Fighting the Zeitgeist in Old Catholic Japan

On a Lenten Friday in 1614, the Tokugawa scourge arrived in Chikuzen, Japan.

Three days they hung by their feet from the tallest pine tree in Hakata, encouraging one another to fight on. Joachim’s head dangled just above the heels of Tomeh, who hung below him, and both kept thanking God for the mercy of letting them imitate Saint Peter in their suffering — that servant of Christ who had been crucified upside-down. Not quite the example that Kuroda Nagamasa, lord of Chikuzen, had aimed at when he ordered this torture for the only two holdouts in his campaign to clear his capital of openly-professing Christians. The Tokugawa scourge had arrived in Chikuzen, choosing its first victims on a Lenten Friday of 1614.

In 1612, Tokugawa Ieyasu, the Daifu (“retired” Shogun but de facto ruler of Japan), had banished all Catholics from his service and forbidden samurai and common soldiers in Tokugawa lands to profess the Faith. The ripple effect across the country was immediate, since every daimyo’s life and fortune hung on the fragile thread of the ruler’s displeasure.

Still, his ban was not mandated in domains not under direct Tokugawa control, and Chikuzen, way down in Kyushu, was Kuroda territory. Besides, Nagamasa’s army had fought so well on the Tokugawa side in the great battle of Sekigahara, which secured Ieyasu’s takeover of Japan, that Ieyasu honored him as the greatest contributor to his victory. Thus did Nagamasa think himself insulated from what seemed like a faraway storm with little chance of wreaking its damage on Chikuzen or the rest of Kyushu.

After being harried, though, by Hasegawa Sahioye, Ieyasu’s henchman in Nagasaki, Nagamasa thought it prudent to tread lightly on this shaky ground of change. He asked a priest to give him a list of all the Catholic samurai in Chikuzen. The priest politely refused, explaining that doing so would be both a sin and destructive of his very purpose in coming to Japan. He added that he and his fellow clergy would die rather than obey a command so contrary to God’s law. Nagamasa therefore restricted his hounding of Catholic samurai to those he already knew of.

Things would change in 1613. On his obligatory New Year’s visit to the shogunal court, Nagamasa keenly felt the ruler’s displeasure at his failure to have scoured his domain of every last Christian warrior. He thus wrote to the Jesuit Provincial, requesting that all priests in Chikuzen be withdrawn to Nagasaki and that their churches be pulled down — adding, though, that he would look the other way if they visited their flocks in secret.

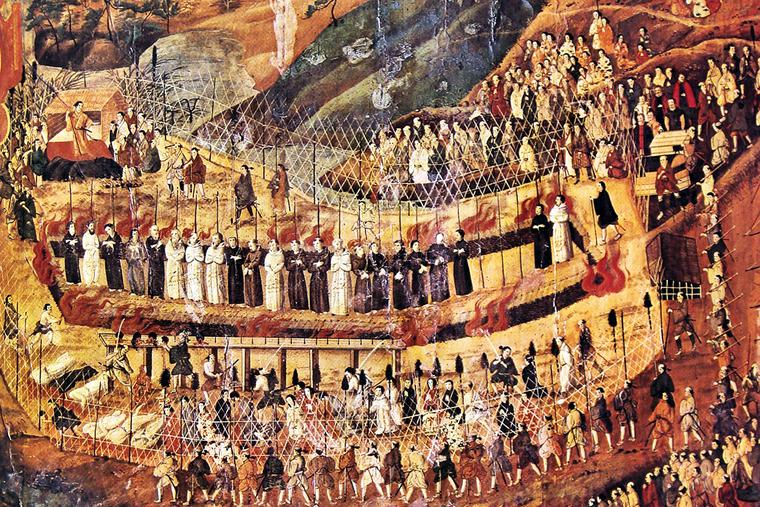

Yet Nagamasa would soon be compelled to make a bolder show of fealty to the Daifu: in 1614, Ieyasu stamped an ironclad, nationwide ban on serving Christ on pain of death. Nagamasa duly ordered all heads of families in Fukuoka, his capital, to gather in the courtyard of a certain temple to be examined for their religious convictions. Two Catholic stalwarts were quickly singled out for mise-shime, i.e., to be made examples of, and the rest sent home. These two would serve to show all of Chikuzen what stubbornly-faithful Catholics could expect from Kuroda Nagamasa’s newfound anti-Christian zeal.

Behold the criminals:

Joachim Shinden, about 50 years old, was a physician who gave free treatment to the poor and worked as a catechist for the Fathers; he also headed the Confraternity of St. Ignatius. Tomeh Watanabe, a robust young man, was “fervent in encouraging the Christians, with exhortations and examples of mortification and penance, to persevere in the Faith.” He fasted on Saturdays in honor of the Blessed Virgin and on Friday nights walked the beach to scourge himself and pray to his God in solitude.

Such staunch fidelity to Christ clearly would not do in the new Japan of the Tokugawas. Nagamasa’s men made “great efforts “ to convince the two faithful Catholics that they should “adapt themselves to the times.” A phrase that appears time and again in the histories of Father Pedro Morejón, who well knew the country and “the times.” Tomeh and Joachim would have none of it: they told Nagamasa’s men that betraying their Creator was unthinkable.

They were arrested, tightly bound, and finally hung from that tall pine tree overlooking Hakata and its broad bay. The next day a great throng of people came to see the spectacle, among them both Christians and pagans. Some of the latter asked Joachim why he was so stubborn in holding out for “something as uncertain as salvation.”

Joachim asked them to imagine themselves being given the choice to either risk their lives in service to Nagamasa or betray him and thus be taken for enemies and traitors to their feudal lord. Would they not suffer any travail, even death, rather than shirk their duty? How then could they expect faithful Christians, cognizant that they are God’s creatures and constant partakers of his mercies, to betray him, no matter how much suffering they must endure?

This answer opened many eyes.

When a Christian approached the tree to ask Joachim how he was faring, he said he had never known such pain as this, even in battle — it felt as if he were being sawn in half from top to bottom. He added, though, that he was consoled in knowing that he could apply his pain to Christ’s sufferings in partial atonement for his sins.

Tomeh, meanwhile, had his scourge with him and used it freely on his own back while hanging upside-down from that tree.

Having hung the two Catholic stalwarts on that tall pine tree three days and two nights without allowing them even a sip of water, Kuroda Nagamasa found them still unmoved. He needed something more persuasive. His men brought them down from the tree and tied them to an instrument of torture — a sort of cross like a wooden ladder with a crossbeam. This only made Joachim and Tomeh glory in the knowledge that their persecutors had rendered them all the more akin to Christ in his Passion. They were ecstatic in their agony.

News of this constancy was all that Kuroda Nagamasa could bear — he ordered that those stubbornly-faithful Catholics be taken down from their cross and beheaded. Joachim, no longer able to move, had to be carried to the execution-ground on the shoulders of some soldiers as Tomeh marched on his own, both of them glad to be giving their lives for Christ.

Arrived at the spot whose soil would drink their sacred blood, the two victors knelt in prayer before bowing their heads to bare their necks to the executioner’s sword.

Joachim and Tomeh’s severed heads would be put on display there on the spot where they had died — stark monuments to their earthly lord’s apostasy. Kuroda Nagamasa had once been a Catholic himself, you see, baptized and christened “Damian” — but unlike those two Christian stalwarts, the daimyo of Chikuzen had adapted himself to the times.

Luke O’Hara became a Catholic in Japan. His articles and books about Japan’s martyrs can be found at his website, kirishtan.com.

- Keywords:

- Japanese martyrs