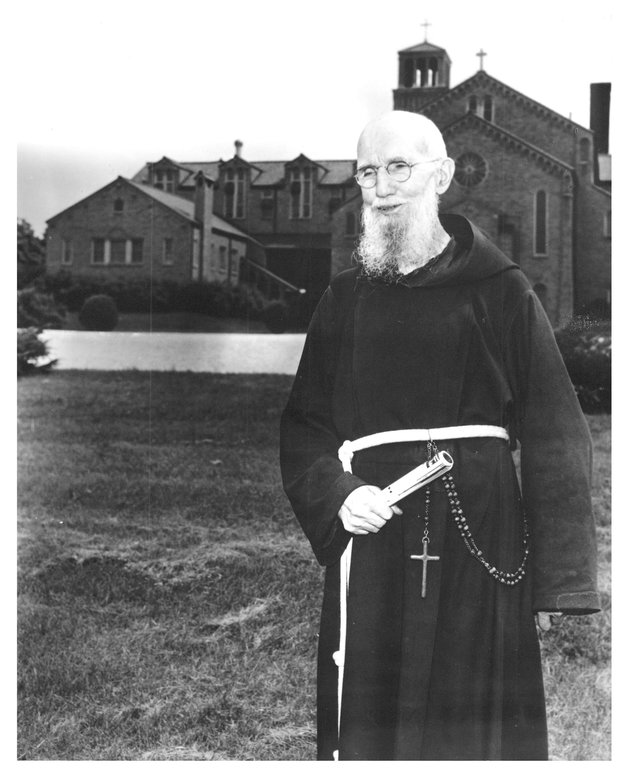

Holy Healer: The Remarkable Life of Father Solanus Casey

The Capuchin priest will soon be beatified.

DETROIT — During his life as a Capuchin, Father Solanus Casey was known as a doorkeeper and miracle worker. Now, as thousands of devotees around the world prepare to celebrate the 60th anniversary of his death, a miracle cure attributed to his intercession was just approved by Pope Francis, clearing the way for his beatification in Detroit later this year (date for the beatification has not yet been decided).

“He has such an interesting character that makes people feel comfortable,” said Brother Richard Merling, vice postulator of Father Casey’s cause for canonization. “People are drawn to him by his simplicity of faith and prayer.” Brother Richard estimates some 100,000 people visit the Solanus Casey Center in Detroit each year, including many from Canada, Europe and Central and South America.

During this writer’s recent visit, a steady stream of visitors entered the doorway. They are still coming — ringing at the door of Father Casey’s heart — to ask his intercession.

As he loved to pray, “Blessed be God in all his designs.”

Deliberations for his cause for canonization began shortly after his death in 1957, followed by the official archdiocesan investigation in 1983. Holy Name Sister Anne Herkenrath of Seattle is the great-niece of Father Casey and was present at the exhumation of his body in 1987. She described to the Register the hot July morning in Detroit when his casket was lifted from the gravesite at St. Bonaventure Monastery and water began to drain from the inside.

Dreading the worst, those present followed as the casket was carried and laid in the chapel. Then, as the lid was lifted and the incorrupt face of her great-uncle appeared, she said, “All I could think was ‘awesome.’ It was perfectly intact and recognizable. He had a terrible skin disease for a good part of his life, but his legs were smooth and white, and the flesh was still there — no sign of the disease.”

Providentially, the miracle paving the way for the priest’s beatification was the curing of a woman who suffered from a genetic skin disease. She was instantly healed while praying at the tomb of Father Casey in Detroit.

A Holy Life

Father Casey was born Bernard Francis Casey Nov. 25, 1870, on a Wisconsin farm. Known as “Barney,” he was the sixth of 16 children born to Irish immigrant parents, and early on, he learned the practical skills of farming and a strong devotion to his Catholic faith. As a teenager, after crop failures reduced the family’s income, he forewent high school to work part time on a log boom, as a prison guard, and later as a full-time streetcar conductor in the burgeoning city of Superior, Wisconsin.

He loved the pioneering adventure of the streetcar industry and considered making it a career. “But one day he had a profound experience that changed his life,” explained Capuchin Father Dan Crosby during a recent interview at the Solanus Casey Center. “He literally stopped in his streetcar tracks when he came upon a woman who had been stabbed to death by a drunken sailor. It was then he realized there was more you can do to bring hope and salvation to the world than just running a streetcar. So he followed through on a thought he had had for a long while and decided to become a priest.”

Father Casey entered the seminary in Milwaukee, but struggled with German and Latin and the rigorous academics. With poor grades, he was advised to return home and consider becoming a Capuchin. Praying for light during a novena in honor of the Solemnity of the Immaculate Conception, at the conclusion of Mass on the ninth day, he heard a clear interior voice: “Go to Detroit.”

He arrived at the Capuchins’ doorstep in Detroit on Christmas Eve 1887. Eight years later, he was ordained as a “simplex priest,” without faculties to hear confessions or preach homilies.

Designated the doorkeeper, he accepted the subservient role and was assigned to Sacred Heart Friary in Yonkers, New York. There, he welcomed only a few visitors each day, but soon dozens appeared, as word spread of his comforting words and powers of healing.

Healer of Hearts and Limbs

Although he spent the greater part of his 70 years as a Capuchin in Detroit, Father Casey also served at Our Lady of Sorrows in New York City, Our Lady of Angels in Harlem, St. Michael’s in Brooklyn and St. Felix Friary in Huntington, Indiana.

“We’re actually sitting in the very place that Solanus met with people,” Brother Richard explained, scanning the entryway of St. Bonaventure Monastery, now connected to the Solanus Casey Center. Brother Richard in his youth had visited the future saint in the same room. “In those days, chairs lined the walls,” he recalled, “and people took turns coming up to Solanus at his desk and telling their stories.”

He described Father Casey’s gifts. “Sometimes people would walk in while he was busy with someone else, and he would turn to them, not knowing anything about their problems, and say in his high-pitched voice, ‘Oh, don’t worry. Everything will be all right with your loved one at the hospital. Go and see them now.’ And then they would leave and find their loved one healthy.”

Recalling another incident, he described a young couple whose 6-year-old son was unable to walk. After the mother finished speaking with Father Casey, the priest turned to the boy, seated in his father’s lap, and said, “Come over here, little boy.” Concerned, the mother whispered, trying to stop him. But the boy stood up and walked.

Apparent miracles like these were common, and, in obedience to his prior, Solanus recorded the instances daily in notebooks, now displayed at the shrine. Among the other items displayed is his violin.

“He liked to sing and to play the violin, and did neither of them well, but it didn’t stop him,” Father Crosby said, explaining Solanus’ weakened voice from childhood diphtheria and his rudimentary self-taught violin skills. Father Crosby lived with Father Casey in 1957 and recounted a musical memory: “On Christmas night, I heard this squeaky noise coming from the public chapel, and I opened the door to see for myself. And there, up in the choir loft, was Solanus, playing Christmas carols on his violin for the Christ Child. No one heard or saw it but me. So it shows how he never did anything to appear holy or impress people.”

Without pretense, Father Casey was able to convince even the hardest hearts, including that of Edward Kraber, a staunch anti-Catholic Mason, whose company made a donation to the Capuchin Soup Kitchen and whom Father Casey soon persuaded to be his driver to collect food donations at a farm near Detroit. Several weeks later, hearing the news of his conversion to the Catholic Church, Kraber’s astonished niece asked, “How did it happen?” Grinning, he replied, “Oh, it’s that damned Irishman, Solanus.”

The Capuchin Irishman’s disarming authenticity was also revealed at family events in Seattle, where the Casey clan had since relocated. Sister Anne was 15 when she first met her great-uncle. She had grown up hearing of his widespread reputation as a mystic and always wondered what he was like.

“But then he played ball with us, and he ran down onto the dock and jumped into the boat,” she said. “And I realized that he was just a normal human being, with a special grace from God.”

Jennifer Sokol writes from

Shoreline, Washington.