Pope Francis Comes to Bosnia Armed With the Gospel

NEWS ANALYSIS: Twenty years after an expedient deal, the Holy Father makes a day trip to an ethnically, culturally and religiously diverse country.

SARAJEVO, Bosnia-Herzegovina — The Holy Father selects destinations carefully.

In Sarajevo, a majority-Muslim city, Pope Francis enters as a geo-strategist with Mark’s Gospel on his lips: “You shall love your neighbor as yourself” (Mark 12:31).

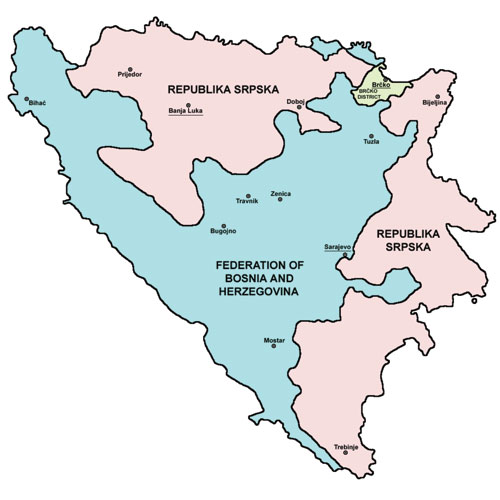

Despite experiencing Europe’s worst war since 1945, fought entirely on ethnic and religious lines — despite a peace settlement making segregation permanent and a constitution that divides the state into unequal parts (Bosniak Muslims and Croats live in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, while Serbians inhabit the geographically awkward Serbian Republic) — regular people instinctively yearn for the normalcy that comes from focusing on shared humanity.

Regular people are Pope Francis’ target audience, people such as Salim Hajderovac, a Muslim woodworker who carved the great chair for Saturday’s outdoor Mass.

“Politicians made us fight each other at the time [of war] but we, the common people, live together, work together, celebrate together and die together,” Haiderovac explained to Reuters.

Historically, Sarajevo was a culturally diverse place not unlike Tirana, Albania, Pope Francis’ first Balkan destination, which he visited last September. The Holy Father described his “great joy” regarding “the peaceful coexistence and collaboration that exists among followers of different religions” in Albania.

In Bosnia, there’s mounting frustration expressed by Church leaders, reflective political figures and people in the streets that a rigid, corrupt state works against prosperity and freedom.

Meanwhile, external actors, especially from Saudi Arabia and Turkey, stand ready to take advantage of local anger, especially in the Muslim community, which represents more than 50% of the population in Bosnia-Herzegovina — although no official census has been taken since 1991.

Disintegration and War

Yugoslavia, a country created in 1918 out of the trauma of World War I, never had a unified national identity.

Communist leader Josip Broz, known as “Tito,” ruled from 1946 until his death in 1980, and his totalitarian regime held the (ostensibly secular) country’s many disparate elements together.

With the collapse of Soviet communism across Eastern Europe in 1989-90 came the gradual, violent dismemberment of Yugoslavia, largely along ethnic lines — an ethnic divide marked by religious division too: Serbs are mainly Orthodox Christians, ethnic Bosnians are mostly Muslim, and the Croatian community is majority Catholic.

The conflict was complex, as it was fought on multiple fronts: Wars in Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia, Kosovo and Serbia are known overall as the Yugoslav Wars of 1991-1999.

More than 100,000 people died as a result. More than 2 million people were displaced, although 1 million eventually returned to their homes by 2004.

Today, all six of the republics that comprised the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (so named in 1963) are independent countries: Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Slovenia, Serbia. Kosovo, an “autonomous province” within the Serbian Republic, declared its independence in 2008.

Bosnian Franciscans

Catholics were both victims and combatants, as most of the Croatian and Slovenian forces were members of the Church.

An example of hatred and destruction unleashed in Bosnia is reflected in what happened at Sts. Peter and Paul’s Franciscan monastery and seminary on the outskirts of Sarajevo.

For two months in the spring of 1992, Serbian forces isolated 14 Franciscan friars and eight sisters in the monastery, not allowing them to leave. On June 8, a Serbian paramilitary group descended on the community, threatening the religious with death and forcing them into the monastery’s basement at gunpoint.

After 30 hours, the Franciscans were released and expelled from the country. The monastery and seminary, including a library with precious manuscripts, were burned. Despite having been active in Bosnia for more than 700 years, the Franciscans were being evicted as foreign interlopers.

How did the Franciscans respond? They immediately rebuilt, on a bigger scale, employing a renowned Muslim architect as evidence that reconciliation was key to the future.

The order initiated St. Anthony’s Bread in 1992 to distribute food, currently serving more than 1,000 people a day.

They created a center for physical therapy, programs devoted to post-traumatic stress disorder, schools for poor children and aid to the elderly. They converted a huge building into a student dorm to keep talented students from disappearing, often for good, abroad.

They started a radio station and developed other media tools.

“The war led us to better organization,” Franciscan Father Mijo Dzolan, provincial superior, told the Register.

Massacre at Srebrenica

Probably the most atrocious event in the Bosnian War occurred in and around the town of Srebrenica, in the northeast, a Muslim-majority town within the Serbian-dominated Sprska Republic.

Bosnian Serb army units began systematically starving the people of Srebrenica in 1992, by preventing any food, medicine or humanitarian aid from entering.

By 1995, the army captured the town, systematically separated boys and men and assembling them in fields, warehouses, schools and soccer fields.

More than 8,000 victims, mostly men, were massacred; more than 6,800 bodies have been identified using DNA analysis and properly buried. At the same time, hundreds of women and girls were raped and sexually abused.

Dutch peacekeeping troops from the United Nations proved wildly incapable of protecting local people. Last year, some were found culpable by the International Court of Justice in The Hague, Netherlands.

The Muslim presence in Bosnia dates back centuries, to 1463, when the Ottoman Empire conquered the kingdom of Bosnia. Traditionally, the community has long practiced a particularly moderate, even mystical, version of Islam.

“In Bosnia-Herzegovina, Islam was always involved in an exchange of ideas with other religions, Catholic and Serbian Orthodox and Judaism,” Enes Karic, a University of Sarajevo Islamic studies professor, told Deutsche Welle.

Days after the Srebrenica massacre, for example, a leading imam, Husein Kavazovic went on the radio to say: “Dear brothers and sisters, these people were killed by Chetniks [ultranationalistic Serbs]. Whoever wants to fight can join the front — but under no circumstances should he take revenge on Serbian civilians who live here or elsewhere. The people in Srebrenica were killed by Chetniks — and not all Serbs are Chetniks.”

Kavazovic was elected grand mufti two years ago, replacing Mustafa Cerić, who had close relations with the Vatican, and led the Bosnian Muslim community from 1993-2012.

Troubling Signs

Widespread anger in 2014 over economic misery, including unemployment around 30%, corruption and a bloated government bureaucracy, resulted in rioting in 20 towns and cities, mainly in the Bosniak-Croat federation. Thousands gathered in the major urban centers of Sarajevo, Tuzla and Zenica. Protesters set fire to government buildings. They tossed furniture and file cabinets from fourth-story windows in Tuzla and torched the presidential residence in Sarajevo.

Calling the situation “disastrous” in a public discussion with Aid to the Church in Need last October, Bishop Franjo Komarica of Banja Luka (in the Serb Republic) outlined the Catholic Church’s strategy: “We need more justice, reconciliation and willingness to work together.”

Cardinal Vinko Puljic of the Archdiocese of Vrhbosna has long pointed to the Dayton Peace Accords, an agreement signed 20 years ago in Dayton, Ohio, by the three main antagonists as the source of the country’s problems.

He once queried, “Divide the country and then pretend it is one nation? This is deeply illogical.”

In an interview with the Italian newspaper Il Giornale earlier this year, the Bosnian cardinal more bluntly pointed to state dysfunction as inhibiting positive growth: “This state does not work.”

He has described at least two other obstacles for the Catholic community: inequality enshrined in the constitution (derived from the Dayton Accords) and the drastic loss of life due to the war.

“The treaty of Dayton was saddening. It was not feasible. It failed. This fact is problematic, because when the Croats were left with no rights, it brought about a great reduction of faithful Catholics in the country,” Cardinal Puljic explained in late 2012.

“Whoever prevents Bosnia-Herzegovina from living its own multicultural reality is making a very big mistake,” he added.

Bosnia-Herzegovina’s Catholic population fell from 820,000 to 430,0000 due to the war. Neighboring Croatia offered full citizenship to displaced Bosnian Croats during the war, and many left for good.

Cardinal Puljic thinks Europe has been more sensitive to the needs of the Muslim community than to the Christian foundation of European culture.

Yet, the longtime Church leader, named cardinal in 1994 by Pope St. John Paul II, described a distinct role for Catholics in ameliorating the “great tensions between Orthodox Christians and Muslims.”

He said, “We Catholics are like catalysts between them. We want to create tranquility” and “a climate of dialogue,” because it’s “necessary to always talk in order to destroy prejudice.”

‘A Gun to My Head’

Ambassador Muhamed Sacirbey signed the Dayton Accords on behalf of the Bosnian Muslims, then withdrew his signature in 2005 based on the framework’s post-war impact on the country.

In a 2010 interview with Euronews, his observations confirm Cardinal Puljic’s.

Describing the agreement as being “imposed” by the “big powers,” the statesman says he signed because “I had a gun held to my head.”

He explained, “We were told we had to accept voting and representation in office along ethnic lines, and that’s why Dayton is failing over the long term. You are embedding, I emphasize the word embedding, ethnic politics, so there will be an ever greater appeal to chauvinism.”

It’s a foundation for peace, it’s certainly a foundation for ending the war, but it’s no foundation for any normal country, said Sacirbey.

“I think, in fact, Dayton is still the root of what is wrong with Bosnia,” he added. “It stopped the war, but it is not in fact, the final, lasting basis for the country to prosper.”

Wahhabi Influence?

One of the most startling aspects of touring Bosnia-Herzegovina is the presence of new and renovated mosques at every turn.

Most of the new construction contrasts sharply with traditional Ottoman stone mosques, with low, rounded domes and a single monumental minaret. Many of the new ones were built with Saudi money, following a particular branch of Islam, Wahhabism.

Wahhabi Islam is an 18th-century development of Sunni Islam practiced today mainly in Saudi Arabia. The Islamic State (ISIS) draws inspiration from the Wahhabi claim that Islam should determine and dominate politics and government.

The European Parliament declared in July 2013 that Wahhabism is the primary source of international terrorism.

The influence of Wahhabi Islam in the Bosnian Federation is real, imported by foreign fighters who came during the war to fight with the Bosniak Muslims and never left, and financed by Saudi charitable foundations looking for spiritual protégées.

Its most overt manifestation in Sarajevo is the King Fahd mosque, the biggest Muslim holy place in the Balkans (it can accommodate 4,000 worshippers), built by the Saudis in 2000 at a cost of about $30 million.

The mosque sits on property owned by the Saudi government. According to an ABC News report, a Bosnian investigative reporter concluded the Saudis spent about $500 million between 1992 and 2001 building mosques in Bosnia.

“Islam is a complex family,” Dzevad Karahasan, a Bosnian Muslim teacher at the Franciscan Theological Seminary, explained to the Register. “Wahabbism is an absolutely new phenomenon in Bosnia today: unknown; imported.”

The teacher added, “Muslims in Bosnia don’t go to the new mosques. They were built by people from the outside. The traditional mosque in Bosnia is small, like a house.”

Across Muslim Bosnia over the last 10 years, there have been clashes between the moderate local community and outsiders with more radical assumptions about Islam and its role in Bosnia-Herzegovina.

In 2011, when a Bosnian national, said to be associated with Wahhabism, opened fire on the U.S. Embassy in Sarajevo, condemnation was swift.

The gunman and some 17 others were arrested quickly.

Bosnian Muslims fiercely rejected his actions. The grand mufti condemned the shooter declaring, “The attack on the U.S. Embassy is an attack on us.”

Yet many fear the region’s miserable economic picture, combined with external support. is making extremist religious practice more attractive.

A National Public Radio piece on the phenomena in Kosovo quoted a reform-minded politician as saying $800 million had been invested by Middle-East charities in developing support in the tiny, impoverished country.

“Radical Islam is, mid- to long term, one of the biggest dangers for Kosovo, because they are aiming to change our social fabric,” Ilir Deda told NPR.

Last October, Bishop Franjo Komarica of Banja warned, “There are people here who could exploit the instability.”

“We mustn’t ignore the dark clouds arising to the southeast. Destructive, radical forces from the Arab world can very easily settle and flourish here,” he said.

Mosque Diplomacy

Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia’s emerging rival for global leadership in the Islamic world, the Turkish government, under President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, also sees an opening to influence the future of Bosnia-Herzegovina.

The Turkish media has deemed it “mosque diplomacy,” and it involves courting Muslim communities in former Ottoman lands through investments in schools, cultural landmarks and economic partnerships.

The restoration of traditional Ottoman mosques in Bosnia-Herzogovina and Kosovo is one such activity pursued by Turkey’s Religious Affairs Directorate (Diyanet) and the Turkish Cooperation and Development Agency.

Not to be outdone by the huge King Fahd mosque in Sarajevo, the Turks are building an even bigger mosque in Tirana, to accommodate more than 4,500 worshippers, at $34 million.

According to professor Istar Gozaydin of Istanbul’s Doğuş University, in an interview with Voice of America, the Balkan countries, especially Bosnia-Herzogovina, are the main field of competition between Turkey and Saudi Arabia in terms of shaping the future of Islam.

What Pope Francis’ visit is designed to do is to afford him multiple opportunities to encourage local people in Bosnia-Herzegovina, of all faiths, to overcome rivalry, resist external pressure and collaborate with each other constructively.

A Reuters article last week, titled “Pope Visit Preparations Promote Unity in Multi-Faith Bosnia,” described exactly that outcome in the lead-up to Pope Francis’ day in Sarajevo.

Victor Gaetan writes from Washington.

He is a contributor to Foreign Affairs magazine.