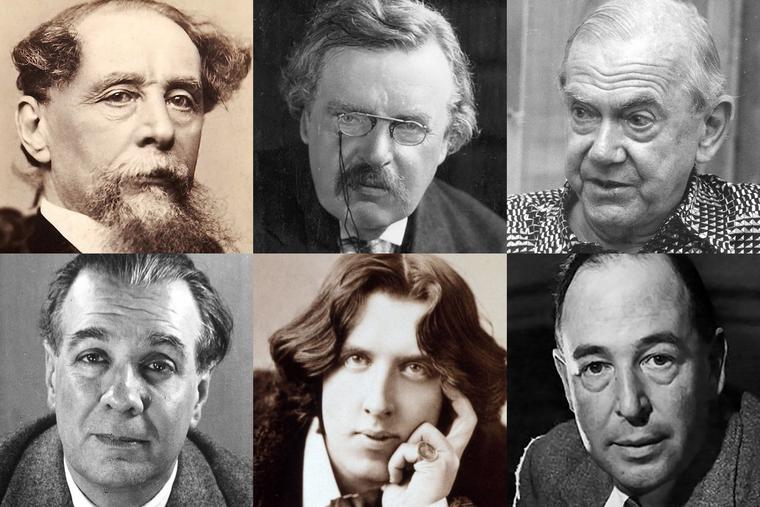

A Handful of Authors — Dickens, Wilde, Lewis, Borges, Greene

Dickens, Wilde, Lewis, Borges and Greene have very little in common, yet they are all held together by the thin thread of Chestertonian brilliance.

There is something a little eclectic about the theme of this issue. Whereas themes are usually cohesive and coherent, focusing on an individual writer or an individual nation, or on specific periods or genres, this issue is a loosely assembled “handful” of authors who would appear to have little or nothing in common. There is a good, if somewhat mundane and prosaic reason for this. We’ve been sitting on these articles for some time wondering how we could make them fit into a future theme. In the end, a combination of impatience and pragmatism led to the decision to bring them together, even though there was no obvious thematic “glue” to connect them.

Since this is so, I thought I would stitch our handful of authors together with a Chestertonian thread, connecting them in the light of what G.K. Chesterton said about them or what they said about G.K. Chesterton.

Taking our five authors in chronological order and beginning with Dickens, we can connect Chesterton with his Victorian predecessor in terms of the two books that Chesterton wrote on Dickens. These are his biography (of sorts), Charles Dickens, published in 1906, and his Appreciations and Criticisms of the Works of Charles Dickens, published five years later.

“Dickens was a mythologist rather than a novelist,” Chesterton wrote. “He did not always manage to make his characters men, but he always managed, at the least, to make them gods.” It was the presence of the essential goodness in man, the imago Dei, which Dickens depicted and with which his readers resonated. “In everybody there is a certain thing that loves babies, that fears death, that likes sunlight; that thing enjoys Dickens.”

Chesterton was much less sympathetic with the very non-Dickensian grotesquerie of Oscar Wilde but was nonetheless greatly influenced by it. His experience of the atmosphere of Wildean Decadence when he was a student at the Slade School of Art in the early 1890s is grimly evident in “The Diabolist,” an essay which recounts his short-lived acquaintance with a morally iconoclastic young man who might have stepped out of Wilde’s novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray. Like Wilde, and possibly as a mark of Wilde’s influence, Chesterton used the power of paradox to great effect. This is evident in his finest novel, The Man Who was Thursday, which can be seen as a riposte to Wilde and the Decadent diabolism of the fin de siècle. Whereas Wilde has stripped the masks off reality to discover the darkness lurking beneath the façade, Chesterton stripped the masks off reality, represented by the anarchists in the novel, to discover the light of goodness, truth and beauty within reality itself.

The remaining three authors who form the focus of this issue were not influencers of Chesterton but were influenced by him.

C. S. Lewis was an atheist serving in the British Army during World War One when he first read Chesterton. To his surprise, he couldn’t help liking Chesterton, stating that, despite his Christianity, GKC had more common sense than all other modern writers. A few years later, upon reading The Everlasting Man, Chesterton’s rebuttal of the historical revisionism and chronological snobbery of H.G. Wells, Lewis wrote that Chesterton had explained the Christian outline of history in a way that made sense. In Surprised by Joy, Lewis’ account of his conversion to Christianity, he acknowledged Chesterton’s key role on his journey towards belief.

Jorge Luis Borges also confessed an admiration for Chesterton, describing him as a “genius” and “a great poet” who had been neglected and dismissed because of his Catholicism and, in consequence, was not as well-known as he should be. “Chesterton was a great writer, of course … a man of genius, but people think of him in terms of his opinions, and that is wrong.”

As an admirer of Chesterton’s epic poem, The Ballad of the White Horse, Borges admired the way that Chesterton expressed ancient metaphors “in a new way” in the poem: “What Chesterton has done is give a new shape to those very ancient and, I should say, essential metaphors.” He said that his own short story, “Streetcorner Man,” was “written under the triple influence of Stevenson, Chesterton and Josef von Sternberg’s unforgettable gangster films.”

Borges was also a great admirer of Chesterton’s Father Brown stories, describing them as “wonderful”:

They are many things at the same time. … [T]hey are detective stories, they are parables, and they are poems, also. But perhaps when the detective novel has died out, and it will die out in due time, those books will be read for what is fantastic in them. As I say, not for the solving of the puzzle, for the puzzle itself.

The final author in our loosely connected “handful” is Graham Greene, whose conversion to Catholicism was due in part to Chesterton’s influence. Throughout his life, Greene continued to read and admire Chesterton’s work. Describing Chesterton as “another underestimated poet,” Greene compared him favorably to T. S. Eliot: “Put The Ballad of the White Horse against The Waste Land. If I had to lose one of them, I’m not sure that … well, anyhow, let’s just say I re-read The Ballad more often!”

Dickens, Wilde, Lewis, Borges and Greene might be a handful of authors with very little in common, as different from each other as could be imagined. Yet we can see that they are all held together by one thin thread of Chestertonian brilliance. Such is the indomitable genius of the great GKC.

This essay first appeared in the St. Austin Review and is republished with permission.