A Tale of Two Easters and a Miracle in Japan

In 1616, on Holy Saturday evening, a great fire — not lit by human hands — appeared on a mountaintop in Japan

In the years before the great Tokugawa persecution of the Catholic faith, a beautiful cross of cedar stood on a mountaintop in the town of Akizuki in the domain of the Kuroda clan in northern Kyushu. It had been planted there by the lord of Akizuki, a Christian samurai named Kuroda Sōemon Naoyuki, christened Miguel at his baptism in the town of Nakatsu (in modern Ōita Prefecture).

Naoyuki became Miguel on Easter Sunday of 1587. He took that name in good faith, a commitment he embraced with all his heart and clung to unto death as befits a valiant warrior. Naoyuki had fought as a vassal of Toyotomi Hideyoshi in his teens, in the days before that warlord adopted the surname “Toyotomi” to counterfeit noble birth and thereby smooth his takeover of Japan. Yet it was that same Hideyoshi who in that very year of 1587 banned the Faith, trumpeting his dark proscription on July 25, the Feast of Saint James.

Miguel had pledged his sword to Hideyoshi, but not his soul. He went on living and professing his faith despite the falling-away of some notable Catholics, and in 1600, when the head of the Kuroda clan gave him charge of Akizuki, he devoted himself to the protection and nurturing of its Christian community. When the Jesuits were hounded out of the Kurodas’ port-town of Hakata at the instigation of Buddhist clerics in 1602, Miguel not only gave them safe haven in Akizuki but also succeeded in effecting their safe return to their forlorn Hakata flock. In 1607 alone there were 2,000 adults baptized in Akizuki and a new church built at Miguel’s expense. Father Pedro Morejón, who was in Japan throughout this period recording the Jesuit mission’s triumphs and vicissitudes in detail, writes that more than 5,000 souls were baptized in Miguel Kuroda’s Akizuki in a mere two years. Father Morejón called Miguel Kuroda “a diehard defender of the fathers and the Christians.”

And defending they did need. Although the tyrant Hideyoshi had died in 1598, his proscription of the Faith lived on, and the ruler who succeeded him, Tokugawa Ieyasu, would soon prove an even more vicious enemy of the Church in Japan — indeed, its determined executioner.

Miguel Kuroda fell mortally ill in 1609. As he lay on his deathbed, he gave his final orders to his son Naoki, christened Paulo, who would be taking the reins of Akizuki. This was Miguel’s only instruction to his heir, the new guardian of Akizuki’s Christian flock: “Keep the faith.”

To the physician at his bedside, a pagan friend he had long been trying to convert, Miguel Kuroda made a final plea that the man come to his senses, get himself baptized, and possess eternal life. “I declare to you once more that there is no other truth than that taught by my master Jesus Christ: any other religion than his is vanity and folly,” he insisted. Since he was on his deathbed, Miguel went on to assure his friend, he could tell no lie, lest that lie send him to hell.

Whether or not Miguel’s friend followed his advice we cannot say, but the fate of Paulo, his heir, is recorded in history. He died in 1611 in unclear circumstances, perhaps assassinated, and the rule of Akizuki devolved to the Kuroda clan’s capital of Fukuoka. There, sympathy for the Kirish’tan sect — i.e., the Catholics — was in ever shorter supply, for the political winds blowing down to Kyushu from the throne rooms (so to speak) of the second Tokugawa Shogun and his father, Ieyasu, were waxing too cold to bear.

Thus, the legacy of Miguel Kuroda Sōemon Naoyuki was in grave peril. But what of the beautiful cross of cedar that he left behind on that mountaintop?

Within three years of Miguel Kuroda’s death, the church-demolishing and cross-burning frenzy of the Tokugawa persecution had begun. Akizuki was a peaceful town, a picture-perfect haven nestled in the mountains of rural Chikuzen Province, a town where Catholic and non-believer might have gone on living side by side in harmony: witness Miguel’s deathbed entreaty to his pagan friend. Yet the Tokugawa terror did indeed reach Akizuki and there dug in its talons. All Catholics were to apostatize at once; any holdouts would be listed as rebels under sentence of death. Many did in fact hold out, affixing their names to a roster of Christians willing to die for their faith.

Alarmed at this onslaught, an old man who lived on the aforesaid mountain climbed to its peak to rescue Miguel Kuroda’s cross from profanation. He took the cross down and buried it, no doubt as discreetly as he could, but the minions of the shogunal terror sniffed it out, dug it up, and burned it on that very mountaintop, perhaps precisely where it had long stood.

That cross had been the old man’s companion. Mornings he had risen before daybreak and visited it to kneel before it and pray. Perhaps he had known Miguel Kuroda, his erstwhile earthly lord and protector, as a friend and kept him in mind as he knelt before that cross in prayer. Now both Miguel and his cross were gone, with only the ghosts of memory there to console the old man.

Yet he continued to rise before dawn and climb to that spot to visit with his Lord above and pray.

As he prayed, perhaps he saw in his memory the faithful souls of Akizuki scourging themselves bloody as they had often done when they climbed that Calvary in penitential sacrifice. Perhaps he saw others puffing with the strain of heavy stones on their shoulders, burdens they would carry up that mountain for love of Christ to share in the weight of their own sins. Perhaps he saw the bereaved bringing their silent griefs to that mountaintop to be close to their God and listen on their knees for his voice as their own Lord and Savior had done. History leaves no clue to the old man’s private thoughts.

But it does tell us this:

One morning, he was given a sign. Rising before daybreak as usual, he went out to pray at his spiritual haven to be met by a marvel: something like a brilliant, translucent ember shining where the cross had stood, resplendent, framed within the predawn darkness, while the mundane props of this material world could be seen in the distance behind it. Nor did this resplendent vision flash away to leave the old man wondering if he had ever really seen it — no, it lingered for “a great space of time,” giving him ample opportunity to ponder it, to test its reality and consider its meaning.

Consoled, the old man found the strength to carry on. Surely this sign was not meant to vanish in the memory of one lone old man who lived high up on a mountainside.

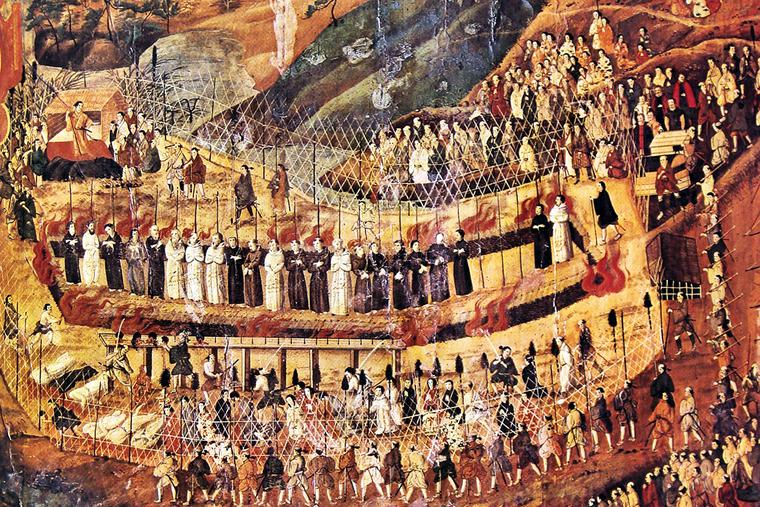

Indeed, come Holy Saturday evening in the Year of Our Lord 1616, a great fire appeared on the mountaintop, a blaze bright enough to be seen for miles around. Many thought that it must be the Christians holding some secret cabal on that peak, perhaps around a bonfire, but it soon became apparent that those benighted souls, Akizuki’s dispossessed Catholic faithful, were there among them gazing up in wonder at the spectacle: a plainly supernatural fire, and in its center a resplendent cross of the same size that Christ’s own would have been, displaying, as many attested — both Christian and pagan — the title that had hung above the Redeemer’s head, its lettering visible through the distance.

Nor did this dazzling vision flash away, but — as the old man’s had done some two years earlier — remained, steadfast, an undeniable fact, a reality, a sign lingering for two unearthly hours on that sacred mountaintop where so many earnest souls had emptied the burdens of their hearts into the open, loving hands of a grieving God.

Whose hands returned the measure of their prayers, their sufferings, their sacrifices a hundredfold on the very Eve of Easter, the 29th Easter since Miguel Kuroda Sōemon Naoyuki felt the cool baptismal water wash away his sins and his old self to give him life anew.

A gift he had striven with all his might to give to every soul that he could reach, like the angel of the Lord who appeared in the sky above the shepherds to proclaim: “Be not afraid; for behold, I bring you good news of a great joy which will come to all the people” (Luke 2:10).

Would that the Tokugawa tyrants themselves had been in Akizuki to see the dazzling proof of that good news — and scotched the martyrdoms that soon would follow.

Luke O’Hara became a Catholic in Japan. His articles and books about Japan’s martyrs can be found at his website, kirishtan.com.