The Fight Between Advent and Carnival

Let’s let Advent be Advent and not an anteroom to Christmas.

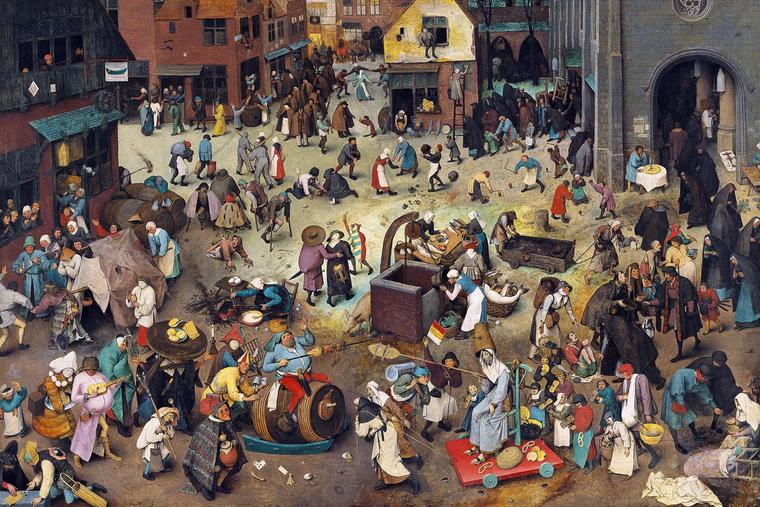

Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s “Fight Between Carnival and Lent” is among the more famous paintings in art history. It depicts a joust between partisans of Mardi Gras and Ash Wednesday, as the two days and camps come together, clashing in the transition from the gaiety of Carnival to the discipline of Lent. The lines are clear.

We need a contemporary Bruegel to paint the “Fight Between Advent and Carnival.”

On the other hand, he might produce a very postmodern piece of art: a blank canvas.

In the Washington area, Christmas trees start going up on Thanksgiving weekend and start coming down sometime between Dec. 27 and the first days of January. By noon last Saturday, my son Karol and I drove past at least four cars with trees tied to their roofs.

I, in turn, am the odd duck around here. Since Advent 2022 is as long as it can possibly be, a tree bought on Thanksgiving Saturday will be nearly a month old by Christmas and likely shedding needles. I never get my tree before the last weekend before Christmas, sometimes even later. By that time, most of the “cut-your-own” tree farms in Virginia and Maryland have closed and, at the few I regularly patronize, I often get the look of “well, where have you been?”

My “last minute” tree buying is not, however, driven by procrastination nor the desire to keep the tree fresh until Christmas. I get equally strange looks after I finally take the tree down. Trying to keep the old custom of leaving the tree up until Candlemas (Feb. 2), I have long passed the date when my neighbors and Fairfax County both thought the Tannenbaum should have been on the curb.

Every year, I also hear from readers who ask whether Advent is still a “penitential” season. I have to say, “it depends.” For the canon lawyers, No. 1250 in the Code of Canon Law says “[t]he penitential days and times in the universal Church are every Friday of the whole year and the season of Lent.” Since 1966, the Catholic bishops of the United States privatized (and, arguably, de facto eliminated) the penitential nature of all but the seven Fridays that fall within Lent and the Paschal Triduum. That leaves Lent alone as a theoretical “penitential season,” though the number of parish social activities — especially in connection with St. Patrick — might make one ask about how consistently contrite the time is.

I would still argue that Advent is penitential, even if the canonists say otherwise, because of its nature. We are preparing for the coming of Christ, and Christ came because we were sinners. The one thing that necessitated his coming then, the one thing that impedes his coming now, and the one thing that will be judged when he comes again, is sin. One would, therefore, be hard-pressed to articulate a coherent theology of Advent that evades the truth we say we believe every Sunday: “For us men and for our salvation, he came down from heaven and was born of the Virgin Mary.”

So, what’s that got to do with Thanksgiving Christmas trees? A lot.

Preparation normally involves a “looking forward.” Preparation is as important — and in some ways as “fun” — as what we are preparing for. Half the excitement of going on a date is getting ready. But apart from the pleasure we get from anticipation, preparation is also important because it shows we take what we are preparing for to be important. All the preparations that go into a wedding, for example, are not (or hopefully shouldn’t be) dictated just by the calendar of the reception hall’s availability. This is an important event, and it deserves preparation.

Our practice has flattened Advent. Instead of Advent being the “now” that leads us to Christmas “tomorrow” (or in however many days, as kids used to count down), it has become a kind of extension of the Christmas (oh, pardon me, I keep using the “C” word — I meant the “holiday”) season. Indeed, modern Advent is somewhat schizophrenic: the multiple “holiday parties” that compete for niches within it are anticipated Christmases, but the ongoing buying frenzy still points to Dec. 25.

What’s wrong in this picture is perhaps why a modern Bruegel might have a blank canvas for the “Fight Between Advent and Carnival.”

Advent used to be penitential. It used to be marked by parish retreats and other spiritual exercises in preparation for Christmas. Dec. 24 used to be a day of fast and abstinence: the reason traditional Christmas Eve meals among Poles (Wigilia), Italians, and many Spanish-descended cultures are meatless stem from that.

Because Advent was penitential, Christmastide and the time following it — Carnival — was festive. In more agricultural societies, where winter reduced the daily workload, the time after Christmas was a time of celebration and festivity. The joy of Christmas spilled out across what used to be the “time after Epiphany” until the arrival of Lent finally shut it off.

Mainstream American culture has performed a switcheroo: Advent’s become our pre-Christmas party season, while Carnival has disappeared (except, perhaps, in New Orleans and even there, likely for only a few days).

Do moderns have Carnival? No: festivity is in theory always available. But the truth is that if sometime is always there, it is usually taken for granted. Because moderns don’t say an occasional “no” to festivity, is this perhaps why their celebrations are so anemic?

Consider the denouement of December. After a month of “holiday parties” culminating in Christmas, the octave week practically becomes a down time. Kids and some parents have the days off. Sometimes a note of preparation intrudes as people make ready for New Year’s Eve. Otherwise, Dec. 26-31 is largely quiet, often populated by exchanging things that one received Dec. 25 that aren’t really wanted. (Dec. 26 sometimes has the makings of a junior Black Friday).

A final crescendo leads to the celebration of “New Year’s Eve” (or, for the woker-than-thous not wanting to offend, “First Night”). But let’s be honest: it all peters out rapidly after the last champagne flute is emptied and the last noisemaker blown. For most Americans, by 3am on Jan. 1, it’s all over. (The Catholic bishops abet this with their “sometimes-it’s-a-holyday-sometimes-it’s-not” approach to Jan. 1). Soon come down all the “holiday decorations” and Americans seem to “settle in for a long winter’s nap.”

Whereas our ancestors once were energized by the joy of Christmas that carried them all the way to Ash Wednesday, moderns, worn out by a premature Christmas that preempts a flaccid Advent, appear drained of any long-term spirit of celebration.

So, let’s let Advent be Advent and not an anteroom to Christmas. True celebration draws a line between celebration and not-celebration. It’s the blurring or erasure of that line that produces our caricature of “celebration” — our rote “holiday” ennui.