Young People Hunger to See the Face of God — Don’t Starve Them with Emoji Religion

If the deposit of faith is cast away, what is left but shallow emotion?

As a freelancer, I get to work with a wide variety of educational providers and leaders. I learn a lot and the diversity of thought provides fertile ground for my own ideas — and keeps me honest!

Recently, I was on a project to revamp an existing Catholic religion curriculum for online and hybrid learning. The training session covered student assessment, and the required assessment tool for my particular assignment was the “multiple-choice emoji.”

I had to ask for clarification, never having encountered such an assessment mode except in jest.

The goal, I was told, was to “check in” with the students on their feelings about the course material. You could, for example, have a question asking, “How do you feel about the Mass?” The child could choose a happy face emoji, angry emoji, sad emoji, or green/sick emoji. If the child picked the happy face, all was well. If the child picked another, then the teacher would know that he or she should “check in” with the child on their religious progress.

The assessment tool seemed at odds with the provider’s stated goal: to make the course as rigorous as the other subjects for which the company was known. The underlying reasons for choosing a feelings-based assessment became quickly evident, however, when I started watching the course video content.

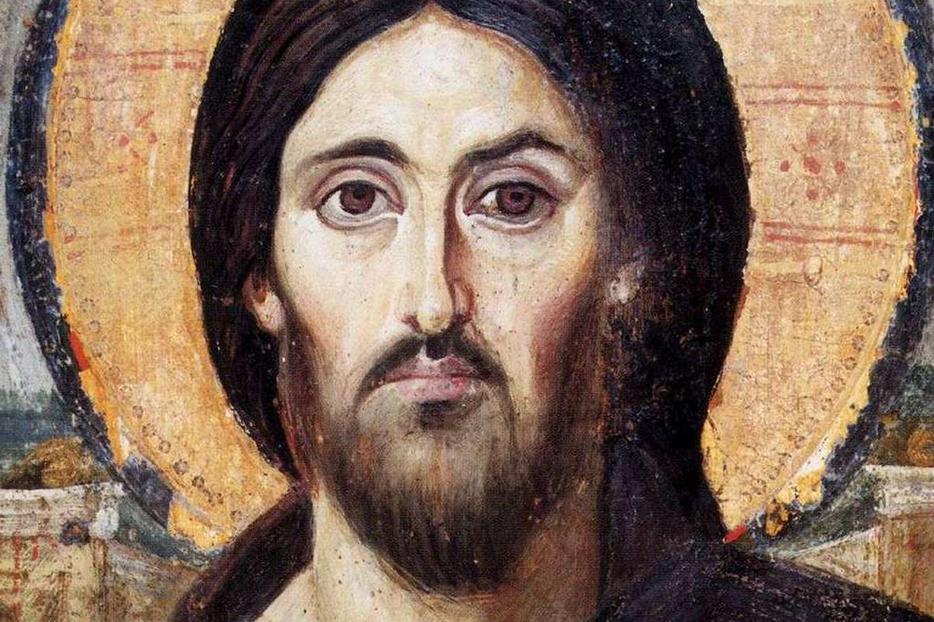

Neon Muppet-like characters (but not as good) leapt around the screen, frenetically singing in Elmo-imitation voices about God’s love. In others, cartoon Jesus waved his hands like a robot, while the narrator chirped out his teaching: Be nice!

About a third of the videos were produced by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and they explained that Jesus was a “special man” with an important mission. The Eucharist was presented as a way Jesus gave us to say “thank you” to God. Communion is a meal, and we feel happy about it. Sprinkled in were a few EWTN shorts, which at least provided some traditional prayers: the Our Father, Hail Mary and Glory Be.

The experience was eye-opening, and I understood the reason for the emoji-based assessments. If there is no deposit of faith, what is left but emojis?

I do not blame anyone involved in the company — not one of my supervisors was Catholic. And at this point, blame doesn’t help.

But we must correct this vision of “religion class.” If the largest provider of online religious instruction for Catholic schools has been using primarily Mormon materials and a “faith is a good feeling” mentality, something is seriously wrong.

Religious instruction should require as much intellectual rigor as we would expect for our natural science, mathematics or language arts classes. Religion is not the “easy subject,” but it is the queen of the subjects that ties all the others together.

Even a small child deserves a compelling and deep education in the truths of the faith, the stories of Scripture and the joy found in living the commandments of God and of his Church.

I went back and began weeding out the non-Catholic sources and re-directing teachers to videos produced by Catholics. But the entire course needed re-ordering: and what better order than that used by every Catechism written since St. Thomas Aquinas? Taking the Catechism of the Catholic Church as my outline, I started from the beginning.

A young child is even more able than his adult teachers to perceive the truths of the Faith, and less able to assess their own feelings. So begin with what they know: themselves. Not, “how do you feel about God?” But give them something to know: Who made you? God made me.

This is not a feeling. This is not an emoji. This is the fact of life, living and true. Whatever the child’s emotions, home life, sufferings, talents or struggles, he will always be able to cling to this fact: God made me.

Next, who is God? Who is this One that made me? The child naturally loves nature, so take them outside. Show them the river, lakes and beaches. Show them trees and stars. Tell them the story of Creation.

Is this God good? The child will enthusiastically conclude: Yes, God, who made me, is good. I love his works. Your emoji today may be sad, angry or happy. But God is good.

From there, proceed to knowledge of human beings, questions of why there is evil (the Fall), the redemption, Jesus Christ, Mary, the Church, sacraments, the Commandments and prayer. We owe our children firm foundations in the truth, a clear connection between all the truths of the faith, and the quiet confidence that whether we feel it or not, God is love. Love is truth. And truth is freedom.

The assessments can also be based on comprehension of the truths: There is nothing wrong or emotionally-stunting about being required to memorize the Apostles Creed or the Two Great Commandments. Allowing teachers and parents to assess mastery of the truths of the faith helps them pinpoint areas of confusion (There are three Gods! Mass is a party!) gently, early and with good humor. Masking these confusions by focusing solely on a child’s feelings forms future adults who simply don’t see the point of doctrine or attending Mass. Which is precisely where we are today.

There is absolutely a place for reflecting on ourselves and our emotions. My dear psychologist friend points out studies indicating that emoticons and emojis, in spite of their convenience, actually obscure human communication about feelings. Particularly for children who are just learning to articulate their feelings, emojis in practice limit the range of possible reactions to an image or statement.

The restrictive “Are you happy, angry or sad?” question oversimplifies the complex range of emotions between “elated” and “despondent” so that children are habituated to oversimplify their reactions. The better way to help a child connect with their feelings is to give them the true, the good and the beautiful in clear, loving and attractive ways so that their feelings are properly habituated and allowed to function in a wide range, even if they cannot name the emotions they are feeling. This is done most effectively through personal relationships with parents and teachers, who love the child unconditionally no matter what emoji he or she picks for a picture of God the Father.

Emojis are fun. Emojis are cute. But they do not train children to feel happy about God. Nor do they equip them to live, preach and love the Catholic faith.

- Keywords:

- doctrine

- catechesis

- deposit of faith

- mysteries