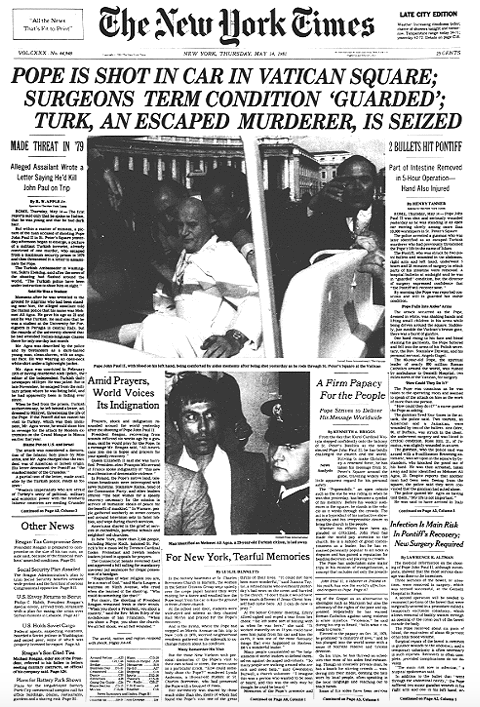

St. Peter's Square, May 13, 1981

Remembering the assassination attempt on Pope St. John Paul II 35 years on.

On a calm and sunny May afternoon 35 years ago this Friday, on the Feast of Our Lady of Fatima, Pope St. John Paul II was driven into St. Peter’s Square to deliver his weekly catechesis.

He was going to talk about the role of work and workers to mark the 90th anniversary of Pope Leo XIII’s encyclical Rerum Novarum, and announce the creation of what would become the Pontifical John Paul II Institute for Studies on Marriage and Family (the full text of what he was going to say on that fateful day was published by Aleteia for the first time in English last week).

But at 5.19 p.m., Turkish gunman Ali Agca emerged from the adoring and excited crowd of pilgrims and opened fire on John Paul, shooting him four times. Agca threw his Browning 9mm pistol under a truck and tried to flee the scene but was swiftly grabbed by Vatican security chief Camillo Cibin, a nun and several pilgrims who prevented him from getting away.

"He arrived so calm that for a moment I believed he was dead,” recalled Professor Alfredo Wiel Marin, one of the surgeons who operated the Pope. “Then he passed out.”

He said the Pope had three wounds and that the ones in the abdomen were “very serious, that could have proved fatal.” He said it was “incredible” that a bullet had been stopped from going further. “One centimeter more and it would have been the end.”

Professor Marin’s testimony is one of a series of fascinating recollections of the attack, featured over the past week in a series of articles by Luis Badilla, editor of the Vatican’s semi-official aggregate news site Il Sismografo.

Badilla, who was working for Vatican Radio at the time, recalled first learning of the assassination attempt when he overheard the “unmistakeable voice of a Brazilian colleague saying with a somewhat shaken voice: ‘There’s been a shooting in St. Peter’s Square.’”

“It was about 5.20 p.m.,” he said. “Moments later the entire Radio was submerged by an avalanche of telephone calls. All were asking in various languages: ‘But it is true that they shot the Pope ? Is it true that the Pope has been killed?

“So it was that we, mere operators of the Pope's radio station, knew it wasn’t just any shooting, but that the Holy Father really had been shot. That must have been more or less around 5.30 p.m.”

Much confusion and mayhem filled the square. “From the the radio I walked quickly toward St. Peter's Square on the Via della Conciliazione,” Badilla remembered. “I understood immediately that the situation was serious, on the verge of some kind of collective anxiety. I saw people running, disoriented and many in tears. Mothers dragging their children as if fleeing a bomb explosion.” People thought two different things had happened: that "they killed the Pope" or they had assassinated Marco Pannella, an Italian politician and leader of the Radical Party. Someone told Badilla that he thought there had been a shooting between street vendors. “There was great confusion and the noise of sirens of many police cars arriving was deafening.”

Badilla managed to get as far as the obelisk in the center of the square, but police forbade people from going further. A priest from Parma told him that “one or two people” had shot the Pope. “’It seems to me that they have taken him away alive but badly injured. It’s horrendous!’, he said. ‘We just have to pray that Our Lady protects him,’ he added, his eyes filling with tears.”

Badilla then travelled to the Gemelli Hospital where he bumped into Cardinal Agostino Casaroli, the Vatican Secretary of State. “We embraced without exchanging a single word,” he remembered. “His hands were very cold and his face, usually smiling, was tense and still.” Cardinal Casaroli told him to “pray a lot, a lot.”

Another story recounted in the Il Sismografo series is that of Sara Bartoli. Now 37 and then aged just a year and a half, it’s possibly partly thanks to her that John Paul II’s life was saved. Agca told investigators that it was because the Pope had picked Bartoli up to kiss her that he lost his aim. He opened fire just after the Pope handed Bartoli back to her mother.

Various theories have been put forward on who was behind the assassination, including that Agca was backed by the KGB, but even today there is still no definitive and documented version of what really happened that day.

Although just a child at the time and then not a Catholic, I vividly remember hearing the news. What struck me most was John Paul II’s almost instantaneous reaction to forgive the man who tried to assassinate him. It seemed then and still seems now so remarkable and yet so fitting one could only really attribute it to supernatural grace.

Pope John Paul always credited Our Lady of Fatima for saving his life, and visited Fatima a year later. In his homily there, he said:

“And so I come here today because on this very day last year, in Saint Peter's Square in Rome, the attempt on the Pope's life was made, in mysterious coincidence with the anniversary of the first apparition at Fátima, which occurred on 13 May 1917.

I seemed to recognize in the coincidence of the dates a special call to come to this place. And so, today I am here. I have come in order to thank Divine Providence in this place which the Mother of God seems to have chosen in a particular way. Misericordiae Domini, quia non sumus consumpti (Through God's mercy we were spared-Lam 3:22), I repeat once more with the prophet.”