The Earth Is a Planet; Not All Planets Are Earths

PART IV: In the 1800s, the idea of a Plurality of Worlds was challenged by the fact that, just as stars are not all other suns, planets are not all other earths — and that even on those planets that might be other earths, inhabitants might not naturally spring out of the ground.

UFOs, ETs and the Strange History of Other Earths

PART I – PART II – PART III – PART IV

Blockbuster movie franchises, media coverage of UFOs and Navy pilots, and claims about what the discovery of “extraterrestrials” would mean for humankind’s place in the universe all hinge on the idea that our universe abounds in other worlds like our Earth. This prominent idea is commonly associated with scientific progress, dating back to Copernicus in the 16th century. But as this four-part series shows, science in fact has never supported this idea of a “Plurality of Worlds.”

* * * * * * *

In the 19th century science showed how, contrary to long-held assumptions, there was great diversity in the universe of stars (see Part III of this series). At the same time, science spoke up in another way for the idea of diversity in the universe, and against the idea of a Plurality of Worlds. Just as astronomers today recognize that most stars are not just like the sun, we also recognize that most planets are not just like Earth.

Contrary to astronomers of two centuries ago, we do not expect to find an extraterrestrial civilization on Jupiter, or on the sun, or anywhere else in the solar system. We may yet find life of some sort some place within it — in the cold, black waters under the ice of Saturn’s moon Enceladus, for example — but regardless, the solar system outside of Earth is largely, if not wholly, lifeless.

William Whewell: No Intelligent Life on Jupiter

The historian of science Michael J. Crowe of the University of Notre Dame has suggested that William Whewell was the first person to envision this lifeless solar system. Whewell was Master of Trinity College of Cambridge University. In 1853 he anonymously published Of the Plurality of Worlds: An Essay, attacking scientifically the idea of a universe widely inhabited with intelligent life.

Crowe points out that a key argument of Whewell’s was applications of the inverse-square law as it relates to gravitational force, light, and heat radiation. This law says that if planet B is twice the distance from the sun as planet A, it will receive one quarter the heat and light from the sun, all else equal. Thus, were the Earth a little closer to or further from the sun then the amount of heat and light it would receive would be significantly changed. Crowe argues that Whewell was one of the first people to consider the idea of a “habitable zone” around a star (implying that most of the region around a star is generally not so habitable) — an idea he put forward in the Essay.

Whewell also used geology to argue against widespread extraterrestrial intelligence. Crowe notes that Whewell had been elected president of England’s Geological Society and that …

… Whewell’s argument was that evidence for the age of the Earth showed that throughout most of Earth’s history it had been bereft of intelligent life, which suggested that the Creator’s plan for the cosmos was capacious enough to leave vast regions of it lacking [intelligent extraterrestrials] for long periods of time.

Whewell did not rule out the idea of lower life forms within the solar system. For example, he speculated on life existing on Jupiter, writing that Jovian life forms might be “aqueous, gelatinous creatures; too sluggish, almost, to be deemed alive, floating on their ice-cold water, shrouded forever by their humid skies.”

Crowe argues that the scientific evidence for planets being diverse, and not merely other earths, was present long before Whewell. The great difference in the sizes of Earth and Jupiter had been known for more than two centuries. Isaac Newton, whose physics of inertia and universal gravitation supplanted Descartes’s vortices (see Part II of this series), had included in the third edition of his Principia (1726) calculations showing the substantial differences in the masses, densities and surface gravities of different solar system bodies. Such differences might have provided reason to suppose that the planets were sufficiently unlike our Earth to be devoid of intelligent life.

Astronomers prior to Whewell did recognize planetary diversity. However, that recognition was limited, and inclined toward a Plurality of Worlds. Consider Whewell’s friend John Herschel, the son of William Herschel (whom we met in Part III), and one of the more prominent astronomers of Whewell’s time. Prior to Whewell’s 1853 Essay, John Herschel had discussed how much more solar heat Mercury receives than Uranus, how much stronger gravity must be on Jupiter than on Earth, and how the density of Saturn is so much less than the density of Earth that Saturn “must consist of materials not much heavier than cork.” Yet he still presumed that all the planets must be inhabited, much as his father presumed the sun to be inhabited.

When Whewell came out against a Plurality of Worlds, Herschel wrote to him that, “though somewhere I have myself stated that taken in a lump Saturn might be regarded as made of cork — it never did occur to me to draw the conclusion that ergo the surface of Saturn must be of extreme tenuity.” Herschel then went on to propose that even were Jupiter an ice-cold sea, it might be populated by intelligent fish who construct crystal palaces in the warmer depths of the seas, and not just by Whewell’s gelatinous creatures.

Of course, today it would be a monumental discovery were we to find on cold Enceladus even one small colony of the most microscopic gelatinous creatures. Planets are indeed diverse: Venus is utterly unlike Jupiter, and yet both are so unlike Earth as to be uninhabitable. The diversity of the solar system goes far beyond what Whewell himself directly envisioned.

Spontaneous Generation

The realization that stars and planets are diverse worlds, and not merely other suns and other Earths, was not the only blow delivered to the Plurality of Worlds idea by 19th-century science. Another blow was against the idea of widespread life itself — against life’s spontaneous generation.

Spontaneous generation was an old idea, dating back to at least Aristotle. For example, people thought frogs could be generated right out of the mud. At the right time, supposedly, one could find frogs in the act of forming, so that parts of them were alive, while other parts were still unliving mud:

Aelianus saith, that as he travailed out of Italy into Naples, he saw divers Frogs by the way..., whose fore-part and head did move and creep, but their hinder-part was unformed and like to the slime of the Earth, which caused Ovid to write thus:...

Durt hath his seed ingendring Frogs full green,

Yet so as feetlesse and without legs on earth they lie,

So as a wonder unto passengers is seen,

One part hath life, the other earth full dead is nye.

Ancient Jewish rabbis discussed whether the earth from which a mouse might be spontaneously forming would be unclean, since Leviticus 11:29 lists mice as being among the various “creeping things” that are unclean. Antony Van Leeuwenhoek, the pioneering microscopist of the 17th century, complained of “respectable and learned men” who told him that eels were spontaneously generated from dew, “in confirmation of which they add, that if no dew has fallen, there will be no eels found.”

Given spontaneous generation, life should be the default for any world — maybe even the sun. But work by Van Leeuwenhoek (who showed that even eels beget offspring) and others undermined the idea of spontaneous generation. By the end of the 19th century science had killed off the idea entirely. (It did not die easily — as late as the 1880s the German botanist Carl Nägeli was arguing that simple living creatures were spontaneously generated all the time, and that higher life forms then evolved from those simple life forms.)

Science has been able to show that life does not just spontaneously pop up on its own. By whatever means life originated on Earth, it is clear that it originated a long time ago, through a process which we cannot reproduce in a lab or find occurring in nature. Science tells us that nothing living on Earth today just spontaneously sprang to life last night; it is all descended from something living here in the past. The fact that life does not easily arise from matter here does not give us reason to think it will arise easily on other worlds, or to suppose it to be the default for any world.

Science’s Challenge to a Plurality of Worlds — and to a very Popular Idea

When Giordano Bruno promoted the idea of a Plurality of Worlds, science was clearly against it, as Johannes Kepler took pains to point out (see Part I of this series). When Bernard Le Bovier de Fontenelle popularized the idea, and it grew to be widely supported by astronomers, science offered nothing to support it, and offered easily reproducible results to question it (see Part II). And well more than a century ago, science again started to directly challenge it by demonstrating that stars are not all other suns (Part III), planets are not all other earths — and that even on those planets that might be other earths, inhabitants might not naturally spring out of the ground.

Since then, science’s challenge to the Plurality of Worlds idea has continued to grow. Science has expanded on Whewell’s point regarding Earth long having been home to no intelligent beings. Indeed, science tells us that, for most of the Earth’s history, it was home to nothing beyond simple, unicellular life. Meanwhile, modern observations of planetary systems orbiting other stars have further illustrated the diversity existing within the universe. We see that such planetary systems often differ dramatically from our solar system. We see Jupiter-sized (or larger) planets in Mercury-sized (or smaller) orbits. We see that half of the planets out there are of a size not found in the solar system.

Note: this diverse universe does not tell us that our Earth is the only earth, and that there are no planets in the universe that are home to intelligent extraterrestrials. The choices are not either

(a) science supports the sort of universe envisioned by Mark Twain in his Captain Stormfield (see Part III) — or, for that matter, the sort of universe envisioned by today’s big comic book/science fiction movie franchises

or

(b) science supports a unique Earth.

Other options exist. A sparsely populated universe, home to widely scattered earths that are not all endowed with intelligent life, may be the option that science best supports.

But if science does not support, and never has supported, a Plurality of Worlds, that means something, for the idea remains as popular as ever. For example, let us return to the story that I employed to begin this four-part series: UFOs, and “UFOs from outer space” being headlines of serious news organizations in 2021 (see Part I).

In a sparsely populated universe, one intelligent civilization finding another amidst the diverse superabundance of uninhabited planets — and then managing to travel through all that to reach the other civilization and buzz its navy with UFOs — would seem rather difficult. From the standpoint of scientific plausibility, would it not make more sense to attribute the UFOs not to extraterrestrials, but rather to... an advanced ocean-floor civilization of mer-people, drawn up from seclusion to confront the Navy because of what human beings are doing to the Earth’s oceans? After all, mer-UFOs involve no vast distances to cover, no problem of life originating elsewhere, etc.

In starting this series, I remarked on people from serious news organizations virtually banging on the door of the Vatican’s astronomical observatory, wanting someone to say something newsworthy about extraterrestrials in light of the Navy UFO story. Well, let them now go bang on the virtual doors of oceanographers for comments on UFOs!

These last two paragraphs are an effort at humor! The best option is that the banging simply ceases. After all, the most scientifically plausible explanations for UFOs are exactly the sort of normal, human, terrestrial, and not newsworthy explanations offered by the “UFO report” released by the Office of the Director of National Intelligence in June 2021.

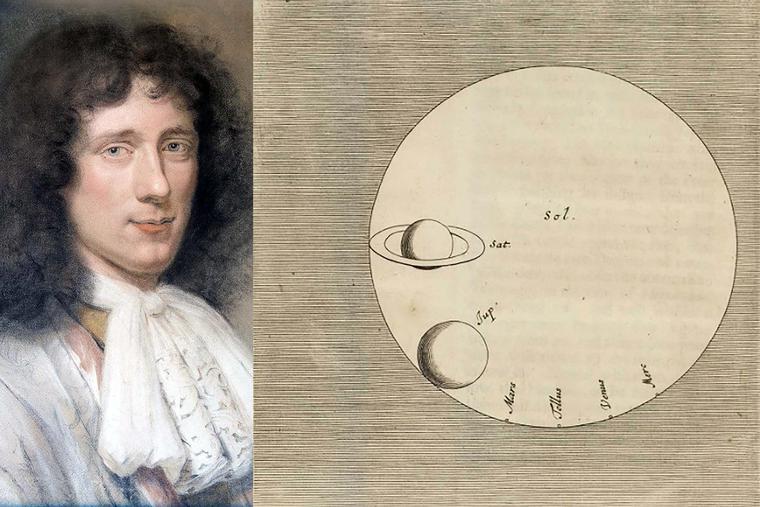

But history shows us that, when the subject is life on other worlds, what is scientifically plausible just does not matter. What matters might be what speaks to our politics, or our religious outlook. It might be just what makes for a great comic book story or movie story, or news story, that will be sure to garner an audience. Were science what matters, the idea of a universe full of other earths would not have survived Johannes Kepler four centuries ago. Kepler, Jacques Cassini (see Part II) and Whewell should be celebrated for being willing to consider the universe that science revealed — and reveals — rather than the universe that everyone, across centuries, has always wanted to see.

Further Reading

Crowe, M. J. (2008). The Extraterrestrial Life Debate, Antiquity to 1915: A Source Book. Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press.

Crowe, M. J. (2016). William Whewell, the Plurality of Worlds, and the Modern Solar System. Zygon: Journal of Religion and Science, 51(2), 431-449.

- Keywords:

- ufos

- extraterrestrials

- other earths