The Ecumenism of Vatican II, 60 Years Later

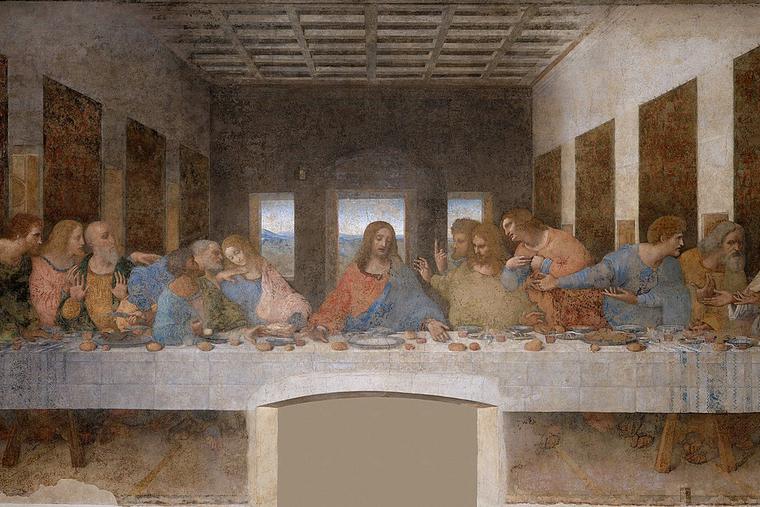

COMMENTARY: Christ’s prayer for unity, at the Last Supper, reminds us that unity among Christian believers is an essential part of the Church’s mission.

This October marks 60 years since the opening of the Second Vatican Council. The anniversary offers us an opportunity to look back on this key moment in the Church’s ecumenical journey.

The pope who initiated the Council, St. John XXIII, was deeply aware of the dynamics of world history and of Church history. He grasped the vital importance which councils have in the life of the mystical body of Christ, as a way of fostering unity and responding to specific pastoral challenges.

In the case of Vatican II, there wasn’t a clear-cut doctrinal error being addressed by the gathering, as in the case of past councils. Rather, there was a more general sense that the Church was in need of renewal so as to respond to the immense changes which the world was facing in the middle of the 20th century: the rapid advance of science and technology, transformations in forms of government and culture, along with the increased questioning of religious truth and practice.

In the face of this complex reality, John XXIII decided to convoke an ecumenical council (it was not called ecumenical for having addressed ecumenism, but because the council is binding for the whole Church). The Pope took this dramatic step in order to renew the Church in her work of presenting revealed truth in a way better suited to the modern world.

Ecumenism, or the effort to foster a greater visible unity among separated Christians, was an essential part of this message. Christ’s prayer for unity, at the Last Supper, reminds us that unity among Christian believers is an essential part of the Church’s mission. This unity became particularly relevant in the decades leading to the Council and continues be so today. As we know all too well, the first half of the 20th century witnessed a succession of totalitarian ideologies which led to bloodshed unparalleled in human history. The end of the Second World War would lead to the Cold War and the real threat of nuclear war.

John XXIII felt deeply that, precisely within this atmosphere of conflict, the Church needed to be a sign of the genuine unity and peace brought about by Christ’s Redemption. As theologians realized in the years previous to the Council, the Church can be considered a sacrament, since she visibly manifests Christ while at the same time she is a means by which grace becomes present.

In light of the stark reality of human pride and the other manifestations of human sinfulness, perhaps it’s not surprising that the Church has had to face discord over the course of her history. Such lack of harmony made itself particularly present in the great divisions which have occurred approximately every five hundred years: in the separation of the Ancient Eastern Churches from communion with Rome in the fifth century, the schism between the Eastern Church and Western Church in the 11th century, and that Protestant Reformation in the 16th century.

These separations were not simply based on doctrinal differences. These disagreements certainly existed, but — arguably — they were not the weightiest factor. A broad set of political, cultural, and linguistic differences were also at the root of divisions in the Church. And, additionally, there was an array of very human reactions, such as mistrust, fear, and anger.

The fact of division has indeed been a cause for sorrow and shame on the part of the members of the Church. Still, the Church has never been content with disunity. The means of bringing about this unity have certainly been quite different throughout the centuries. Catholics, Orthodox and Protestants have often tried to use various arguments to convince another party that they were in the wrong. Oftentimes, these disputes were based on the idea that those who were outside of the true Church were simply outside of the Church, period.

We think of words such as heretic or apostate. There was not always the need to re-baptize someone from another community who entered into a given Christian fellowship. Nonetheless, there was the conviction that a person in that separated Christian community was someone estranged from Christ as long as that individual was separated from the true Church. And so, with good intentions, and with a sincere faith in their convictions, Christians could end up treating their fellow Christians as pagans rather than as brethren.

It is within this context, along with the larger tensions present in the world as a whole, that we can appreciate St. John XXIII’s desire for a change of perspective. At the solemn opening of the Council on Oct. 11, 1962, in the presence of 2,500 Council Fathers and with the world watching in attention, the Holy Father made a proposal for the Church which built on Tradition and at the same time marked a decisively new attitude. He called on the Church to not simply be content with condemning the errors present in the modern world, but to show herself as a loving mother towards all, including her separated children.

The Council would seek to carry out this goal in many significant ways. Vatican II’s Constitution on the Church, Lumen Gentium, offers a rich vision of the Church rooted in the mystery of the Holy Trinity, and at the same oriented outward to the renewal of the world in Christ.

This is a vision of the Church which looks beyond the disputes of the preceding centuries. It is a conception which, without ignoring the institutional and visible aspects of the Church, seeks to express the mystery of the Church in terms of God’s desire to raise man to a sharing in the divine life.

In this perspective, we can better appreciate the supernatural unity present among all those who profess the name of Jesus Christ, even in the midst of the various divisions. The Council famously described this unity with the assertion that the Church of Christ subsists in the Catholic Church (Lumen Gentium 8). This phrase allowed for the Catholic Church to profess faith in her special identity while at the same time recognize the “many elements of sanctification and of truth” found outside of her visible structure.

Here one can see a genuine change of perspective, within the one mystery of faith. The point of departure is not confrontation or argument, but unity. Authentic ecumenism starts with such an awareness: It is not simply about seeking unity, but about recognizing and bringing to fulfillment the unity which already exists, as a gift from Christ to his Church.

This is the attitude which permeates the Council’s vision of the Church and in particular the Council’s Decree on Ecumenism, Unitatis Redintegratio. The decree’s title reminds us of a unity which needs to be restored or renewed (redintegratio), but which does not need to be brought into being for the first time.

Vatican II has also offered a clearer vision of exactly what visible unity would involve. The restoration of visible unity would never simply be about non-Catholic Churches becoming like the Catholic Church. This is not because the Catholic Church would betray her identity, but because her very identity is dynamic. The Church is “at the same time holy and always in need of being purified,” and she thus ever follows “the way of penance and renewal” (Lumen Gentium 8).

This renewal of the Church would not lead to her be less “Catholic,” but rather more fully catholic, meaning more “universal.” Vatican II was a decisive moment in the fuller realization of this catholicity. In response to the needs of the Church in a new and more globalized world, the Council wanted to clearly state that catholicity or universality is an essential characteristic of the Church (see Lumen Gentium 13).

A deeper awareness of the Church’s catholicity offers a key remedy to the national and cultural differences that have so often been at the root of division. The Church’s catholicity reminds us that the many distinct perspectives and ways of expression, present among the various cultures of the world, need not be an obstacle to unity, but rather are precisely the richest expression of genuine unity. The Church’s unity, after all, is never the unity of a purely human institution or a nation, but the unity brought about in the communion of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.

Pope Francis has expressed the ecumenical experience in the phrase “journeying together.” These words encapsulate a key truth of the Church’s path over the last six decades, in the midst of the many challenges from the inside and the outside which the Church has faced.

The various Christian communities have come to recognize, with ever greater clarity, that they are called to advance together, as brothers and sisters, towards the destination of full unity. The ecumenism inspired by Vatican II offers a powerful sign of Christ’s presence, here and now, in the midst of the shadows left by human weakness and sin, ever accompanied by the light of the Holy Spirit.

Father Joseph Thomas is a priest of the prelature of Opus Dei. He serves as chaplain of Mercer House in Princeton, New Jersey. He has served as editor for Church and Communion: An Introduction to Ecumenical Theology (CUA Press), written by his dissertation director Philip Goyret.

- Keywords:

- vatican ii

- ecumenism

- eucharist

- the last supper