Second Sunday of Easter — Divine Mercy Sunday

Divine Mercy receives its ultimate expression in the seven sacraments

The Second Sunday of Easter is also Divine Mercy Sunday. It was once called “Dominica in albis,” (Sunday in white) because it was on the eighth day — the perfect, eschatological day — that the newly baptized at the Easter Vigil finally took off the white robes they were given at the baptismal font.

Today also ends the Easter Octave. Today is the Second Sunday of Easter — the Sundays that follow Easter are Sundays of Easter, not Sundays after Easter, to underscore that the “joy of the Resurrection fills the whole world” so pervasively that, through Pentecost, this is the Church’s one great feast that gives meaning to the whole of the Christian year and life.

The Gospel of the Second Sunday of Easter is always John 20:19-31, which contains four key elements:

- John’s account of Jesus’ first appearance to all his Apostles (minus Thomas) on Easter Sunday night;

- Christ’s wish of peace and gift of the Holy Spirit in words that the Church has understood to be the institution of the sacrament of Penance;

- The observation that Thomas was absent; and

- Jesus’ appearance to his Apostles on the Sunday following the Resurrection, i.e., today, when Thomas is present and professes his faith.

The Apostles are in the Upper Room and scared. They still don’t know about their own safety after the judicial murder of Jesus on Friday. Now there are all sorts of stories going around about Jesus’ Tomb being empty, his body gone and him appearing to individuals. No doubt they also feel a certain guilt, having either run away or denied Jesus when he needed them most.

Jesus appears to them. He wishes them shalom. It’s not simple “peace.” It is peace that comes from a profound reconciliation, settling of accounts and forgiveness. That is what Jesus’ whole life (especially during the past three days) has been all about. He now returns to those upon whom he had planned to build his Church, and launches them into this new era.

He breathes on them. There is a deliberate parallel to Genesis 1:2, where the Spirit of God moves over the waters. That same Spirit, breathed on to the world at creation, is now breathed on to a new world that has just been created at the garden tomb as the new principle of its life.

That new principle of life does not erase the old world or its history. In that world, man sinned. In the new order of creation, the Spirit is given to fix that old wound: if sin is what warped creation, the forgiveness of sins is what Jesus offers for that new world.

The Church has always recognized in John 20:21-23 the institution of the sacrament of Penance. The mission to overcome sin was given by the Father to Christ. He made that possible by dying on the Cross and rising from the grave. Jesus makes overcoming all sin possible, but there is no generic sin. There are only your sins and my sins. They have to be overcome by personal encounter, but we human beings are stuck in space and time (which Jesus apparently already isn’t, having entered through the locked door). So his mission to “take away the sins of the world” has to be shared, passed on to others who, in this place and this time, will declare that same “peace” Jesus did that first Easter night. That is the role of the Apostles, the role of priests in the sacrament of Penance. “Why do I have to confess my sins to a priest?” Because that’s how Jesus himself, the source of your forgiveness who respects your place in space and time, set it up. (Now, are you really sorry for your sins if you don’t want to accept forgivness on the terms he set up?) He made it possible, but somebody has to make it real, in the lives of John and Mary and Linus and Perpetua. That’s the priest’s Christ-given job.

As noted above, John 20 has always traditionally been the Gospel for this Sunday. When St. John Paul II established today as “Divine Mercy Sunday,” acceding to the Lord’s wish expressed through St. Faustina Kowalska, it was serendipitous (and Providential) that the Church had always used John 20 for the Gospel reading of the day. God’s mercy and the forgiveness of sins receives its ultimate expression in the sacraments: in Baptism, where we become children of God and heirs of heaven, and in Penance where, despite our treasons and our failings, the Father is always ready to take his prodigal sons and daughters back. That is why St. Faustina says that Our Lord attributed a special privilege to receiving the sacrament of Penance (at some point on or after Good Friday) and Communion today:

On that day the very depths of My tender mercy are open. I pour out a whole ocean of graces upon those souls who approach the fount of My mercy. The soul that will go to Confession and receive Holy Communion shall obtain complete forgiveness of sins and punishment. On that day all the divine floodgates through which grace flow are opened. Let no soul fear to draw near to Me, even though its sins be as scarlet (Diary of St. Faustina Kowalska, no. 699).

People have a choice to accept God or reject him, but rejecting him does not mean God goes away and people are free to do as they want. Today, Jesus offers us peace through his mercy. If we don’t want that peace, i.e., we don’t want what Jesus died for, what the past Triduum and Octave have been all about, then it means we want the old world in which sin reigned — one subject to justice, under whose imprint we then also voluntarily subject ourselves. As Sr. Faustina records Jesus telling her:

Write: before I come as a just Judge, I first open wide the door of My mercy. He who refuses to pass through the door of My mercy must pass through the door of My justice …” (Diary, no. 1146).

All this requires faith, faith to acknowledge that this Man died and rose, conquering sin and death. That he is not just an inspired teacher or a politically-driven Messiah to whom some people attached their wagon carts, but the God-Man who, because of what happened on that first Easter, has changed the whole direction of human history in a process that encompasses all peoples of all times that will only end with the End of the World. That, because of Easter, nothing will ever be the same again.

That is what Jesus wants when he asks us not to persist in unbelief but to believe. It is what Thomas was initially not wont to do. In some ways, Thomas is a thoroughly-modern man. “C’mon, guys? Some dead guy rising? You been sippin’ the seder wine? We bet on the wrong guy, he got nailed, it’s over, now let’s move on.”

That doubt is contending with faith — otherwise, why would Thomas have come back that next Sunday? If he really did not believe, he would have packed up and gone home, perhaps back to Galilee. He didn’t. What was he hanging around for? There is a spark of faith there — he’s doubting Thomas, not disbelieving Thomas. And that spark is enough for God to kindle, as we see in today’s Gospel. Kindle with the tangible proofs that now make Thomas (and the other Apostles) the sources of credibility backing up our own faith, of we “who have not seen but believed.”

Duccio di Buoninsegna

Today’s Gospel is illustrated in art by the 14th-century artist from Siena (140 miles north/northwest of Rome), Duccio di Buoninsegna. It was one panel of approximately 80 that made up the Maestà, a 16-foot-by-16-foot altarpiece for the main altar in Siena’s cathedral. The work is tempera on wood, meaning it took colored pigments and made them adhere to the wood using some other medium, typically egg yolk.

The panel was deliberately designed with today’s Gospel in mind, depicting Jesus’ first Johannine appearance on Easter Sunday. How do we know? There are 10 Apostles present, symmetrically five on each side of Jesus. Thomas “was not with them” and Judas had hung himself. Jesus stand in front of a door still locked, through which he has passed. [After all, Jesus is “the Way” (John 14:6) and “the Gate” (John 10:9) through whom he has already told his Apostles that those who would follow him really must pass].

Jesus’ hand is raised in blessing (and not unlike absolution). His wounds are clear, at least on his feet. The hands of the four Apostles in the foreground — the only ones whose hands are visible — in turn gesture toward the Lord, almost as a kind of affirmation of faith. Can we suggest that that the gray-bearded older man on his right, in blue and green, is Peter and the young, unbearded man on his left, in reddish hues, is John?

The style of the painting has both Byzantine elements in its icon-style as well as late medieval Gothic stylization. This is in keeping with the influences of East and West in what is today Italy.

The Maestà was taken apart in 1711, with various components (including this one) on display in the Siena Cathedral museum.

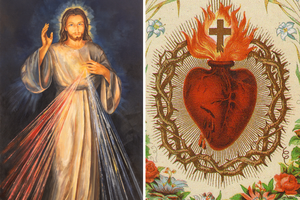

Divine Mercy Image

In conjunction with the Feast of Divine Mercy, Our Lord charged St. Faustina Kowalska to have the image of Divine Mercy which she saw painted. Eugeniusz Kazimirowski painted the first version, which was displayed at the Shrine of Our Lady of Ostrabrama in Vilnius, Lithuania, on April 26-28, 1935. The painting was later kept at St. Michael’s Church in Vilnius, until the Soviets closed the church in 1948. It was later hidden at Vilnius’ Dominican church, then later in a church in Belarus, only to be returned to Lithuania and returned to public view as communism was falling.

According to St. Faustina (Diary, no. 47), Jesus instructed her to promote veneration of this image of Jesus’ Divine Mercy, ultimately throughout the world.

Paint an image according to the pattern you see, with the signature: "Jesus, I trust in You". I desire that this image be venerated, first in your chapel, and then throughout the world. I promise that the soul that will venerate this image will not perish.

Once upon a time, Catholics had the custom of having religious and devotional images in their home. Why not add this daily reminder of trust in Jesus’ Mercy to your house? (For paintings, see here.)

- Keywords:

- divine mercy

- scriptures & art

- confession

- sacraments