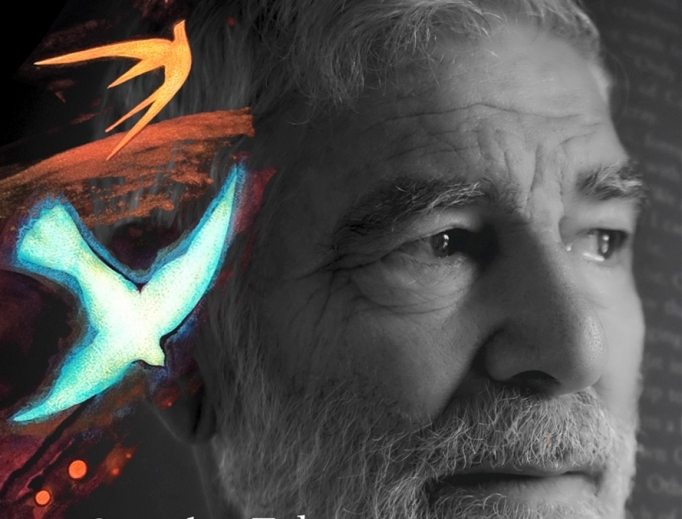

Writer Michael O’Brien and the Mission of Catholic Art

BOOK PICK: On the Edge of Infinity: A Biography of Michael D. O’Brien

On the Edge of Infinity

A Biography of Michael D. O’Brien

By Clemens Cavallin

Ignatius Press, 2019

300 pages, $18.95

To order: ignatius.com or (800) 651-1531

For secularists, suffering is proof enough that God does not exist; or, if he does exist, he has become indifferent to his creation. At the same time, choosing to suffer seems pointless, even fanatical and self-destructive, ruining the only real life we have to live, in the flesh, here on Earth.

For Michael O’Brien, the 71-year-old Catholic Canadian painter, writer of icons and writer of novels,and works of nonfiction, human suffering is at the heart of his art — a condition to be understood as an alignment with Christ on the cross and his resurrection. It is to see the story of every person as the story of Christ.

As we learn in On the Edge of Infinity, a just-released and welcome biography of Michael O’Brien by Swedish author Clemens Cavallin, the Canadian artist knew from the start that his artistic vocation would be a supreme struggle not only for him but his also for his wife, Sheila, and their children.

Cavallin makes clear that O’Brien had many opportunities to cash in if only he turned his paintbrush and pen to more palatable themes without all that uncomfortable Christian imagery.

This single-mindedness came with a high emotional cost — never being sure where the family would live or how they would pay their bills.

In the 1980s, in the town of Mission, British Columbia, the family truly hit bottom. The car was dead and their home was a church basement lent to them by a good priest.

The family became dependent on the Poor Clares for food. But with no car it meant Michael had to push a wheelbarrow up a hill to fetch basic foodstuffs so his family would not go hungry. So humiliated was O’Brien by this experience that he covered the food with a tarp so neighbours would not see how far he and his family had fallen.

Yet, even from this lowly position, he was able to renew his promise to God.

“At Mass in the chapel, Michael felt a presence before him as he prayed; it was in interior image without form, as if a messenger were waiting to bring something from him and to deliver it to the Father,” Cavallin writes. “Michael wondered if this was an ‘angel’ — anyway, he placed in the hands of the messenger the promise that with all his being he would serve God and not mammon.”

O’Brien has produced myriad icons and other works of art. To date, he has written 14 novels, as well as nonfiction books and numerous essays.

Ignatius Press published Strangers and Sojourners, in 1996, a book he had been writing and rewriting for 18 years. From that point on his novels began to flow outward at a swift pace.

What this biography shows is how much of O’Brien’s own suffering, and that of Christ, was imbued in his characters.

In Sophia House, a Polish Catholic, Pawel, struggling with his faith and the direction of his own life, ends up hiding a young Jewish boy, David, who has escaped the Warsaw Ghetto in the Second World War. There is the constant threat of the camps and death for the two of them.

Yet under that horrendous pressure they become spiritual kin, crossing deep religious boundaries.

Young David survives the Holocaust, and we meet him again in Father Elijah as a convert and Catholic priest, dealing with the potential global victory of evil

In Island of the World, which many consider his masterpiece, we see his love for Catholic Croatia and its struggles through the Second World War and then under communism. The story is told through the eyes of Josip, who as a child witnessed the slaughter of his family and village by communist partisans. We follow Josip’s life as he seeks meaning in the shadow of the cross and the hammer and sickle.

Today, O’Brien and his wife live in Combermere, Ontario, 118 miles west of the nation’s capital of Ottawa, in the stunning Madawaska Valley. After all the wanderings of the O’Brien clan, ending up there seems providential. It is also the home of Madonna House Apostolate, a holy community of laymen and laywomen and priests. To live in this region is to literally breathe Catholicism, something of a dream for the O’Brien family.

We should all be thankful for his landing in a holy place. He has sacrificed much to give us Catholic art that is so needed in these times of darkness and confusion.

As Dostoyevsky wrote: “Beauty will save the world” — and as Cavallin’s book makes abundantly clear, Michael O’Brien is doing his part to help in that salvation.

writes from Toronto.