Self-Sacrificing Love: Illinois Shrine Honors St. Maximilian Kolbe, Martyr of Auschwitz

A visit to the American shrine to St. Maximilian Kolbe in Libertyville, Illinois.

It was with great joy that my husband, Kent, and I discovered that the American shrine to St. Maximilian Kolbe in Libertyville, Illinois, was only an hour’s drive from our home.

His shrine is worth visiting for the sacred space for contemplation and for finding out more about this blessed man.

I “met” Father Kolbe for the first time in 2011 at Auschwitz, where he was murdered by the Nazis. I heard his story and visited the cell, now a shrine, where he died. A triangular monument, surrounded by four candles and a few bouquets of flowers, stood behind the iron grill on the prison cell.

I was intrigued by the fact that he gave up his life for another man with his heroic sacrifice at Auschwitz and that he was a man of the modern world, involved in newspaper publishing and thinking of making movies. He was a saint for modern times.

“Marytown,” as it is known, is a fitting tribute to St. Maximilian.

Marytown was founded by Franciscan Father Dominic Szymanski, a priest who knew St. Maximilian, according to Peter Ptak, Marytown’s media and data services manager. It was first located in Crystal Lake, Illinois, and then moved to Kenosha, Wisconsin.

When the friars needed more space for their apostolates, they moved to the current location in Libertyville in 1978.

The U.S. Catholic bishops declared the shrine to be the National Shrine of St. Maximilian Kolbe in the Jubilee Year 2000. It is a place of pilgrimage for the faithful and dedicated to promoting the witness and life of St. Maximilian Kolbe. It is a ministry of the Conventual Franciscan Friars of St. Bonaventure Province.

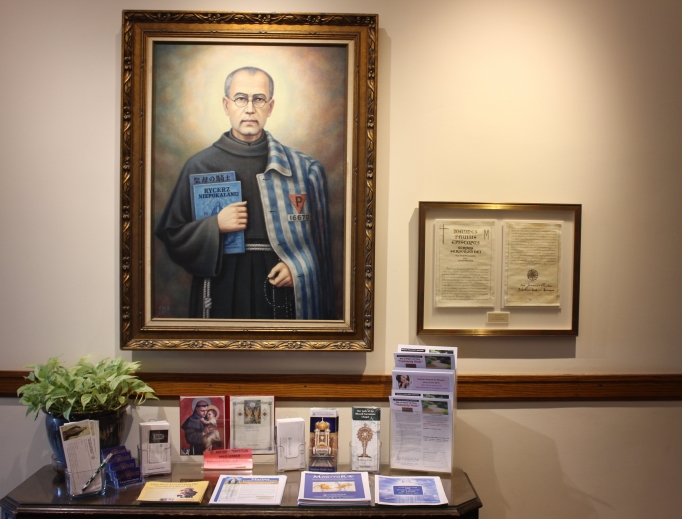

Today, on 15 acres, the National Shrine of St. Maximilian Kolbe includes a retreat house, conference center, gift shop and bookstore, a Holocaust exhibit, relics of St. Maximilian and several outdoor shrines.

The chapels are places of great beauty. The Blessed Sacrament has been adored perpetually on the grounds of the friars since June 7, 1928. The permanent chapel was dedicated Oct. 2, 1932.

At the center of Marytown is the Our Lady of the Blessed Sacrament Chapel, which is referred to as the “Third City of the Immaculate,” modeled after the evangelization centers created by Father Kolbe at Niepokalanów, Poland, and Nagasaki, Japan.

Noon Mass had just let out as we arrived. We were greeted by a group of Franciscan friars amid a background of organ music.

Some pilgrims had remained in the pews. Ahead of us was the shrine’s main altar, which is inlaid with mosaics representing the sacrifice of the Mass.

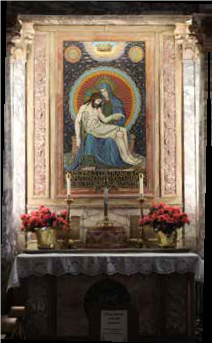

To the left, as one is facing the altar, is another mosaic depicting Maximilian rising above the flames of Auschwitz. Below the mosaic is a display of St. Maximilian’s relics. (There are also relics of Father Kolbe in the museum downstairs.) To the right, across the chapel, is the Sorrowful Mother Chapel. In the mosaic there, Mary is depicted holding the body of Jesus.

It is a tribute to the self-sacrificing love of a saint who once said, “Don’t ever forget to love.”

Wynne Crombie writes from

Huntley, Illinois.

INFORMATION

KolbeShrine.org

Selfless Witness

His name wasn’t always Maximilian. He was born the second son of a Polish weaver Jan. 8, 1894, at Zusak Wola, near Lodz, Poland, and was given the baptismal name of Raymond. In 1910, he became a Franciscan, taking the name Maximilian. He studied in Rome and was ordained in 1919. He returned to Poland and taught Church history in a seminary. He built a friary just west of Warsaw and founded the “Immaculata Movement” (Niepokalanów), which fostered devotion to Our Lady.

The friary eventually housed 762 Franciscans. They printed 11 periodicals, one with a circulation of more than a million. They were so successful that a radio station was installed. Father Kolbe even had plans for a movie studio.

In 1930, he went to Asia, where he founded friaries in Japan and in India. In 1936, he was recalled to supervise the original friary near Warsaw.

When Germany invaded Poland in 1939, Father Kolbe knew that the friary would be seized, and he sent most of the friars home. He was imprisoned briefly and then released and returned to the friary, where he and the other friars began to organize a shelter for 3,000 Polish refugees, among them 2,000 Jews. Then, in May 1941, the Nazis closed the friary, and Maximilian was once again taken to the Nazi death camp of Auschwitz.

At the end of July 1941, three prisoners disappeared from the camp, prompting the camp commander to pick 10 men to be starved to death in an underground bunker in order to deter further escape attempts. The 10 selected included Franciszek (Francis) Gajowniczek, who was imprisoned for helping the Polish Resistance. “My poor wife!” he sobbed. “My poor children! What will they do?” When he uttered this cry of dismay, Maximilian stepped silently forward, took off his cap and stood before the commandant and said, “I am a Catholic priest. Let me take his place. I am old. He, Gajowniczek, has a wife and children.”

Father Kolbe pointed with his hand to the condemned man and repeated, “I am a Catholic priest from Poland; I would like to take his place, because he has a wife and children.” His request was granted. Father Kolbe was just 47 years old when he died Aug. 14, 1941. The Church recalls this holy martyr each Aug. 14. During his imprisonment, Father Kolbe celebrated Mass each day and led the other prisoners in song and prayer. He encouraged them by telling them they would soon be with Mary in heaven.

Maximilian Kolbe was beatified by Pope Paul VI in 1971 and canonized as a martyr by Pope John Paul II in 1982. In attendance at St. Maximilian’s canonization was Gajowniczek, the man he saved. — Wynne Crombie

- Keywords:

- illinois

- st. maximilian kolbe

- travel

- wynne crombie