Newman’s Witness: Holiness Amid Secularism

BOOK PICK: Holiness in a Secular Age: The Witness of Cardinal Newman

Holiness in a Secular Age

The Witness of Cardinal Newman

By Father Juan Vélez

Scepter Publishers, 2017

206 pages, $18.95

To order: scepterpublishers.org or (800) 322-8773

When young John Henry Newman experienced his first conversion to an evangelical form of Anglicanism, he was inspired by two maxims of Thomas Scott. One of them — “holiness rather than peace” — became a motto for the rest of his life.

In this introduction to Blessed John Henry Newman’s example of pursuing holiness in 19th-century England as it was becoming more secularized, Father Juan Vélez guides readers through Newman’s life, projects and published works. He presents Newman as a man of faith evangelizing a world that was moving away from Christian doctrine and morality.

After a succinct survey of Newman’s life, including his leadership in the “Oxford Movement,” his conversion to Catholicism, his foundations of the Oratory of St. Philip Neri in England and the short-lived Catholic University of Ireland, and his struggles and eventual acceptance within the Catholic Church in England, the author addresses a number of themes in Newman’s life.

He starts with friendship. Newman chose the motto Cor ad cor loquitur (“Heart speaks to heart”) when he was named a cardinal, and Father Vélez shows how Newman loyally and affectionately shared his heart with his friends.

Chapters on “Holiness and Christian Life,” “Meditation and Study of the Scriptures” and “The Moral Life in the Kingdom of God” offer well-selected passages from Newman’s great Parochial and Plain Sermons. Throughout the book, the author uses quotations from Newman judiciously and effectively; it can be hard to resist Newman’s eloquent prose.

A most appropriate chapter in a book referencing a “Secular Age” offers Newman’s insights into “A Christian Vision of Pursuits in the World.” Newman provides guidance for the laity to infuse our activities at work, in our families and in our social and political life with our pursuit of holiness. The laity has a role in the world beyond a cloistered retreat, and as a priest of the prelature of Opus Dei, Father Vélez warms to the subject of holiness in ordinary life.

Two rather technical chapters follow, as Father Vélez describes the theory of the “Development of Christian Doctrine” that eased Newman’s way into the Catholic Church and examines Newman’s contacts with figures of authority in the hierarchy, which were not always easy. Although Newman was obedient, he was sometimes frustrated by the obstacles and disappointments he faced in various projects. After discussing Newman’s views on marriage and celibacy — he determined not to marry before he became an Anglican minister — the author turns to the heart of Newman’s work in the world, both as an Anglican and Catholic: education.

Chapters on “The Christian Gentleman,” on university education, and on Newman’s so-called “Catholic Eton,” the Oratory School, demonstrate that Newman, from his days as tutor and fellow at Oriel College in Oxford and his rectorship in Dublin to his day-to-day involvement with the Birmingham Oratory, emphasized the moral and spiritual aspects of education as well as the pursuit of intellectual and philosophical excellence.

As Father Vélez aptly summarizes Newman’s view, acknowledging the limitations of academic study and a liberal arts education, “Reason is not the same as virtue. Knowledge contributes to make men better, but it does not replace religion ...” in forming good Catholic Christians (131).

Newman and Charles Darwin were contemporaries, and Father Vélez reminds us in Chapter 14, “Faith, Reason, and Science,” that Newman saw no conflict between faith and science. He accepted the scientific theory that Darwin proposed, finding no difficulty in reconciling God’s creation with evolutionary development. Newman stressed — in connection with scientific education and experimentation — that the Church is never afraid of the truth because she teaches and defends the truth. Father Vélez describes, very accessibly, some of Newman’s theories from The Grammar of Assent of how we gain certitude and knowledge, which cannot always be obtained by scientific experimentation or syllogistic reasoning, but by intuitive reasoning backed up by experience and observation: It is reasonable to accept truths on faith.

Perhaps the only chapter that disappointed was “Ecclesiology and Converts.” As a convert himself, Newman often counseled Anglicans who were thinking about becoming Catholics. Of course, he believed that the Catholic Church is the “one true fold of Christ,” and he wanted to call everyone to that fold, but Newman was also concerned that converts be ready to assent to all the teachings of the Church, to have counted the costs to them — and he thought that the Church needed to be prepared for receiving them as much as they for the Church.

Father Vélez too often uses the term “Roman Catholic,” which was used in England in distinction to Anglo-Catholicism, the High Church ritualist party in the Church of England. Outside of that context, however, “Roman Catholicism” ignores the diversity of rites and traditions in the Catholic Church (the Eastern-rite Catholics). I was surprised that Father Vélez did not comment on the personal ordinariate established by Pope Benedict XVI as a fulfillment of Newman’s concerns, especially since the groups of Anglican converts in England are organized in the Personal Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham with the spiritual patronage of Blessed John Henry Newman.

In the final chapter, the author describes the development of Newman’s devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary, distinguishing his restrained English style of prayer to the Italianate “excesses” of Father William Faber and others. Nevertheless, Cardinal Newman loved Our Lady and pointed out “that all the dogmas about the Virgin Mary serve to teach us about the divinity of Christ.” For example, Newman defended the dogma of the Immaculate Conception, noting that she is “the Second Eve” (188).

Overall, Father Vélez presents cogent evidence that Newman “stands as a credible witness to holiness in a secular age” by responding to the “rationalism and materialism” and the “growing agnosticism and atheism” of the 19th century in ways prophetic to us today (191).

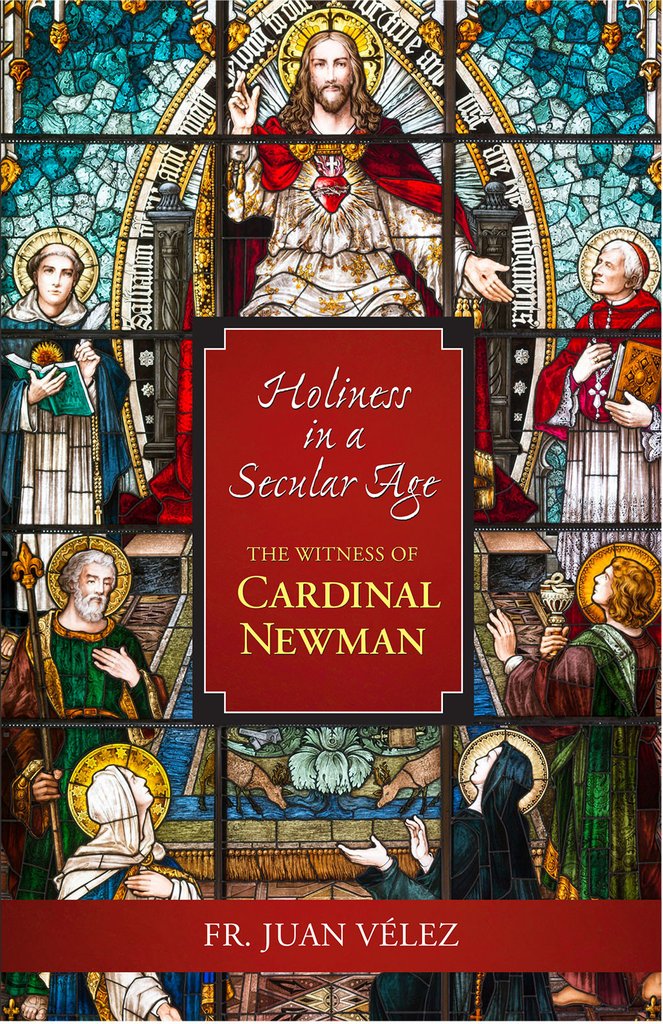

This volume is well illustrated with images of Newman, his family and friends, and locations connected with him in England and Ireland. The cover, featuring a detail of the stained-glass window in the chapel of the St. Thomas Aquinas Newman Center at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, is exquisite.

The reader unfamiliar with Newman could have no better introduction to this great modern witness to the Catholic faith; the reader familiar with his life and works will appreciate many of the author’s insights.

This excellent biography will lead readers to further knowledge of Blessed John Henry Newman, whose canonization, as the back cover attests, is imminent.

Stephanie A. Mann writes

from Wichita, Kansas.