sacred artist, James Tissot (1836-1902). “Guérison de dix lépreux” (The Healing of the Ten Lepers) is a gouache (a modified kind of watercolor that makes it opaque) painting owned by the Brooklyn Art Museum. He painted it somewhere between 1886-94, about the time he was traveling to the Holy Land to make his “Life of Christ” paintings more authentic.

The scene is an encounter, Jesus and his Apostles on the left, the lepers on the right. Jesus is in his traditional pure white for Tissot. His approach put him in the forefront of the scene: it’s his face we see looking at the lepers, while theirs are rightly turned to him.

Jesus is right up front. His Apostles clearly are holding back, the one in brown on Jesus’ right not looking particularly happy about this meeting. The “field hospital’s” personnel clearly want to keep their distance, but the Divine Physician goes forward with his mission to heal. He is clearly instructing them what to do.

The lepers kneel, begging Jesus to “have pity.” Their bandaged limbs and heads are apparent. The leper closest to the viewer shows advanced stages of the disease: look at his deformed fingers.

There is a town in the distance, which reinforces the social isolation of lepers mandated by Leviticus because of the threat of contagion and spread.

One of these desperate men will be the grateful Samaritan. All of them will be better off an hour from now than they currently are. One of these desperate men will be the grateful Samaritan. Which one is it?

And would that one be me if I were in that picture?

- Keywords:

- gratitude