SDG Reviews ‘Won’t You Be My Neighbor?’

New film focuses on Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood but looks beyond the show to its role in Rogers’ life and the larger world.

Morgan Neville’s documentary Won’t You Be My Neighbor? briefly debunks a silly, subversive urban legend about the seemingly preternaturally gentle host of Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood: a lurid fantasy about his imaginary military past and the many people he supposedly killed in Vietnam; the tattoos allegedly hidden by that cardigan sweater, etc.

There’s no mention of another fanciful story that I believed, and wanted to believe, when I first encountered it possibly 15 to 25 years ago. Perhaps you’ve heard this one, too: The story goes that Mr. Rogers’ car was stolen from the Pittsburgh WQED parking lot where he worked — but a day or two later, it showed up again with a note from the thieves reading, “Sorry, we didn’t know it was yours.”

The first story offers confirmation of our more cynical tendencies; the second, of our more generous impulses. The nasty discovery that reality is so often more complicated, darker and less reassuring than surface appearances suggest is repeated so often that we may be tempted, some of us, to suspect that goodness, sincerity and gentleness can never be trusted.

Yet we also want to believe, some of us, that even car thieves are human beings who were children once, and that however far in life they may have strayed from the lessons of respect and honesty Mr. Rogers tried to teach them long ago, somewhere deep down they still know those lessons are true. Perhaps, even if they can live with that contradiction in their day-to-day crimes, the cognitive dissonance of stealing from Mr. Rogers might be a bridge too far for them.

The first story is ludicrously false. The second probably isn’t true — but it could be true, in principle.

“Love is at the root of everything,” says Fred McFeely Rogers in an archival clip in Won’t You Be My Neighbor? “All learning, all relationships.”

Then, just as you’re thinking (if you’re like me) about all kinds of relationships that are rooted in anything but love, and wondering how anyone can say anything so saccharine-sounding, he adds a clarifying zinger: “Love or the lack of it.”

There, in a way, is the substance of Rogers’ entire career and especially of his iconic television show, which debuted a half-century ago in 1968. For decades, he simply tried to supply the love that might be lacking in a child’s world — at home, at school, in their neighborhoods, and especially in the rest of their television viewing.

That’s a lot of lack. As gentle as Rogers and his show were, Neville (20 Feet from Stardom) reminds us that they weren’t too Pollyanna to tackle tough subjects like divorce, anger, death, assassination and war, all in ways children could understand.

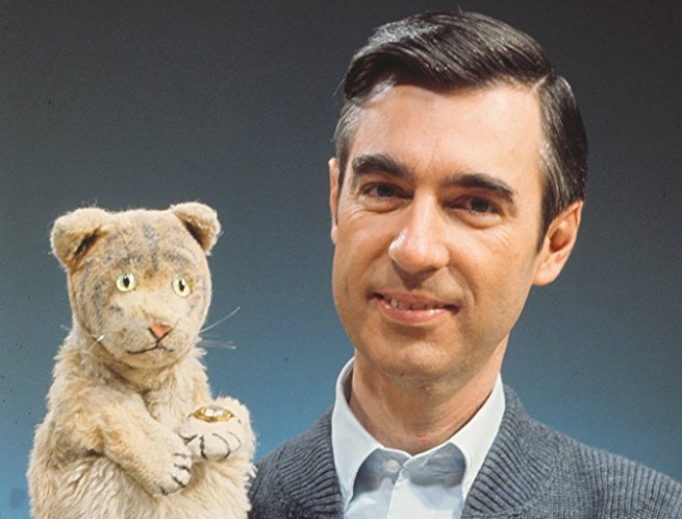

Utilizing a straightforward blend of archival footage, interviews with Rogers’ family and colleagues, and metaphorical animated segments depicting Rogers as his puppet alter ego, Daniel Stripéd Tiger, the film focuses on Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood but looks beyond the show to its role in Rogers’ life and the larger world.

Neville touches on Rogers’ early Presbyterian seminary training and studies in child psychology as well as his discovery of television and the early television work in which he created puppets and characters and wrote music that would later go into Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood.

The film also explores the cultural context and impact of Rogers’ work, from his responses to Vietnam and the assassination of Robert Kennedy to backlash from critics decrying his focus on children’s feelings and his affirmation of their specialness and parodies like Eddie Murphy’s Mister Robinson’s Neighborhood sketches on Saturday Night Live.

Disturbing footage of a segregationist dumping bleach into a recently desegregated swimming pool with black and white children swimming together provides context for a segment from the show in which Mr. Rogers and the singing policeman Officer Clemmons — played by African-American performer François Clemmons — sit together in front of a wading pool soaking their bare feet together singing There Are Many Ways to Say I Love You.

The segment ends with Rogers pointedly drying Officer Clemmons’ feet with a towel in overt imitation of Christ washing and drying the disciples’ feet in John’s Last Supper account, a symbol of service that Christ exhorted his followers to do for one another.

Clemmons talks about his misgivings as an African-American about playing a police officer, but admits Rogers’ vision won him over. He also talks about Rogers’ concerns about Clemmons’ homosexuality and the danger to the show’s funding if Clemmons were outed (and debunks any notion that Rogers himself was gay).

His last memory of Rogers, from their last show together, is a warm one: He recalls Rogers looking at him while uttering his signature line about making “every day a special day by just your being you.” Asked if he were talking to Clemmons, Rogers replied, “Yes, I have been talking to you for years. But you heard me today.”

Rogers’ Christian faith, Won’t You Be My Neighbor? acknowledges, was implicit in his whole approach; his show wasn’t preachy, but he was always preaching.

Rogers’ show was countercultural in style as well as substance. Appalled by the abrasive tone and hyper pacing of much television fare, Rogers went as slow, quiet and reassuring as possible, which is simply who he was, but also what he believed children needed.

He believed that the images we take in become who we are, and he offered children the good stuff. He never worried about holding their attention, and he never had to. Every child watching felt that he was speaking to him or her, because he was. To use a term much derided nowadays, Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood offered a safe space for children in a world they were quickly learning could be scary and cruel.

Rogers believed that television had the power to unite a nation into a single neighborhood, and in that quest he was a steady but lonely voice in the wilderness. As popular as he was and as profound an effect as he had in many lives, he couldn’t outweigh the combined influence of most pop culture that wasn’t him.

For a few formative years of our lives, Mr. Rogers showed us the way. Why don’t we walk that way? Because of all the voices dominating the discussion ever since.

Yet, like those (probably) mythical car thieves, we know deep down that he was right. An unlikely TV star in his day, Mr. Rogers he has become an even unlikelier Internet icon of goodness and gentleness. Every time disaster or terrorism strike, people share memes of his famous quote about looking for the helpers. Paradoxically, the harsher and more polemical our public discourse has become, the more this beacon of generosity and empathy has been celebrated by nearly everyone.

Ultimately, this is not because of the style or substance of Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood, but something unquantifiable and unreproducible: Rogers’ manifest goodness. His hopes for a more united country may have been dashed, but in one respect he undoubtedly succeeded: He wanted to make goodness attractive, and he did.

Is Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood hagiographical? Is it necessarily a bad thing if it is? Hagiography is usually a bad thing in biography because most of us aren’t saints. (One remarkably hagiographic detail: Each morning, after swimming laps — there’s underwater footage of Rogers’ slight frame in the pool — he stepped on the scale, and, according to the man himself, every day he weighed in at 143 pounds: a number that, to him, signified the 1-4-3 letters of the words “I love you.”)

Rogers wasn’t a perfect man, even if one of his sons recalls that it could be difficult “having a second Christ for a father.” But when his widow, Joanne, recalls reassuring him toward the end of his life, as he contemplated the Parable of the Sheep and the Goats in Matthew 25 and wondered out loud if he were one of the sheep, that if anyone qualified as a sheep, he did, it’s hard to imagine any reasonable person disagreeing.

We can’t live in Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood, and our world will never greatly resemble it. But what’s stopping us, any of us, from trying to bring to our interactions with others a little more of what we admire in Mr. Rogers? Is the divisiveness and cruelty of our world a reason not to treat each other with kindness and love, or is it more important to do so?

Like Jesus, like Mr. Rogers, Won’t You Be My Neighbor? challenges each of us to try to be better neighbors.

Would you be mine?

Deacon Steven D. Greydanus is the Register’s film critic and creator of Decent Films.

He is a permanent deacon in the Archdiocese of Newark, New Jersey.

Caveat Spectator: Some mature thematic content, including topics like racism, war and homosexuality; a gag photo of a man “mooning” the camera. Teens and up.

- Keywords:

- goodness

- movies

- mr. rogers

- sdg reviews

- steven d. greydanus