Centering Catholic Theology on the Person of Christ

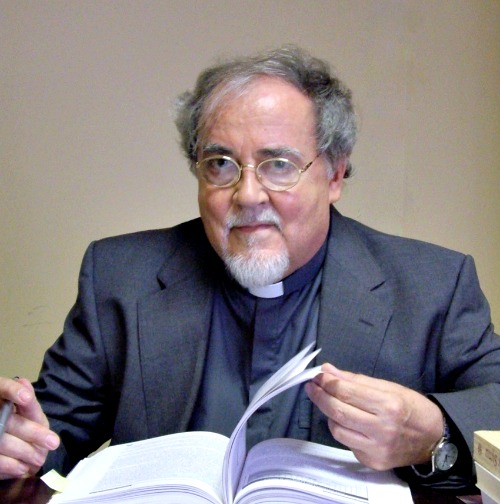

Father Reál Tremblay, the new president of the Pontifical Academy of Theology, discusses his theological approach and his memories of studying under the direction of Joseph Ratzinger.

VATICAN CITY — Pope Francis last month named Redemptorist Father Réal Tremblay president of the Pontifical Academy of Theology. He is professor emeritus of fundamental moral theology at the Alphonsian Academy.

Born in Metabetchouan, Quebec, Canada, Father Tremblay was a student of Joseph Ratzinger in the 1970s and earned his doctorate in dogmatic theology in 1975 from the University of Regensburg, Germany.

The Pontifical Academy of Theology was founded in Rome and received its first statutes from Pope Clement XI in 1718. Its mission is to promote dialogue between faith and reason and deepen Christian doctrine, following the indications of the Holy Father. It also aims to better understand revealed truth and its presentation to men and women of today, so they might receive the message of Christ and incarnate it in their own lives and their own cultures.

In this email interview with the Register, Father Tremblay discusses the challenges of theology today, recalls his memories of studying under Joseph Ratzinger and shares his thoughts on the upcoming Synod on the Family.

Father Tremblay, how do you see your main tasks as president of the Pontifical Academy of Theology?

While the “tasks” are defined by the statutes of the academy, the program (which corresponds more, I think, to the meaning of the question) concerns the way in which one responds to “tasks.”

For the moment, I do not have a clearly defined program for the next five years of my mandate. This will be done (in continuity with the work done in the past) in the fall with the help of the Council of the Academy.

But I have in mind certain ideas which I would like to mention now. For example: to promote a theology that is capable of helping people to rediscover the greatness and beauty of a Christianity centered on the person of Jesus and help to live in joy. So, not a speculative theology for the sake of speculation, but a demanding theology, always in contact with the life of people and the questions that it poses. This naturally implies a good knowledge of the world today in its most characteristic features and, therefore, a careful study of this context. You cannot talk to people without knowing them well.

Could you tell us about your theological formation and the challenges you faced in an increasingly post-Christian province like Quebec?

In Quebec, I made my first theological studies. It was a kind of baccalaureate (five years of theology and three of philosophy). After two years of parish ministry, I left Quebec for Germany (University of Tübingen first and then Regensburg) to devote myself to my doctoral research under the leadership of professor Joseph Ratzinger. At the end of my Ph.D., my superiors called me to Rome to teach at the Alfonsiana Academy in the company of Bernard Haring and others, and I’ve remained in Rome since that time (1975).

So, I’ve never returned to my country as a theologian proper. Noting well the plight of Quebec from a post-Christian point of view, I almost never had the opportunity to reflect deeply and publicly about the huge challenges that this country has recently gone through and is still going through.

Who do you view today as leaders in the study/elucidation of Catholic theology?

It is difficult to answer this question taking into account the pluralism of theology today. Before Vatican II, the situation was different. There was a diversified consensus, yes, but it didn’t lessen the unity of thought between the different theological schools (they were then crystallized in the doctrine of the Council), with great theological figures, we can say, as Rahner, Ratzinger, Congar, de Lubac and many others.

Today, the situation is very different. We are no longer in the time of recollection, but the time of sowing in many different fields. This means there are still no “masters” of the stature of those of the recent past to emerge, which does not mean that they don’t exist. The future of the Church’s life will reveal them to us. For the moment, it is still too early to indicate that or the other.

Many are concerned about the Extraordinary Synod on Marriage and the Family, especially with regard to the reception of holy Communion by divorced-and-remarried Catholics. Could you explain how Catholic theology can be developed in the context of the magisterium?

The development of the doctrine, even in very complex areas, such as the one mentioned, has a necessary condition: the quality of theological reflection. Development of doctrine (if one needs any development) is not done through slogans, but very often through much suffering and full accountability, both on the side of those who believe it and on the side of those who experience it.

In the mentioned case, it seems to me that the question raised shows the need more for a theology of marriage (in its human and divine dimensions), conceived in the light of the Christ-Church relationship and ordered to show (not impose) the meaning of the serious needs of the “great mystery” that is Christian marriage. The mens (mindset) today around sexuality in general does not help to harmonize the “mystery” in question. But a real, livable and salvific solution is, in my view, the price of the respect of the “mystery.”

How much have you been influenced by the thought of Joseph Ratzinger-Pope Benedict?

Meeting with Joseph Ratzinger and his theology was great for me. I read Ratzinger for years. I wrote about some of the key points of his thought. I have moderated many scientific papers on his thinking. The penultimate one in this regard was a doctoral dissertation of 941 pages, entitled “Communion and Person: The Perspective of Joseph Ratzinger,” written by Don Claudio Bertero and awarded the best work of the academic year 2012-2013 at the Pontifical Lateran University.

In addition to meeting on the academic level, there are personal relationships that have never been lacking in the later years and which have continued to inspire me in my research.

Do you have any personal memories of studying under his direction in the 1970s? Have you ever participated in the annual Schülerkreis?

So many memories. The most important one was the strength of his sharp and illuminating intelligence that connects readily with the disarming simplicity of his person. Since then, I realized that greatness of mind and sincerity of heart can and should go together.

I participated profitably in some important meetings of the Schülerkreis.

What are your thoughts on Evangelii Gaudium (The Joy of the Gospel), from a doctrinal point of view? And what impact does an apostolic exhortation or a papal interview with a newspaper have on the magisterium?

The apostolic exhortation Evangelii Gaudium is a doctrinally rich text and not always easy to understand as a whole, given the nature of the text. To savor and collect all the richness of it, we still need a lot of time. I note that the second issue of the journal of the academy, PATH, will offer a set of theological opinions about some of the doctrinal elements of the papal document.

Secondly, there are different types of papal interventions. Not all are of equal scope, in the strict magisterial sense. For example, an interview, a sermon, an apostolic exhortation, an encyclical are, from this point of view, very different. But respect for the “ordinary” magisterium of the first Pastor of the Church is always required.

Edward Pentin is the Register’s Rome correspondent.