Rémi Brague: Ratzinger’s ‘Progressivism’ During Vatican II Was Really an Effort to Return to the Sources of the Faith

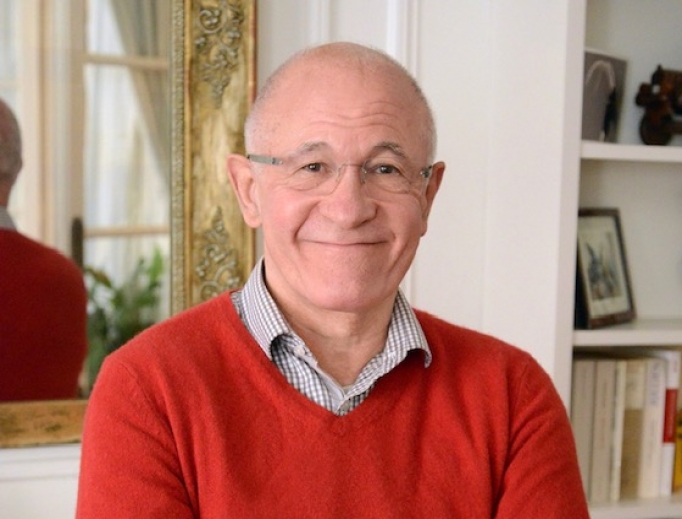

The noted French philosopher, who rubbed shoulders with the future pope in the years following Vatican II, discusses the main aspects of his legacy as well as misunderstandings surrounding his thought and work.

Although the intellectual stature of Benedict XVI is a commonly accepted fact, even by many of his most fervent opponents, the true essence of his thought remains subject to all sorts of interpretations, as subtlety does not lend itself to labels.

Classified as a conservative and nicknamed “God’s Rottweiler” during his later years as the cardinal prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, the young Father Joseph Ratzinger of the Second Vatican Council had troubled some of his peers due to his reforming audacity.

But according to French philosopher Rémi Brague, the evolution of the thought of the man who subsequently became pope under the name of Benedict XVI must be read in the light of the historical context, in order to be understood.

He engages with this task in this Register interview, delivering his personal analysis of the work of the German Pope in the wake of Benedict’s Dec. 31 death.

A professor emeritus of medieval and Arabic philosophy at the Sorbonne, Brague is the recipient of a number of awards, including the Ratzinger Prize in 2012. He first met the Pope Emeritus in the 1970s, not long after the foundation of the international theological review Communio, in which they both participated. He has been an firsthand observer of the theological and philosophical debates that have taken place in the Church in recent decades.

Do you remember your first meeting with Joseph Ratzinger? What are your most vivid memories of him?

If my memory serves me right, I saw the still young Joseph Ratzinger for the first time in 1975, in Munich, on the occasion of a meeting of the international journal Communio — which, thank goodness, is still publishing. The French-speaking edition was about to join the editions which were already extant, namely the Italian, the German, the Croatian and the American ones. The Spaniards probably were there already, although their edition wasn’t yet extant, but I may be wrong. The Germans had organized a public disputatio [discussion] of sorts in which Ratzinger set forth theses which were meant to be challenged by one member of each board. I was the French delegate, simply because I spoke German.

Ratzinger’s main thesis was then that the years which had followed the close of the Council had had quite a negative effect on the Church. The members of the panel were more sanguine. I’m afraid to have to confess that he was right and we too naive. He was a staunch supporter of the Council; on the other hand, he did not accept what was then rampant under the name of “spirit of the Council,” i.e. experiments of all ilk in liturgy and even dogmatics.

Joseph Ratzinger’s work spans decades, it is colossal and multifaceted. What are the most central aspects of his legacy for you personally? What do you think history will remember about him?

Of course, I could tell you what I would wish to go on bearing fruit, but this would tell you something about my own personal tastes, not about a possible future reception. I was struck, while perusing his Eschatology: Death and Eternal Life, by his humility in distinguishing what we know because God wanted to reveal it to us through Christ and what we can only timidly surmise.

In a Dominican convent, they had organized a display of books written by fathers of this order. A bulky treatise dealt with the fall of angels. A young novice had jokingly written in the blurb, “As if you were there!” Ratzinger never was so brash as to venture “where angels fear to tread.” His Eschatology: Death and Eternal Life is a model of humility in dealing with those difficult doctrines. My hunch, only what I feel in my bones — and my hope — is that his restraint in dealing with moot questions will be imitated and that theologians will do away with every form of intellectual arrogance.

Furthermore, he gave us, theologians and intellectuals of all stripes, the model of what he called an “hermeneutic of continuity,” in contradistinction to any attempt at a break with the past and to the dream of starting from a clean slate. On the contrary, he always endeavored to pour into the melting pot of contemporary thought whatever deserves to enter the synthesis, beginning with the classical tradition and the Bible, then the Church Fathers, and going on with modern thinkers like Newman, Antonio Rosmini, etc.

The prophetic dimension of his analyses of the decline of Europe is often emphasized by his followers and readers. What is the most original aspect of his thought in this respect?

Ratzinger is far from being the only thinker who reflected on Europe as a culture, and especially on its decline. He is rather to be understood as the Catholic counterpart of people like the Spaniard Jose Ortega y Gasset, who was an agnostic, or the Dutch Calvinist Johan Huizinga, not to mention his fellow countryman Oswald Spengler, who made popular the catchphrase “decline of the West” as a book title in 1922.

For him, what triggered the plummeting of European culture was the Europeans’ desire to part company with their biblical and Christian roots. Many analysts somehow felt that, but next to nobody had the pluck to put his finger on this sore point. Calling a spade a spade is not the main virtue of many intellectuals …

Your work is often compared to his, especially since you were awarded the Ratzinger Prize in 2012. Would you say that his thought has influenced you?

Humility is not my forte. Yet I feel I am not a match against a top-notch professional theologian like Ratzinger, since I am only some sort of philosopher cum historian of ideas. A comparison of my work with his achievements is ridiculous in itself. I was surprised when I received this prize made for theologians, together with a real one, an authority on patristics, the American Jesuit Father Brian Daley, professor at Notre Dame.

What rings truer is that I took advantage of his work; not that much as for the results of his research, but rather in his overall method of inquiry as well as his lucidity in the style of exposition. As a matter of fact, the Pope had begun his career as Father Dr. Professor Joseph Ratzinger, a product of the German academic tradition. He remained an outstanding teacher, even for people who never were blessed with his lecture courses and have to put up with his books.

You were among those who made possible the diffusion of the international theological review Communio in France. The review, launched at the beginning of the 1970s, was meant to develop a post-conciliar theology. What was Father Ratzinger’s state of mind when he took part in its foundation?

To some extent, the very name of the journal was a blueprint for what we intended to be: a loose federation of independent journals in which each felt free to use, or not to use, a pool of articles. The other theological journal was Concilium, with which we were often believed to compete. But the functioning was radically different, and this is decisive. In Concilium, each edition had to translate in its own language the articles that had been chosen by a central committee. Communio was and remains completely decentralized — to quote Balthasar, “a thin cobweb.” At the beginning, Ratzinger was on the same footing as the other editors of the German edition and never tried to wield any influence. The real theological inspiration, although he too refrained from bossing his companions, was Balthasar. As for Ratzinger’s mood when he began to work for Communio, this is anybody’s guess.

My own impression is that he had experienced twice the devastating effects of ideology. First, in his youth, in Hitler’s Germany, and, some 20 years later on a small scale, at Tübingen University. Some radical students gave an idea of what ideology let loose could lead to. In some places, theologians, too, were running amok and led the believers to nowhere. This lover of clear-cut ideas wanted a journal that could furnish the flock with reliable signposts in a troubled time.

He often insisted that at the time of Vatican II, in which he participated as an expert, he saw himself as a progressive. Indeed, he was considered by some of his peers as one of the most daring theologians of the Council. He stated in particular that in order to rediscover the true nature of the liturgy, it was necessary to “break down the wall of Latin.” How did he come to be called, a few years later, “God’s Rottweiler”?

The phrases “God’s Rottweiler” and Panzerkardinal (which media people among my fellow countrymen especially like) are simply stupid and should be forgotten, for the simple reason that they do not fit with the facts: a rather bashful man, always capable of listening to everybody.

It would be worthwhile to assess precisely how the word “progressive” sounded at this time. What was really progressive was rather an attempt at getting back to the sources beyond a dry and sclerosed Neo-Scholasticism. What launched the new outlook on the Catholic faith among the Fathers of the Council was rather a fourfold return: to the Bible in the wake of the Ecole Biblique in Jerusalem, to the Church Fathers, with scholars like Jean Daniélou and Balthasar, to the real Aquinas, with Henri de Lubac, to the liturgical tradition with Bouyer.

What Ratzinger endeavored to defend was precisely this new view of Christian life and thought. Paradoxically, one went forward by getting back to the old and half-forgotten treasures of Catholic Tradition.

- Keywords:

- benedict xvi

- ratzinger prize

- vatican ii

- solene tadie