A Good Shepherd Lays Down His Life for the Sheep

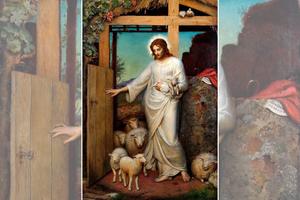

SCRIPTURES & ART: The image of the Good Shepherd is an ancient and rich one, theologically and artistically.

The Gospel of the Fourth Sunday of Easter (John 10:11-18) always focuses on the Good Shepherd. The reading is actually found in John’s Gospel, sandwiched between two miracles we read about during Lent: the healing of the man born blind (March 14) and the raising of Lazarus (March 21). Just before the latter and right after Jesus calls himself the “Good Shepherd,” he is the victim of a lynch mob that tries to “seize” him (John 11:22-42).

If all that clashes with our image of a “good shepherd,” our image needs adjustment. Good shepherds just don’t walk around vacant-eyed, saying nice things, and cuddling lambs. As Jesus tells us in the Gospel, the “good shepherd” puts his life on the line for his sheep. Whether it be the native lack of ovine intelligence that gets them lost or their various predators (wolves, birds of prey, other wild animals) lurking for them, sheep need aggressive protection. They repay their shepherd, in turn, with loyalty and obedience.

The good shepherd is one who owns and gathers the sheep. Note both verbs. The good shepherd is personally invested in his sheep because they are his sheep. The relationship is not just the result of a job; it is deeper than that. The good shepherd also gathers the sheep. He is responsible for creating order among the sheep and in the sheepfold. He leads them; he does not just accompany them on whatever path they feel inspired to follow. Not only does he lead them, but he leads them “to pasture,” i.e., to good food, which is why St. Peter is thrice commanded by Jesus to “feed” and “tend my sheep” (John 21:15-19).

Jesus knows that he is the model Good Shepherd. He knows that shepherding is part of his Davidic line: David was literally called out of the fields by Samuel to be anointed Israel’s great king (1 Samuel 16:11), a fact of which God often reminded David when he forgot who was really in charge (Psalm 78:70; 2 Samuel 7:8). Long before Jesus speaks of what a bad shepherd does, Ezekiel did (34:1-10). The great prophet described the shepherds who fleece the sheep, fail to feed them, care for them, or search them, allowing them to wander pell-mell “on all of the mountains, on all of the hills.” Such shepherds the Lord intends to dismiss (34:10) when he reclaims “my sheep” (note the personal element, as indicated above).

Ezekiel (34:11-30) also prophesies about the coming “good shepherd.” He will tend, feed and heal the sheep. He also intends to “judge” the sheep, distinguishing between the “sheep and goats” and between “the fat sheep and the lean sheep,” i.e., those that abuse others and those abused. That shepherd will be David, but since Ezekiel is writing at least 400 years after David, he is referring to the Davidic line. This figure is Messianic: He will “eliminate wild beasts from the land so [the sheep] can live securely in the wilderness and sleep in the forests” (v. 25). (Recall this year’s Markan Gospel of the Temptations of Jesus, which specifically alluded to his being “in the desert with the wild animals?” — Mark 1:13). He will smash the “bar of their yoke” (cf. Isaiah 9:4) — our Lord offers a “yoke that is easy” (Matthew 11:30). They will learn that “I, the Lord their God, am with them” (v. 30). “And as for you, my sheep, the flock that I am pasturing, you are mankind and I am your God” (v. 31), already foretold in Psalm 23.

Not only is Jesus the Good Shepherd, but he is the sheep. He is “the Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world,” as John the Baptist confessed (John 1:29). He is slaughtered like the Paschal Lamb (Exodus 12:1-13) “whose blood consecrates the homes of all believers” (Easter Vigil), led to the slaughter of the cross (Isaiah 53:7) at the same hour that the sacrificial lambs were slain in the Temple (John 19:14, which is why John specifies the hour that Pilate pronounces sentence on Jesus).

One might be surprised to know that one of the first images of Jesus in Christian art, dating all the way back to ancient Rome, is that of the “Good Shepherd.” Images of the Good Shepherd could already be found in the catacombs, as this Shepherd Carrying a Lamb from the Catacombs of Domitilla suggests.

Scholars date this statue from about A.D. 300-350. That’s a critical span of time, because Constantine legalized Christianity in 313. Before that historic event, however, Christians had to contend for a decade with one of the most vigorous persecutions against them, Diocletian’s, which called for a resurgence of the traditional Roman religion and cults.

Among those cults was the kriophoros cult, the cult of the ram-bearer, associated with the sacrifice of rams to solicit the protection of the gods, especially from plague and pestilence. Those cults, reaching back to ancient Greece, were already about 800 years old by the time we reach the era of Diocletian and Constantine.

The image of the shepherd carrying a sheep did, therefore, have a certain ambiguity. Since persecuted Christians had no public place of assembly, and therefore no permanent structure (a church) to outfit with sacral art, their art found its expression in the catacombs. There the image of the Good Shepherd was both adaptable to the idea of leading the deceased (often martyrs) to heavenly pastures while, at the same time, also being potentially vague enough not to set off immediate alarm bells. It was like the Christian “graffiti” of the fish which, on the surface, looked simply like a fish but the letters of whose name, “Ichythus” also spelled out an early Christian profession of faith: “Jesus Christ, Son of God, Savior.”

Fast-forward a hundred years or so. The illustration above is from the Mausoleum of Galla Placida in Ravenna, northeast Italy. It dates from about A.D. 425, i.e., roughly a century after Constantine’s Edict of Milan granting Christians toleration and roughly 45 years after Theodosius’ Edict of Thessalonica making Christianity the state religion. This is a ceiling mosaic, i.e., made up of tiny tesserae, or tiles, which together create the image.

As one can see, there is no ambiguity here about Jesus as the Good Shepherd. He is clearly grown up and dressed in regal gold and purple with sandals on his feet that none are fit to untie (Mark 1:7). His shepherd’s staff is the golden cross. The fact that the cross is depicted was itself a late development, because Christians — who during persecution lacked no familiarity with the real thing — did not start including crosses in their art until crucifixion had been abolished as a form of capital punishment in the Roman Empire.

Christ’s six sheep — symmetrically split on each side — are well-nourished by the Lord in green pastures (Psalm 23:2). They rest secure, all with their eyes fixed on him, whose own eyes survey the landscape to keep watch with his victorious staff (Psalm 23:4) and whose hand pets one of them. The limited color palette (white, blue, green, earth tones) serves to reinforce the centrality of Christ, both physically centered as well as clad in gold.

The image of the Good Shepherd is an ancient and rich one, theologically and artistically. Many other artists and painters have developed it, some perhaps occasionally in such saccharine ways that we forget the rigors a shepherd must face for his sheep.

- Keywords:

- good shepherd

- Scriptures & Art