The Priestly Story Dioceses Tell: Reasons for Optimism in the US

Commentary for a Register Special Report on Vocations in the United States

While the Church in the United States faces serious demographic and geographic challenges that have continued to require parish closings in urban cores of cities in the Northeast and Upper Midwest, there is reason for optimism. According to the annual survey by the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate at Georgetown University, there were 590 men ordained to the priesthood in the United States in 2017 — an increase of 47% over the 401 men who were ordained in 2008.

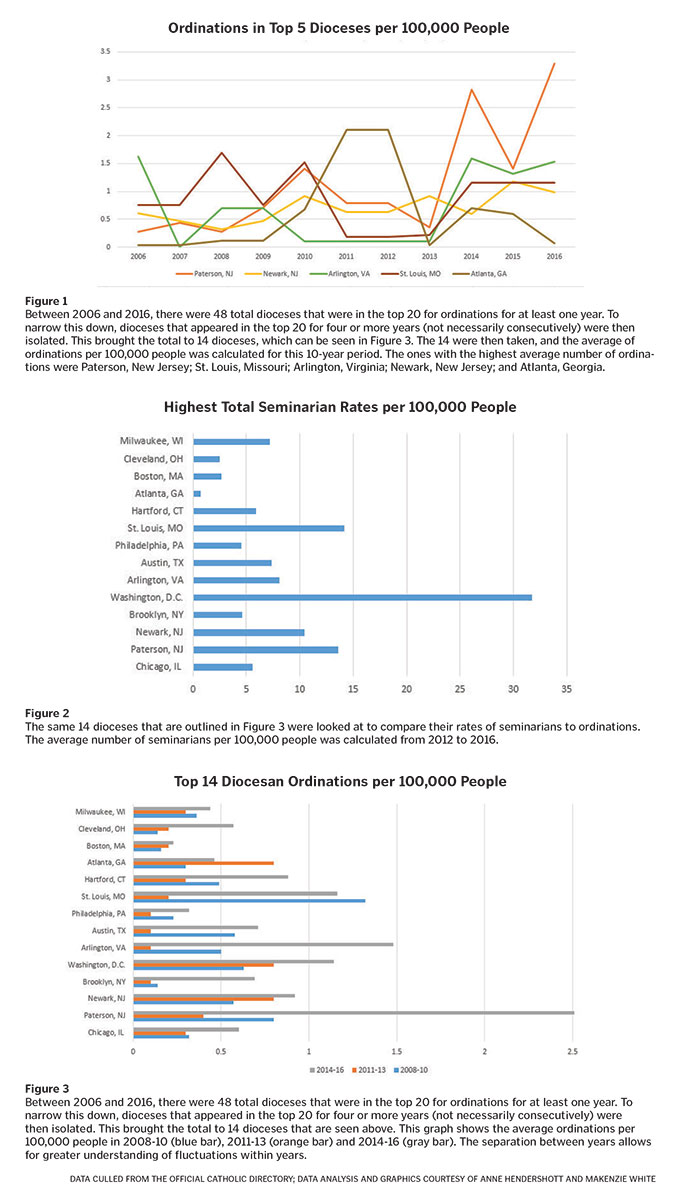

What is most striking about the data are the great disparities in priestly ordinations by diocese. While successful dioceses like Arlington, Virginia, and Newark and Paterson, New Jersey, have had dozens of ordinations over the past decade, other dioceses like Dodge City, Kansas, and Laredo and El Paso, Texas, have had several years of no ordinations at all — becoming almost like “mission territory” for Catholic priests.

A simple explanation for this disparity might suggest that the ordination-rich dioceses simply have a larger percentage of Catholics. For example, the ordination-rich Archdiocese of Newark has 1,318,557 (47%) Catholics out of a total population of 2,784,183. Likewise, nearby Paterson has 424,722 Catholics (38%) out of a total population of 1,129,405. But this simplest of explanations cannot explain why there are so few ordinations in several large dioceses with high percentages of Catholics — like Brownsville, Texas, where Catholics comprise 85% of the diocese with a population of 1,336,323 — and why small dioceses like Lincoln, Nebraska — where Catholics make up only 17% of the total population — had eight ordinations in 2016, surpassing some of the largest dioceses in the country.

We need to consider the cultural factors of a diocese — specifically, the role of the bishop, his vocations staff and the commitment by the laity to support vocations — as important variables in understanding disparities in ordination rates.

A now classic article entitled “Crisis in Vocations?” — published in 1996 by Archbishop Emeritus Elden Curtiss of the Diocese of Omaha, Nebraska — did just that.

Pointing to ordination-rich dioceses, including Peoria, Illinois, Arlington and Lincoln, where vocations were flourishing in the ’90s, Archbishop Curtiss wrote: “When dioceses and religious communities are unambiguous about the ordained priesthood and vowed religious life; when there is strong support for vocations and a minimum of dissent about the male celibate priesthood and religious life loyal to the magisterium … there are documented increases in the numbers of candidates who respond to the call.”

Sociologists Rodney Stark and Roger Finke provide quantitative data to substantiate Archbishop Curtiss’ assertions in an article in the Review of Religious Research published nearly two decades ago. Attempting to explain the declines in ordinations for some dioceses, data collected by Stark and Finke suggested that contributing to the decline in Catholic vocations were the radical revisions in religious roles interpreted from the Second Vatican Council. They argued that as the most central sacred aspects of religious roles, such as community life, distinct religious clothing and rhythms of prayer were dismissed or discontinued, “the sacred gratifications of religious vocations were thereby greatly reduced, as were features of the religious life that sustained and even generated these gratifications.” No longer were priests considered “a people set apart,” as the Council seemed to have “nullified the basic ideological foundation for eighteen centuries of Roman Catholic religious life” (Wittberg, 1994).

In their 1992 book The Churching of America, 1776-1990, Stark and Finke warned that “the more a religious organization compromises with society and the world, blurring its identity and modifying its teaching and ethics, the more it will decline.”

This is not to suggest that the Catholic Church must adopt a “conservative” solution to increasing priestly ordinations, but as Stark and Finke conclude: “A liberal church cannot motivate the intensity of commitment needed to fill positions requiring high levels of sacrifice.”

Their data, like our current data, point to the importance of orthodoxy and the crucial role of the bishop and his vocations staff in encouraging and nurturing vocations. We have found that the strongest predictor of an increase in ordinations in one diocese is the bishop’s success in increasing the number of ordinations in a previous diocese.

It is not a coincidence that Newark’s Archbishop Emeritus John Myers, who had presided over one of the most successful dioceses in the country in terms of numbers of ordinations, arrived in Newark after experiencing remarkable success in the Diocese of Peoria — one of the most ordination-rich dioceses in the country in the 1990s.

In fact, Archbishop Myers was so successful in producing priests in Peoria that he was featured in a 1991 feature article published in Newsweek entitled “Now Praying in Peoria.” The article’s author, Kenneth Woodward, lauded Archbishop Myers for having ordained more priests than Los Angeles, the nation’s largest archdiocese, and as many as New York — crediting the bishop for “re-priesting” Peoria’s parishes.

Beyond the raw data, which of course would unfairly compare large dioceses like Brooklyn to small ones like Burlington, Vermont, we see similar patterns. Controlling for the total number of Catholics in a given diocese by looking at the total number of ordinations per 100,000 Catholics, we find that the size of the diocese matters much less than the culture of the diocese. Laredo struggles to ordain any men to the priesthood — despite large Catholic majorities of more than 90%.

Some have suggested that ethnicity plays a role in explaining the lack of ordinations in some parts of the country, as Hispanic/Latino Catholics comprise about one-third of all U.S. adult Catholics but have ordination rates of only 15%. But ethnicity does not explain why some California dioceses with significant populations of Hispanic Catholics have much stronger numbers of ordinations each year.

Cultural factors — including the role of the bishop — play the far more important role. Just ask Catholics living in the Diocese of Madison, Wisconsin, where the number of seminarians has increased sixfold since the arrival in 2003 of an inspiring new bishop, Robert Morlino. And it is not a surprise to Catholics living in Arlington that Bishop Paul Loverde — who once led the U.S. bishops’ conference’s committee to encourage priestly vocations and who prioritized vocations when he arrived in Arlington in 1999 — welcomed some of the largest classes of seminarians in the country by the time of his retirement in 2016.

In an interview for Catholic World Report, Bishop James Conley of Lincoln said that the secret of a successful vocations program “begins with prayer.” In Lincoln, there are two communities of cloistered nuns who pray for vocations constantly. In addition to prayer, Bishop Conley suggested that one of the reasons that young men are attracted to the priesthood in Lincoln is due to “the security of knowing that the Diocese of Lincoln is 100% faithful to Church teaching on faith and morals.”

This is exactly what Archbishop Curtiss said back in 1996, and our data still demonstrate: Where there is orthodoxy, there are vocations.

Anne Hendershott is professor of sociology and director of the

Veritas Center for Ethics in Public Life at Franciscan University of Steubenville.

Makenzie White, who is a graduate student at the University of Pittsburgh, is Anne Hendershott’s research assistant.