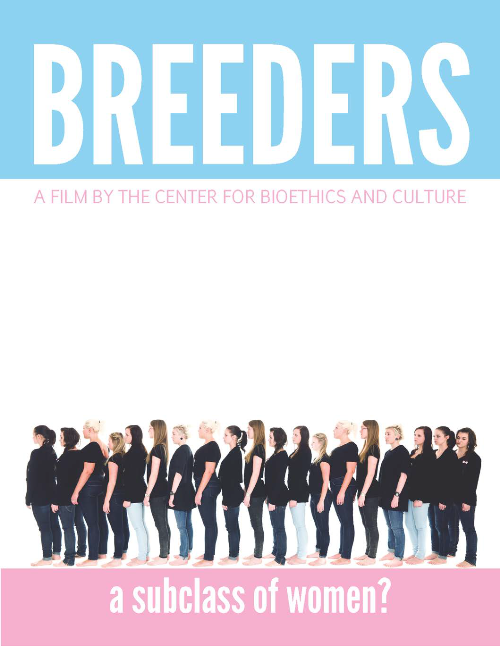

Jennifer Lahl’s ‘Breeders’ Completes Trilogy on Reproductive Technology

The new documentary film delves into problems arising from the surrogacy motherhood business.

Jennifer Lahl has just released her latest film, Breeders: A Subclass of Women?, which examines the unexpected problems that arise when women are contracted to serve as surrogate mothers and children discover that their conception was the outcome of a commercial transaction.

Lahl is the founder and president of The Center for Bioethics and Culture Network, which “addresses bioethical issues that most profoundly affect our humanity, especially issues that arise in the lives of the most vulnerable among us.” The center uses a variety of media platforms, including film, to bring “diverse voices together, across the spectrum of human experiences, building common cause in order to answer important questions.”

The Center for Bioethics and Culture Network previously produced the films Eggsploitation (2010), about the commercialization and exploitation of women for their eggs, and Anonymous Father’s Day (2011), about the multimillion-dollar sperm-donor market. The center also made Lines That Divide (2009), about the cloning and embryonic stem-cell research market. Breeders (2014) is being screened in cities nationwide, starting Jan. 27.

Lahl has a background in medicine and has worked as a pediatric critical-care nurse and a hospital administrator. She has emerged as an influential advocate for vulnerable women who have been harmed by the unintended consequences of reproductive technology. She was invited to speak to members of the European Parliament in Brussels to address the problem of egg trafficking.

On Jan. 15, Lahl answered questions posed by Register senior editor Joan Frawley Desmond about Breeders.

The women I meet in my work are what most inspire me to make my documentaries. I have been writing and speaking for over a decade on reproductive medicine and the ethics of these new, modern technologies. Through my work, I am contacted on a fairly regular basis by women who have been harmed by either selling their eggs or renting out their wombs. I also hear from people who were born because of these technologies and aren’t necessarily fine with their conception story. They want to change the practice of anonymous sperm and egg selling.

How does this film build on the themes explored in Eggsploitation and Anonymous Father’s Day? What is your ultimate goal?

The goal of our three-part documentary series on reproductive technologies is to tell the whole and full story. If you visit any fertility website, all you will see are smiling, happy couples holding cute, healthy babies. You won’t hear about the young woman who decided to sell her eggs to pay her college tuition and nearly died. And you definitely won’t hear from the children born this way who wonder who their biological mother or father is. Eggsploitation, Anonymous Father’s Day and, now, Breeders: A Subclass of Women? is our effort to educate the public about the real impact these technologies have on women, children and families.

A New York Times wedding notice for a same-sex couple mentions that they had a child through “a surrogate,” who goes unnamed. An actress announces that she had a child with the help of “gestational carrier.” Are feminists irate about the demeaning terms used to describe women who serve as surrogate mothers?

Feminists are no different than the everyday public. Some feminists, like the public, don’t have these issues on their radar, as they may be involved in issues of domestic violence, women and poverty, abortion rights or other feminist causes.

Some feminists, again, like the public, believe in absolute autonomy and the rights of women to do whatever they want with their bodies. Their body, their choice; like the libertarian viewpoint. Others, of course, are outraged by the objectification and commodification of women and children and the class issues. Wealthy women are not selling their eggs or renting out their wombs. It is largely women who have financial need.

The media often adopts a skeptical, even an adversarial, approach toward American business, yet the fast-growing assisted-reproduction industry is usually treated very sympathetically. What is going on?

Infertility touches us all. Most of us know someone who has used these technologies to have a baby. Many have much-loved grandchildren, thanks to a young woman or young man who has contributed their eggs, womb or sperm. It’s easy to go after big business or big pharma as corrupt, greedy and all about the bottom-line profit. It’s another thing to challenge anyone trying to have a baby.

Why is the United States the “wild West” of surrogacy and other forms of assisted reproductive technology?

America prides itself as a country of freedom and innovation, open to and leading the world in new technologies. Regulation typically comes after a new market is developed.

Cigarette smoking was regulated after we learned about the risks of smoking. Public smoking became regulated after we learned the harms of secondhand smoke. The pattern was the same with car safety, seatbelts and airbags. Bans on cellphones while driving came later, after risks were better understood.

Reproductive technologies really are still fairly new. As more evidence emerges on the risks and the harms, will the public see the need to ask our legislators to act? Many developed countries outside the U.S. have led the way in regulating these technologies; it is finally time for the U.S. to do so, too.

Was it hard to find women who were willing to tell their stories for a filmmaker?

I’ve been fortunate that most of the women I’ve interviewed in my films find me. The Internet, and social media like Facebook, is a great way to connect and find people around the world. I’ve watched the donor-conceived worldwide community join forces together on blogs, websites and social-media platforms and bring their voice to the public.

You traveled to India to report on the emerging surrogacy industry in the developing world, but it wasn’t easy to interview women there. Can you tell us what happened?

We hired a crew in India to do interviews with women who serve as surrogate mothers for our film because we wanted to show what is happening to poor women in third-world countries who are really treated like a breeding class. Our crew set up interviews, and when the cameras were rolling, the agency was not happy with the questions we asked, sensing that they were probing more of the ethics of surrogacy. Basically, they were worried our film was going to shed a negative light on the practice. The interview was abruptly halted, our equipment was damaged and the film confiscated.

We tried another day of interviews, and it was very evident that the women were being coached to only say positive things and were not able to speak freely, as the agency representative sat nearby watching. We are up against a strong, powerful and wealthy industry that doesn’t want to discuss the full story.

Your film features a young woman who was carried by a surrogate mother. How do the children feel after they learn the truth of their origins, and does it matter if their parents are heterosexual or same-sex couples?

Children born through these third-party arrangements often aren’t even told their conception story. Those born in same-sex couples can’t be lied to. The minute a child is old enough to understand how babies are made, he will be able to figure out that something isn’t right if they have two moms or two dads.

Children born into heterosexual families are easier to deceive. If a child is told, much of their reaction will be influenced by how and when they are told.

This is new territory, with very little data out there. We are in a brave new world, as far as these new, modern family situations.

In some parts of the West, same-sex couples have obtained the “right” to adopt or have children through assisted reproduction. How will that affect acceptance or incentives for surrogacy?

First, I don’t believe anyone has a “right” to a child. In fact, one of the experts we interviewed in Breeders said, “No one owes anyone a child." I agree. No one has a right to a child via adoption or surrogacy, and that is true whether you are in a same-sex relationship or a heterosexual relationship.

What is your next project, and do you see any signs of hope that Americans are learning that assisted reproduction, no matter how well-intentioned, can harm women and the children who learn that they were bought and sold?

I laugh when people ask me what my next project will be. I liken it to asking a woman in labor when she’s planning to have her next child. We have just released Breeders, and a few months ago we re-released and updated an expanded version of Eggsploitation. That’s two films in less than one year!

But we do have plans for more films and always have several ideas on our creative storyboard.

I am hopeful, when Americans are better and more fully informed, they will say, “We need to stop, or at least pause and think about what we are doing.” I’m encouraged when I do public screenings of the films and see how fast people come around and get that this is much more complex than they realized.

Many people assume that if someone wants a baby, they go to the fertility doctor, and nine months later they have a baby. It only works this way on websites and in Hollywood movies.