18th Sunday in Ordinary Time — Foolish Men

SCRIPTURES & ART: The wise man is the man who lives right before God.

In the Bible, “wisdom” and “foolishness” are opposites. But they have nothing to do with education, with “book learning.” Wisdom — which was a movement in the broader ancient Near East — was concerned with living successfully and properly. In many ways, it envisioned ordinary common sense, which is why many of the maxims one finds in, say, the Book of Proverbs, also have counterparts in the literatures of other ancient Near Eastern cultures.

But Israel never touched anything which it did not reshape by its core and foundational identity, i.e., that God had chosen Israel and made a covenant with it. If wisdom, then, was about living successfully and well then, for Israel, one could do neither without God.

The wise man is the man who lives right before God. And, as the Psalmist observes, “The fool says in his heart, ‘There is no God’” (Psalm 14:1).

That insight is very much apparent in today’s Gospel.

By contemporary Western standards, the rich man was prudent and entrepreneurial. He had a “bountiful harvest” that he saw provided him security. His was a world in which no small measure of security was to be found in something to eat, because people had experience of famines, droughts, locusts and other pestilences, in an era when “reliable” global supply chains did not exist.

The rich man’s overflowing harvest was greater than his ability to store it. He reconstructs his barns and silos to accommodate that bounty.

Then, he decides to rest and kick back. Having had a windfall harvest and made provision for its storage, he wants to relax, to “eat, drink and be merry.”

Can you blame him?

God apparently does.

God calls him a “fool” — with everything that means for ancient Israel. Why? Because, in assuring his security, he forgot about God. He assume he was in control and that he did a pretty good job taking care of things.

God reminds him that he isn’t in control. Amid all his material goods, he will die tonight.

Matthew reminds us (6:27) that, no matter how much you worry, you can’t add a minute to your life. Luke today teaches us the converse: even if you do everything “right” (at least by the world’s standards), you also are not in control of your life.

Control, of course, has always been a human temptation. The whole “choice” movement claims the ability to “control” one’s life even includes ending a baby’s, and some want to pretend that’s even your “right.” One suspects our Lord would tell those folks the same thing he told the rich man.

Our rich man has done enormous things, but a blood clot the size of a pencil tip can obstruct blood flow and finish him off. He might lay down tonight with visions of wheat bushels dancing in his head … and never get up.

He was diligent. He was prudent. But he acted as if “there is no God.” Maybe not like a raving, ideological atheist, like a Vladimir Lenin or a Chinese Communist. But, to all intents and purposes, he was what Vatican II called a practical atheist [Gaudium et spes 19] — i.e., someone who lives a life in which God is practically absent. Such persons may even call themselves “Christians” (and no doubt our rich man considered himself a good “Jew”) but the fact remains: he organized his life as if he was totally in control and God was practically absent. He acted as if he was self-sufficient, especially by virtue of his material assets (and his “wise” provisions for them) but his self-sufficiency, goods and wisdom all come crashing down when confronted with the truth of his mortality.

In the medieval play “Everyman,” the protagonist is a person about to die. Face-to-face with his mortality, he looks for companions to accompany him. But friends and relatives and goods all bow out. Goods refuse, saying the man’s inordinate love of them would be to his judgment, that he would fare better had he parted with some of them. Tellingly, goods admit to being somewhat like a thief — after having beguiled a man by their possession, they now leave him empty-handed to go in search of his heirs to tempt. The only companions that might be willing to go with Everyman are “good deeds” but, oppressed by sin and devoid of grace, they cannot move without a detour first to the confessional.

Our rich man has assured his future by earthly standards, but not his eternity by God’s standards. That is why he’s a “fool.” He’s worked like a horse … and someone who did nothing will get it all. He has shown hands full of material riches to man. Can he show hands full of spiritual richness to God?

If he can’t, he’s a fool. He remains a fool, even if he’s one whose heirs have a big inheritance tax bill coming in the mail.

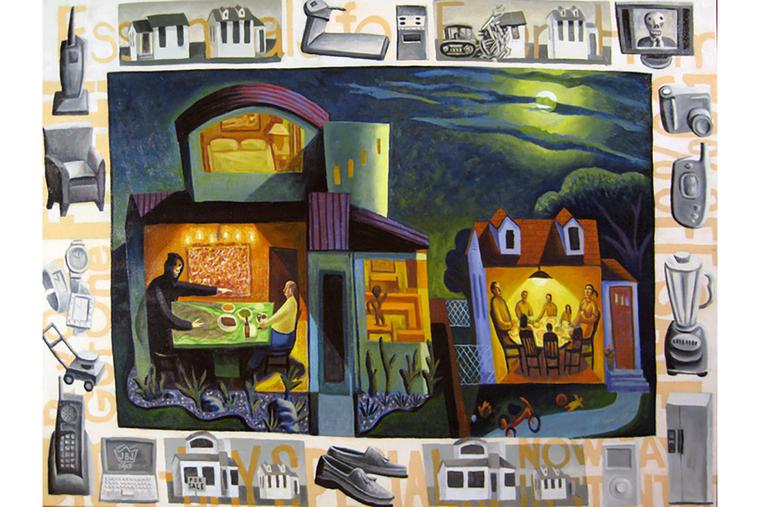

Today’s Gospel is illustrated by a modern Central Texas artist, James Janknegt. His illustration of today’s Gospel captures its essence.

We see two houses. The rich man lives in the house on the left, a poor family in the house on the right. (Left and right have Biblical significance). The rich man’s house is obviously bigger: like the barns of the Gospel’s rich man, our rich man has torn down his old house to build a McMansion. That is apparent in the border of the painting, starting on the upper left, where two similar houses stand. But, in Shania Twain’s immortal words:

All we ever want is more,

A lot more than we had before,

So take me to the nearest store.

So, instead of going for a neighborhood walk, the rich man installed a treadmill (and a new range) and bulldozes his old house to make way for his “stuff.”

George Carlin once observed, “The whole meaning of life [is] trying to find a place for your stuff. That is all your house is: a pile of stuff with a cover on it. Your house is a place to keep your stuff while you go out to get more stuff.”

As we see from the painting’s border, our rich man has been diligent in getting more stuff for his bigger house: TV, camera, phone, appliances, gadgets.

But the two houses stand in stark contrast. The rich man lives in spacious quarters, two voluminous levels with what even looks like a barn silo on the right side. We don’t see the poor family’s upstairs, though it is suggested by the two dormers.

The rich man’s dining room has artwork on the wall and a multi-light chandelier. He also clearly has no guests except that this night (note the moon in the sky): the Grim Reaper has come to sup with him and the rich man appears to have forgotten to buy a very long spoon.

The poor family also has guests, but the guests are the family, since every family is by nature a communio personarum. Nine people seem to be gathered around that table, under a basic light fixture from Home Depot.

The poor family’s house has signs of life around it: a tree on its right, children’s toys in the front yard. The rich man’s McMansion is neatly landscaped (not unlike so many prim and proper McMansions) — albeit with cacti — while the messy signs of kids are conspicuously absent. His sterile landscaping matches his sterile house: clearly “reproductive justice” to assure one’s lifestyle was practiced there! No basketball hoops in that yard!

The border of the painting completes the Gospel. There’s a comfortable pair of empty shoes there. It reminded me of Tolstoy’s story, “Where Love Is, God Is.” In the story an angel, his celestial glory hidden, is doing penance in the shop of a Russian cobbler. (I’m not going to get into the theological absurdity of that). A rich man had ordered high leather boots, but the angel sewed soft slippers. The cobbler was distraught, convinced his apprentice failed him and exposed him to pay for ruined fine leather he could not afford. But the rich man’s servant came, saying his master no longer needed boots because he had died in his sled. He needed funeral slippers instead. As the title asks: What do men live by? “I have learned that all men live not by care for themselves but by love.”

Next to the empty shoes now stands the rich man’s house with a “for sale” sign in front of it. His goods will now tempt a new master. One wonders whether our rich man ever took a walk to his neighbor (how many of us even know our neighbor?) as opposed to one on his treadmill. Three weeks ago, a lawyer worried about his salvation asked, “Who is my neighbor?” Did that question ever trouble our rich man? If it didn’t, did his salvation?

Today’s Gospel situates the problem of self-sufficiency independent of God in an agricultural setting. James Janknegt’s painting applies the Gospel lesson to modern living circumstances. But the question remains the same. It’s not, “Am I rich or poor?” It’s, “Am I a wise man or a fool?”

- Keywords:

- 18th sunday in ordinary time

- scriptures & art