Rembrandt’s Holy Family and the Presentation in the Temple

Rembrandt painted the Presentation many times in his life. Two of them — one from early in his career, one late — deserve our attention.

The Church celebrates the Feast of the Holy Family on the Sunday between Christmas and New Year (provided they are both not Sundays themselves, in which case Holy Family defaults to Dec. 30).

Last week, we noted how the Church deals with the focus on the Annunciation when only one Gospel (Luke) actually reports the event but the Sunday Lectionary cycle rotates over three years to cover each of the Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke) as far as possible. In the case of the Annunciation, the Church creates a kind of “Gospel triptych” — the Annunciation as revealed to Mary and as disclosed in its consequences to Joseph and Elizabeth.

The Church faces a similar dilemma on the Feast of the Holy Family. Because the Gospels are theological statements and not biographies, they do not give us every detail of Jesus’ life but, rather, only those with a relevance for our salvation.

All four Gospels primarily recount the three years of Jesus’ active ministry, leading up to his Passion, death and Resurrection. Neither Mark nor John even speak of Jesus’ human birth; only Matthew and Luke have “Infancy Narratives.” Even those Infancy Narratives focus primarily on events and the period surrounding Jesus’ conception and birth. Except for those moments and Jesus’ Finding in the Temple at age 12, the whole period before age 30 is Jesus’ “Hidden Life.”

That makes it hard to pick out Gospels to illustrate the life of the Holy Family. This year, we read of Jesus’ Presentation. In Year A, we focus on the Flight into Egypt and the return to Galilee. In Year C, we read of Jesus’ Finding in the Temple. There isn’t much else to read from the “Hidden Life.”

This Sunday, we read the Gospel of the Presentation. It’s in fact that term’s a bit inaccurate, because there are two events occurring here: the Presentation of Jesus in the Temple and the Purification of Mary. According to the Old Testament (Numbers 18:15-16), a firstborn male son had to be presented and redeemed in the Temple. Likewise, all women had to be “purified” after giving birth (Leviticus 12:1-8) because blood was regarded as the seat of life and so blood spilt in or after childbirth made a woman ritually unclean to participate in sacred worship. These two events are, in fact, conflated in today’s Gospel as well as in what we Catholics now call the Feast of the Presentation of the Lord on Feb. 2, 40 days after Christmas.

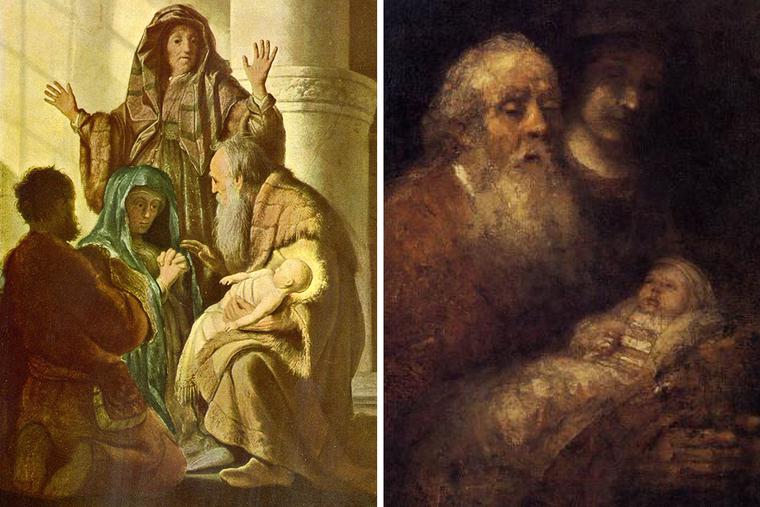

Rembrandt van Rijn painted the “Presentation” many times in his life. Two of them, one from early in his career (ca 1627), one late (1669) deserve our attention.

The Dutch artist tends to capture those figures the Gospel gives most attention to: Jesus, Mary, Joseph, Simeon and Anna. In his 1627 painting, they’re all there. In his 1669 painting, the figures are pared down to Jesus and Simeon, Mary in the shadows.

Who to put in representations of the Presentation is a challenge, for two reasons. First, from a Jewish perspective, Simeon and Anna are pretty marginal figures. Simeon is not the Temple representative who presents Jesus or purifies Mary. In some sense, Simeon and Anna are merely devout old Jews frequently in the Temple, not unlike the occasional old man or woman still encountered “night and day” (Luke 2:37) as quasi-fixtures in the back of some churches.

Second, even when artists try to depict the actual Temple ritual, they sometimes situate Mary in the midst of a larger entourage (e.g., Hans Holbein who, in his case, also has everybody decked out anachronistically in Gothic/Renaissance garb). It’s sometimes hard to say whether the painter thinks that crowd accompanied the Holy Family or just happened to be hanging out in the Temple and piously came over. Neither seems particularly accurate.

As Luke (2:24) points out, Mary offers two turtle doves for her purification. The Bible proved that as a sliding-scale, reduced offering for the poor (Leviticus 12:8) who could not afford a lamb. In that light, one doubts the Holy Family rubbed elbows with that rank of folk or might have caught their attention, any more than Simeon or Anna likely did. Of course, there were artistic conventions of painting contemporaries into pictures or showing the nobility and class of the Holy Family. Once upon a time, even the poor made a point of having their “Sunday best” for church. Truth be told, however, it’s far more likely that the Holy Family slipped in to the Temple, piously performed their religious duties, and slipped out unnoticed except, perhaps for the two old people that, led by God (Luke 2:26-27, 38), crossed their tracks. (At least that’s how the Polish Jewish Christian writer, Roman Brandstaetter, imagined the Presentation).

That’s why I prefer focusing on Rembrandt’s sparer depictions of the Presentation. As I said, the 1627 painting shows only the five individuals listed by proper names in Luke 2:22-38. None of them appears particularly affluent. Joseph’s cloak seems a bit rough and, as usual, he is self-effacing (to the point we do not see his face). Simeon holds Jesus, just as Luke (v. 28) says. It’s not wholly unexpected gesture: once upon a time, an older man or woman that might admire your child and want to hold him was not considered a threat. Mary’s eyes are wide open and her face serious as what Simeon says: what mother wouldn’t be if told her Child would be a “sign of contradiction to be opposed” that will also tear her own heart open with a sword (vv. 34-35)? Anna, in keeping with Luke’s implicit chronology, looks as if she has stumbled upon this gathering and realizes why God has put it along her path.

The three adults gathered in close and in kneeling/sitting positions seem almost Trinitarian; Anna, hovering over, almost expresses unity, her hands in surprise and perhaps in blessing. Visually, she binds them together and appears like a protective circle, from her hands to Joseph’s head.

As I noted above, the venue seems to be some corner of the Temple, hardly where the Temple Establishment is gathered. The light (light is always a central element for Rembrandt) entering the scene not only enables us to see this quintet clearly, but could be said to be the Divine enlightenment by which Simeon realizes the Holy Spirit has been faithful — that he would not see death until his eyes have seen “a light for revelation to the Gentiles and the glory of your people, Israel” (v. 32) — and by which Anna, “coming up to them at that very moment” is inspired in thanksgiving to speak about the Child …” (v. 38).

The 1669 Rembrandt pares the scene down even further, to three people. Rembrandt, with his unique use of light, primarily illumines only the two figures he is most interested in: Jesus and Simeon. Simeon — like Rembrandt — has aged. He seems to have traded cloaks with Joseph. (Remember that Rembrandt ended his days in poverty.) The focus of Simeon’s eyes suggests he is at least significantly visually impaired, if not physically blind. That does not matter, because the Holy Spirit enables him to have “seen your salvation, which you have prepared in the sight of all nations” (vv. 30-31) — but which the rest of the Temple Establishment happened that day not to notice. Mary (at least in my opinion — one commentator thinks she is perhaps Anna) is partially illumined next to Simeon.

One has the impression that perhaps 1627 Rembrandt’s Simeon is already speaking his prophecies about Jesus and Mary (vv. 34-35), while 1669 Rembrandt is still on the Canticle of Simeon (vv. 29-32). This painting dates from the year Rembrandt died: is his reduced population even more indicative of getting ready for the personal encounter with Jesus, the highpoint of Simeon’s, his, and everyone’s life?

For Rembrandt, light hides and illumines, much as the Gospels also conceal the unessential and reveal the salvifically relevant. Like this period of Jesus’ life, Rembrandt hides a lot but casts a light on the key figures involved in this “little epiphany,” when God further reveals Jesus’ identity and mission to at least four people: Mary, Joseph, Simeon and Anna. Or, perhaps five, if we can include the artist.

- Keywords:

- Holy Family

- Rembrandt

- presentation