New Book by Paul Kengor Sheds Light on Diabolical Side of Karl Marx

“Thus Heaven I’ve forfeited, I know it full well,” Karl Marx wrote in a poem in 1837, a decade before his Manifesto. “My soul, once true to God, is chosen for Hell...”

THE DEVIL AND KARL MARX: COMMUNISM’S LONG MARCH OF DEATH, DECEPTION, AND INFILTRATION

By Paul Kengor

TAN Books, 2020

461 pages, $29.95; hardcover

To order: EWTNRC.com

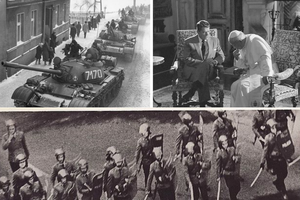

There are three major divisions to this book: Karl Marx’s engagement with Satanism and the occult; the history of Marxist infiltration of churches, Protestant and Catholic; and the contemporary mutations of Marxism from a primarily economic to primarily cultural force for “revolution.”

We know Marxism opposed religion, but Paul Kengor makes clear its founder was influenced not just by theoretical considerations, even if “Marx’s musings about the prince of darkness is a subject avoided like the seven plagues by his aficionados …” (p. 35), despite being clear in his literary output. (Besides being a bad economist and philosopher, Marx was also a bad poet and playwright). There “are certain images that constantly recur in Marx’s writing, such as death, torture, executioners, mutilation, even ruptured wombs, as well as the ferocious manner in which he blistered his enemies with gutter language and vicious words” (p. 77). If by one’s fruits one shall know them, Marx’s are toxic.

Kengor also plumbs congressional testimony about the effort of American Communists, especially in the 1930s and 1940s, to infiltrate Christian churches, primarily by seeding Marxists in strategically located church positions like seminaries and leadership slots to influence or at least dupe others. Quality, not quantity, mattered: The critical mass needed to control the narrative was not numerically high. “It is an axiom in Communist organizational strategy that if an infiltrated body has 1 percent Communist Party members and 9 percent Communist Party sympathizers, with well-rehearsed plans of action, they can effectively control the remaining 90 percent …” (pp. 274-75). He highlights the role of Venerable Fulton Sheen in exposing (and converting) several Communist operatives.

Finally, Kengor explains how yesterday’s economic Marxists have transmogrified into today’s cultural Marxists, advancing “critical theory” in culture-forming institutions like schools and media. If “transformation” did not come from overthrowing the economic order, perhaps it could come from overthrowing the moral and cultural order.

“Cultural Marxists understand that the revolution requires a cultural war over an economic war. Whereas the West — certainly America — is not vulnerable to a revolt of the downtrodden trade-union masses, it is eminently vulnerable when it comes to, say, sex or porn. Whereas a revolution for wealth redistribution has been unappealing to most citizens of the West, a sexual revolution would be irresistible” (pp. 387-88).

Critics may claim Kengor makes connections that really don’t exist or engages in guilt by association, but he is on to something. The one commonality Marxist revolutionaries — of economic or cultural stripe — is their demand for “transformation.” Behind it stands a common assumption: that there is no constant human nature, nothing stable much less transcendent in man, but that he is infinitely malleable to the latest ideas or fads.

The Germans call it Zeitgeist, the “spirit of the times.” Inspired by Hegel, Marxism posits an historical dialectic driving “history forward.” But what (or who) is this Geist that is the historical engine that reduces human beings to successive chronological putty in its hands, and to what end?

I’ve always found Paul Kengor difficult to pigeonhole. A political scientist, his work is historical but goes beyond the purely historical, at least as defined today. On the other hand, St. Augustine plied a philosophy and theology of history that recognized drivers beyond contingent economic, political or cultural actors. Pace the shortsighted who declared Marxism dead and vanquished in 1989, Kengor takes a long view. He thinks in centuries, identifying the common thread rejecting a stable human nature that runs from the scribbler of the British Library through state socialism to today’s “socialists” and “progressives” who proudly sport the bloodstained Marxist label. Thought-provoking.