Professor John Rist: Why I Signed the Papal Heresy Open Letter

In an interview with the Register, the noted Catholic scholar explains what impelled him to sign the controversial letter and replies to some of the criticisms directed against it.

An open letter accusing Pope Francis of heresy and calling the world’s bishops to investigate has been signed by 86 people as of May 10, among them some prominent theologians and other academics.

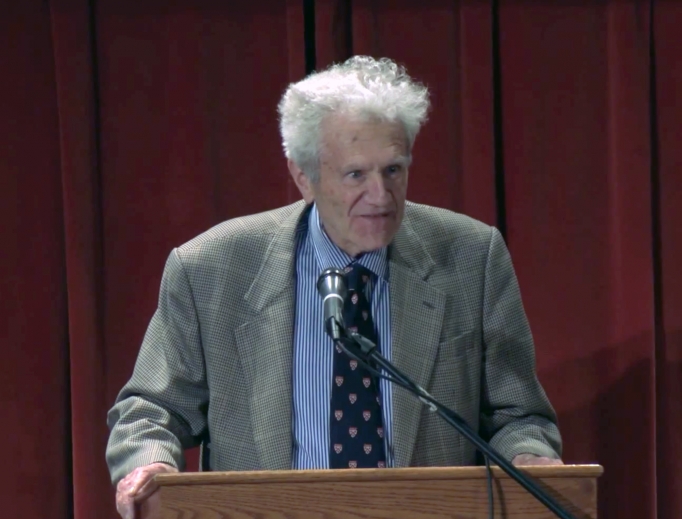

One of the most notable of the initial 19 to sign the missive is professor John Rist, a respected British scholar of patristics best known for his contributions to the history of metaphysics and ethics.

The author of detailed studies on such subjects as Plato, Aristotle and St. Augustine of Hippo, Rist held the Father Kurt Pritzl, O.P., Chair in Philosophy at The Catholic University of America and is a life member of Clare Hall at the University of Cambridge, England.

He was also one of the contributors to Remaining in the Truth of Christ, a book upholding the Church’s teaching on divorce and remarriage published ahead of the 2014 Synod on the Family. Cardinal Gerhard Müller, who was then serving as prefect of the Vatican’s Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, was another contributor to that 2014 collection of essays.

In this May 13 email interview with Register Rome correspondent Edward Pentin, professor Rist responds to a number of criticisms that the open letter has drawn, including that it is “extreme,” “intemperate” and “overstates” its case.

In response, he says he put his name to the initiative chiefly because he believes that what he sees as ambiguous statements from Pope Francis are designed to try to change the Church’s doctrine “by stealth.”

He says the letter is aimed at preventing “further massive confusion among Catholics” and to “expose papal double-talk,” which he believes is a deliberate effort by the Pope for “evading charges of heresy.”

Professor Rist, what were your own motives for signing the open letter?

My chief motive for signing was that I had come to the conclusion that so many vain attempts have been made to get the Pope to “clarify” his ambiguities and correct his seeming errors that there was no useful alternative to an outright “charge.” By his wholly unreasonable unwillingness, in particular to answer the dubia, Pope Francis has brought this upon himself.

How far has the letter achieved its goal?

I do not think the letter has achieved its goal — nor did I think there was much chance that it would, at least in the short run. That is because the Pope can always shelter behind silence, and there is a servile mentality among the episcopate (and many others, even conservative commentators), which is squeamish about criticizing a pope. Such commentators approximate too closely to reducing the sacred and unchallengeable dogmatic teachings of the Church to the utterances of a pope: the Father [Thomas] Rosica theory of the present papacy!

Why release the letter now, what prompted its publication, and how many people were asked to sign it?

I did not organize the letter so I cannot answer your questions. But I do know that there was considerable debate about the content. I was only involved relatively late on and agreed to sign because I thought the general approach was essential at this time. I doubt whether a document could be written in which everyone would agree with all the wording: that is, unless it were so bland as to be pointless.

What do you say to the various criticisms of the letter: that it represents an “extreme” and “intemperate” approach which “overstates” the case — as some see it — and this makes further criticism of this pontificate harder?

Criticisms of intemperance, etc., whatever their intent, can only have the effect of diverting attention from the main concerns: that the Pope is deliberately using ambiguity to change doctrine and that the attitude he adopts over appointments indicates that he is out of sympathy (to put it mildly) with traditional Catholic teachings on a whole range of subjects. Fussing about “extremism,” etc. seems like fiddling while Rome burns; what it shows is that even many conservatives do not want to grasp the gravity of a situation where the Pope seems bent on turning the Church into a vaguely spiritually flavored NGO.

Another criticism is that the signatories are not in a position to accuse the Pope of heresy, that only bishops can hold him to account for such a charge, and that the letter would have been better just calling on bishops to investigate the alleged heresies rather than accusing the Pope of them. What is your response to this view?

But calling on the bishops is precisely what the letter does! The signatories are not in a position to convict a pope of heresy; they are in a position to “prosecute” the charge, and we judged it was our duty to do so. The letter is primarily and immediately a challenge to the bishops to act rather than ignore or wring hands only.

What is your view of the critique that it’s not yet possible to accuse Pope Francis of specific formal heresy, but he can be accused of deliberate ambiguity and confusion, or “drift” toward heresy, and that that might have made a better critique?

See my answer above. I am not a canonist, nor (see above) a judge. What I am is someone who believes he can recognize intended heresy in word [and] also how the words are confirmed by the actions.

Others have said it would have been better to omit aspects which they believe are not strictly suspected of being heretical, such as supposed dubious episcopal appointments, protecting bishops who have covered up or committed abuse, and the Pope’s use of what some thought was a “stang” for a staff. What do you say to the criticism, that these are too extraneous to the accusation of heresy?

The list of “misdeeds” is cumulative. One or two could be ignored, but this number …? I fail to see how someone who, for example, calls abortion-activist (and abortionist) Emma Bonino a “forgotten great” can possibly believe the truth of Catholic teaching (going back to the Didache) on such an important matter, involving the deaths of millions by abortion.

What is your response to Jimmy Akin’s criticism that none of the signatories are specialists in ecclesiology and that the letter fails to show that Pope Francis obstinately doubts or denies dogmas?

Someone pointed out to me that Catherine of Siena has only an “honorary” doctorate “of the Church” and that, to the best of our knowledge, the apostles had no degrees at all!

Some of the criticism in this letter — including charges of syncretism, indifferentism and questionable appointments — has been raised to some extent about Pope St. John Paul II, as well. Are there any parallels here, and should his legacy be given greater scrutiny along these lines?

This is now a merely historical matter. John Paul’s theatrical talents, and his comparative indifference to Curial reform, have not been helpful. The former encouraged the disastrous practice, which we now see in spades, of assuming that if you want the answer to any question, you go to the pope as talking oracle: The media took (and takes) advantage of that, often to the detriment of the Church.

Are you concerned that in accusing the Pope of heresy, and especially if this accusation goes unheeded, you might be leading others to a sedevacantist position and disunity?

Some may, unfortunately, resort to sedevacantism. That would be sad but cannot be advanced as an excuse for inaction. Francis’ election does seem to have some uncanonical features (recognizable in the activities of the “St. Gallen mafia”), but elections in the past have also been dodgy. That is no justification for sedevacantism.

Which period of Church history do the troubles of our own time most remind you of?

At first sight there might seem particular similarities between the present situation and the rebellion of Luther. In both cases we had an overemphasis on a tendentious version of traditional teaching. Luther talked misleadingly about sola fides (saved by faith alone) — rather than the traditional fides caritate formata (faith expressed through love) — while the present German and Roman theologians seem to deal in sola misericordia (saved by mercy alone) without attention to Jesus’ call to reform one’s ways. But in our present case, a deliberate disregard of the recorded teachings of Jesus over “remarriage” while a spouse is still living implies either that Jesus did not really say what is reported of him or that his teachings have passed their sell-by date. This would accord with some Hegelian account of truth; however, that scenario implies a denial of his teaching authority and thus of his divinity. Which brings us to the most obvious parallel with the present situation: the Arian conflict of the fourth century.

Insofar as current German-Roman theology implies or suggests the diminished authority of Christ, it is Arian, not in the sense of a direct “subordinationism,” since now the subordination arises not from dogmatic theologizing but indirectly out of moral theology. Furthermore, while Luther was soon expelled from the Church, in our case, as with the Arians, it is an internal matter: bishop against bishop, bishop against pope (as Liberius was for a while in Arian times). As [Cardinal John Henry] Newman observed, the world woke up and found itself Arian. What are we going to find when we wake up?

Some noted that the letter was released not only on the traditional feast of St. Catherine of Siena, famous for her criticism of a pope, but also on the (postponed because of Easter) feast of St. George, the Pope’s name day. Do you see this letter not as a hostile attack on the Pope, as many have suggested, but as an act of fraternal charity? If so, do you think that could have been made clearer in the letter to avoid such criticism of hostility?

Some will see it as “fraternal charity”; others as an attack on the Pope. My own sole concern is to act, after the failure of others to elicit responses from the Pope, to help to prevent any further massive confusion among Catholics. The job of a pope is to encourage unity, not to become the leader of a faction.

What other concerns do you have that prompted you to sign the letter?

I am concerned above all else to expose double-talk, which is how the present Pope has been evading charges of heresy. Uttering ambiguous and/or contradictory remarks on important issues must ultimately be viewed as a planned attempt to change doctrine by stealth. Had such ambiguities/contradictions been occasional, they could be attributed — in accord with the canonical principle of benignity — to “mere” muddle. Prolonged ambiguity on this scale requires that a sadder conclusion be drawn: that there is a design to achieve by stealth what could not be achieved by openly and unambiguously un-Catholic decrees.

I end with a quotation from the greatest of Catholic doctors:

“We tend culpably to evade our responsibility when we ought to instruct and admonish [evildoers], sometimes even with sharp reproof and censure, either because the task is irksome or because we are afraid of giving offense, or it may be that we shrink from incurring their enmity, for fear that they may hinder and harm us in worldly matters, in respect either of what we eagerly seek to attain, or of what we weakly dread to lose” — Augustine: City of God, 1.9.

- Keywords:

- edward pentin

- heresy

- john rist

- pope francis