You’ve Seen the Photos—Now Here’s the Story Behind Them

But You Might Be Surprised to Hear Where Many of These Famous Pictures Came From

On Jan. 28, 2017, aged 94 years old, Lennart Nilsson, the celebrated Swedish photographer, died peacefully.

Just over 50 years earlier his book, A Child is Born, had caused a publishing sensation.

Stunningly displayed in its pages, and in an ethereal color, were images of embryos apparently still in the womb. For the first time, the camera had captured something of their mysterious translucent presence.

In the half-century that followed, a global audience came to admire what many considered to be some of the most astonishing photographs of the late 20th century. What was not known, however, was that many of the images in the book, especially of the older embryos, were of the aborted.

It took over a decade to produce the book that would come to be known as A Child is Born. A pioneer of the electron microscope, from the start Nilsson was in the vanguard of photographing the unborn. In the 12 years he worked on this book project, he was assisted by five hospitals that had agreed to collaborate with him. Some of the photographs were of fetuses from the earliest stages of pregnancy; often the subjects were obtained through miscarriage or ectopic pregnancies. During this journalistic assignment, however, Nilsson also turned to medical facilities carrying out abortions to help him find pictorial material. Abortion had been legal in Sweden since 1938. After the Second World War, the law was liberalized further; by 1965, in that country there were over 6,000 abortions per year. After having discovered suitable specimens, it is claimed, Nilsson would clean, frame and then light the aborted, before, finally, beginning to photograph.

It was a very different photographic assignment, this time at the United Nations, which took Nilsson to New York in 1953. While there, he pitched the idea of a photographic record of the embryo growing in the womb to Life magazine. At first, the Life editors were skeptical of the technical feat needed to carry it off. But then, the Swede showed them photographs of his earlier attempts; they were intrigued enough to commission the project. Those images were not of a live embryo though. Instead they had come about the previous year when Nilsson was completing another assignment at a Stockholm hospital. While there, the photographer saw in a glass jar filled with formaldehyde, and measuring mere centimeters, a fetus. Nilsson gained permission to take it home where for more than a week he photographed it.

In due course, the images Nilsson managed to record would later comprise a 16-page spread in April 30, 1965, edition of Life entitled: Drama of Life Before Birth. The front cover of the magazine told of an “unprecedented photographic feat in color.” Although, Nilsson’s photographs were not the first of a child in the womb, this was the first time such images had appeared in the mainstream press, and to such a high technical and visual standard. They caused a furor. Within days, the magazine’s entire print run of 8 million had sold out. Shortly after, the images were appearing across the pages of other news titles all around the world.

The photographs featured in the Life article, together with other similar images shot by Nilsson, formed the basis of his 1965 book in Swedish, Ett barn blir till. An English language edition soon followed entitled: A Child Is Born: The drama of life before birth in unprecedented photographs. A practical guide for the expectant mother. Eventually, the book was published in over 40 countries, going on to become one of the best-selling illustrated books of all time. In the end, the images of the unborn children featured came to be iconic, by the late 1970s, they were being sent into space aboard NASA’s Voyager space probes.

Nilsson’s career too had been launched into its own stellar space by the success of A Child is Born; he was showered with professional accolades. Although in later years when asked about his methodology in sourcing the original images for that book, his replies proved vague, even if the preface to the 1965 Life article had been less so. The text to accompany that photo essay states that many of the embryos pictured “had been surgically removed for a variety of medical reasons.”

Increasingly, as the years passed, the pro-life movement appropriated some of Nilsson’s images. Nilsson however, refused to be drawn on the issue of abortion. In one interview, he gave the following reply when asked about that subject: “It depends on yourself. I’m just a journalist telling you things.”

As much as the images were used to advance an anti-abortion argument, however, in a very different way, they also came to be used by radical feminists who wished to promote “abortion rights.” Ironically, their contention was that the images were of the dead, not the living. Furthermore, they claimed the images had been photographically glossed, and, thus, had been invalidated for any use in arguments on abortion. There is some justification to the claims about the manipulation of the figures in the images. The original Life text says as much: “star-like spots around the amnion are merely bubbles in a fluid the photographer has used to support the amnion.” That said, the subject, whether living or dead, remains what the eye beholds: the image of another human being.

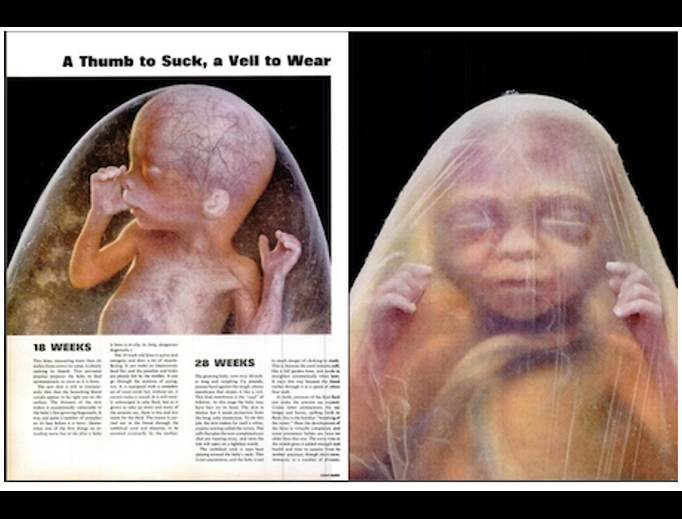

Perhaps this is nowhere more the case than in the image of an unborn child approximately 18 weeks old, contentedly sucking its thumb while apparently asleep in its mother’s womb. Studying the photograph more closely, one sees the child’s hands are fully formed; its nails are clearly visible, its eyelids are closed, its face at peace. Even today, half a century after the photograph was taken, there is a gentle beauty about the image that is difficult to define. Unquestionably, this is in part due to the universal awe felt at the mystery of life incarnated during a pregnancy. Doubtless, however, it is also due to the powerless dependency of the child in the picture. The next picture in the sequence is of an unborn child 28 weeks old. It is described as wearing a “veil.” All the more poignant still as it is claimed that these children in particular were late-term abortions from a Stockholm clinic. Looking at that image now, one realizes what is being worn is a funeral veil.

Knowing the fate of the subjects in these photographs, it makes it harder to gaze upon them without an overwhelming sense of sadness. For those of us born in the 1960s, it is sobering to realize that our journey to life was contemporary with that of the unborn children whose images remain encapsulated forever in A Child is Born, but whose own passage to life, as it turned out, was truncated. That haunting image of the unborn child sucking its thumb is ultimately a photograph record of its subject’s life story complete: one as beautiful as it was tragic.