Abducted by Art

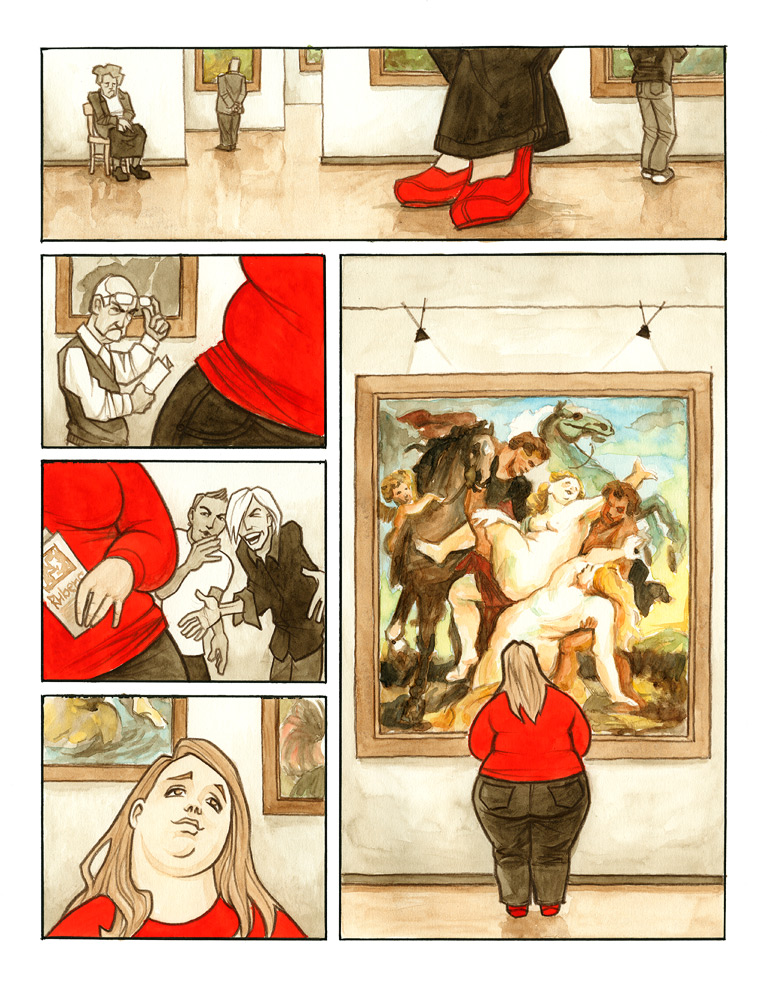

Take a look at this piece, "Wrong Century" by one Tomas Kucerovsky

Me gusta! Simple, elegant, eloquent, and finely balanced with a little unexpected punch, just like an (admittedly minor) work of art should be.

Of course, the inevitable cadre of incorrigible point missers are saying, "Yes, but don't you realize that the picture she's looking at shows the rape of the Sabine women? Are you saying that you wish you lived in a century when rape was okay?"

To them I say, "Le sigh." First of all, the title "Wrong Century" clearly refers to the century in which the museum painting was made, not the century it depicts. The girl in red is pining for a day when a beautiful and desirable woman had more than a little meat on her bones (although the comic artist has actually added quite a few pounds to the ladies in the museum painting. In Peter Paul Rubens' original, "Rape of the Daughters of Leucippus," the women were realtively zaftig, but also quite firm and muscular).

The second point, barely worth mentioning, is that although this frequently-depicted scene is generally called "The Rape of the Sabines," that's a sort of archaic mistranslation, and ought to be rendered "kidnapping" or "abduction." So, still not exactly When Harry Met Sally, but, according to the historian Livy, via Wikipedia (yes, I said "Wikipedia," because it's almost the weekend and what do you want from my life?), Romulus and his men actually grabbed first, but then made an offer of marriage to the kidnapped women, including property rights and so on, without actually raping them.

But yes, the painting in the comic above shows violence against women, and eroticizes victimhood -- quite literally, with Eros, the god of desire (the Roman name is "Cupid") peeking out archly on the left.

And so It's de rigeur to gasp in disgust over the many dozens of depictions of this scene, which has been a favorite for many centuries. What does it say about women and how we treat them and how we think about what they are for and what they enjoy? Bad things! It says bad things! Bad picture, bad!

But here is my plea to you: can we just look at the picture -- just look at it, without putting our modern selves into it?

Maybe "The Rape of the Sabines" is a scene depicted in painting and sculpture over and over again because of a centuries-long history of misogyny. But maybe it's also a nice opportunity to play with contrasts of every kind. The overall composition of the piece (you can see it better if you squint) is a giant X, and this visual theme of opposition is repeated several time: see, for instance, the arm of the Roman on the left crossing over the white leg of the woman on the top. It's a painting all about contrasts: white skin against red, dark hair and fair, violence and pliability, grim purpose and delicate anguish.

So take that notion and bring it back to the comic book art. I would venture to say that the artist deliberately chose the Rubens painting because he's also making a little comment about contrasts. Part of what makes the comic so poignant is that this well-dressed, privileged young woman is doing something which everyone else in the museum is unable to do: she's just looking at the picture. She's being plucked up into the pure visual moment of the scene, without being distracted by obvious facts, like the fact that she would probably hate living in Rubens' century or the Sabine's century -- that, fat or no fat, her life is immeasurably more pleasant than theirs.

And yet her longing is sincere, if not sensible. I mean, here she is, strolling through an air-conditioned museum in the middle of the day, and finds herself naively pulled with envy toward a scene of violence and pain. She's just looking at the painting -- imagine that?

I think this piece pokes fun not only at the nasty patrons who think she's gross, but at the girl herself, who succumbs to a moment of innocent, mindless longing. Probably this piece is a statement about changing attitudes toward feminine beauty, but I think it's at least partly playing on the idea of contrasts -- and about how small we make our world when we can't see past what we're used to seeing. The disapproving men in the museum can't see that the girl's face and hair are lovely, even though her body is several sizes larger than it's supposed to be; the girl can't see that the women in the painting are in pain; and the typical modern viewer can't see any painting at all, because we're so wrapped up in figuring out whether or not it validates our 21st century understanding of society.

But most of all, it's about longing. See how the fat girls' face echoes the face of the Sabine woman in the painting.

It's a moment of passion, a deep, emotional loss of self. You could say that the girl in the museum has been abducted by the scene before her -- swept away and made powerless (with just the hint of pleasure) by something she can't control. Yes, rape is wrong (and I'm hoping against hope that nobody reads this post as trivializing rape!). Glorifying rape is wrong.

But giving ourselves over to something powerful, something directly opposite to what we are and what we cherish? This is what great art does to us: it plucks us out of ourselves, gives us the treat of longing for something we can't really use. It kidnaps us, with our half-willing permission:

So please, let's put aside the tut-tutting when a painting shows, even glorifies, something which, in real life, every decent person abhors, whether that's rape or merely gluttony. A work of art endures through the centuries not for what it depicts, but for how it depicts it. Contrast, tension, loveliness in a struggle with violence -- and a deep, forbidden longing to be taken out of ourselves -- this is what makes a picture a work of art. Me gusta!