‘Golgotha’: Catholics and the Great War

How prayer and the aid of chaplains was vital in the trenches — and devotion was bolstered on the homefront, too.

“For fourteen hours I was at work yesterday — teaching Christ to lift His cross by numbers and how to adjust His crown. ... I inspected His feet that they should be worthy of the nails ... with maps I make Him familiar with the topography of Golgotha.”

So wrote the First World War poet Wilfred Owen, using the language of priestly sacrifice as metaphor. The 100th anniversary of the Great War’s ending reminds us of the witness of Catholics at the front, especially Catholic military chaplains. In the mud and blood of that four-year “Golgotha,” however, there was also for many a moment of grace, as outlined in Stories of World War I: Faith in Action and Priests in Uniform: Catholic Military Chaplains in the First World War.

The French government had, only years earlier, enacted laws so severe that they forced some religious to seek refuge in Protestant England.

From the outbreak of war in 1914, throughout France, ordinances were passed, reversing many of the restrictions on priests and religious as the French government found itself desperate to enlist their services at the front, particularly in military hospitals.

By December 1914, only months after the outbreak of the war, The Times reported that 87 Catholic priests and 127 nuns had been awarded the French Légion d’Honneur for services rendered to French forces: “Everywhere the priests have been distinguished for their heroism, and their devotion to the patriotic cause is shared by many members of religious orders, both men and women.”

The Paris correspondent for The Times, however, went on to make an even more remarkable statement, namely, that the outbreak of war had seen a religious revival in France.

Other newspapers reported moving instances of the devotion of French military chaplains.

The Daily Chronicle of Oct. 31, 1914, reported the story of a Paris train station full of wounded soldiers, one of whom indicated to a nearby nurse that he needed “to confess very badly.” The nurse wondered if a priest could be found in all the noise and confusion around her. Suddenly another of the wounded who lay there spoke: “I am a priest; I can give him absolution. Carry me to him.”

The nurse hesitated, however, as she knew how badly wounded the priest was and that any movement would involve excruciating pain. The wounded priest insisted. The priest was carried to and placed beside the soldier. The confession did not take long, but when it came to giving the sign of absolution, the priest called the nurse over and asked her to hold up his hand as he began: “Ego te absolvo ...” Shortly after this act, both priest and penitent were dead. The nurse and ambulance man who had witnessed this, the newspaper reported, fell to their knees in prayer.

By January 1915, as many as 2,000 priests were enrolled in the army of France. It was not just that priests gave spiritual aid to the soldiers who fought. Early on in the conflict some of these priests also gave their lives.

Philip Gibb, a British war journalist writing for The Daily Chronicle had this to say about how the life and death of those French priests impacted the troops around them:

“The priest-soldier in France is a spiritual influence among his comrades, so that they fight with nobler motives than of a blood lust. … A young priest who says his prayers before lying down on his straw mattress or in the mud of his trench puts a check upon blasphemy, and his fellows watch him curiously. … It is easy to see that he is eager to give up his life as a sacrifice to the God of his faith. His courage has something of the supernatural in it. … He is careless of death.”

In the circumstances, the piety of French soldiers quickly revived. The Tablet of Feb. 13, 1915, reported of a rosary made of string by a soldier that was being passed down the line as the prayer was said by all in the same trench. When it wore out, the local curé was approached for a “stronger” rosary.

The Cork Examiner reported in May 1915 of a French commanding officer coming across a soldier from the Breton region saying his Rosary in a trench at the front. The officer asked if the man was saying it because he was frightened. The man replied: “No, mon Colonel, because it helps me.” The officer replied that this was the right answer and asked if they could say it together. Other soldiers witnessing the men praying asked if they, too, might join in. Soon the whole trench was praying the Rosary.

At the time, a common saying among French priests was: “The German cannon is worth all the missionaries put together.” It was not just France that was gripped by a religious revival. An English resident of Bruges in Belgium wrote to The Tablet in September 1914 to tell of what he had just seen.

“One of the most impressive sights of this tragic time is that of the incessant crowds of people who tramp in pilgrimage, night after night, along the route of the yearly pilgrimage of the Holy Blood.” He talked of a great number, of parish groups as well as solitary individuals, walking in silence reciting the Rosary. He concluded that “heaven is being besieged.”

At the outbreak of war in 1914, the British army had 23 military chaplains. By the end of the conflict, four years later, 800 priests had ministered to the soldiers, sailors and airmen fighting; 41 of these chaplains were to die in battle. The first priest killed in action was Father William Finn. He was chaplain to the 1st Royal Dublin Fusiliers. He died during the ill-fated Gallipoli campaign.

Although badly wounded upon disembarking on a gangway of a troop transport, Father Finn insisted on continuing to minister to the wounded. Later that day, he was twice hit by sniper fire. He was last seen crouching beside a dying man: The priest was holding his now crippled right arm with his left so he could make the Sign of the Cross over the man as he gave absolution. While doing so, another shot ended his life.

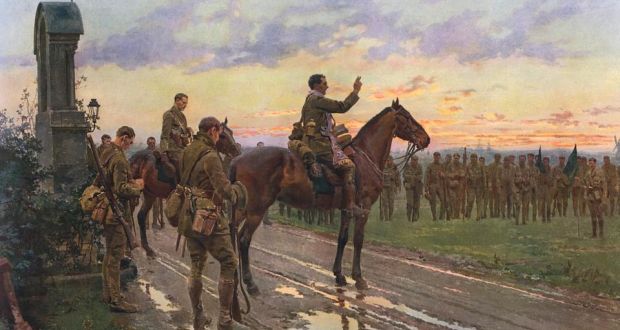

On the Western Front, the first Catholic chaplain to be killed was Jesuit Father John Gwynn, chaplain to the Irish Guards. War correspondents had noted a custom introduced by Father Gwynn just before the soldiers going “over the top” into battle. The priest would have the guardsmen kneel silently for a few moments in prayer, before giving them absolution.

For so many of these soldiers, this was to be their final moment, one of prayer and forgiveness, before they charged into a hail of bullets and bombs that propelled them into another world.

At sea, the first Catholic chaplain to die during the war was another Irish man, the Benedictine monk Dom Basil Gwydir. In September 1914 the hospital ship Rohilla was caught in a severe storm off the English coast. The priest was urged to leave the stricken vessel when a rescue ship drew alongside to evacuate those well enough to board it.

Conscious this would mean abandoning the sick, the priest chose to return below decks to be with the invalids who could not be moved. Soon after, the Rohilla broke up, and all left aboard her were drowned.

Just as the French priests had noted the effect of the “German cannons” on the faith of their fellow French men, there was also the grace-filled impact of the many British Catholics who served during the First World War. After the war’s end, some estimated that as many as 40,000 British military had converted to the Catholic faith during the four years of fighting.

One example was Bernard Berlyn. Before the war he had been an Anglican clergyman; when war was declared, he became a military chaplain. In letters home, he remarked on how indifferent to their Anglicanism even while at the front the Anglican soldiers appeared to be.

In contrast, he noted how devout the Catholic soldiers were. He would watch as these soldiers crowded around their Catholic chaplain for absolution before going into battle. It began to make him ponder on what he termed the “fruits of the two systems,” Anglicanism and Catholicism. Religion for the Catholic was not simply something into which he was born, nor, from what Berlyn observed, was it something merely nominal.

“In the hour of their need they turned to it as naturally as a child to its mother. … I saw in that terrible time something of the real Catholic spirit of the Church, the French, English, Belgians, and even the German prisoners, all receiving the same Sacraments, from the same English priest.”

At this point, Berlyn says: “The scales fell from my eyes, and I saw the Catholic Church as I had never done before.” A month after writing those lines, Berlyn was received into the Catholic Church (he is known to have corresponded with G.K. Chesterton).

Another conversion came through accidentally stumbling upon something holy being offered at the battlefront. On a rainy Sunday, Fusilier David Jones came across a wooden stockade and, looking through a crack in it, beheld what he would later describe as “a great marvel.” He saw two candles and the back of a man dressed in liturgical vestments facing a stack of ammunition boxes covered by a white cloth. Half a dozen men, all of different ranks and battalions, were kneeling. Suddenly, the air was filled by the tinkling of a bell, as mysterious Latin words were intoned. Jones realized later that he had observed the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass. It was like nothing he had witnessed before in his Christian upbringing; Jones would become a Catholic in 1921. That momentary experience of another reality witnessed at the Somme was never to leave the former soldier, who would become a renowned poet, painter and engraver.

Unlike both Lutheranism and Anglicanism, the Catholic faith transcended national boundaries, especially so in Europe. Early in the war, The Tablet reported the story of a dying Prussian Calvary officer. The French officer who came across the enemy officer lying in a pool of his own blood noted that the man produced a Rosary and an image of Our Lady. The dying man was a Pole.

The Frenchman indicated that he, too, was Catholic. At this, the Pole lifted up the rosary, and, understanding his intention, the Frenchman led the Pole in his final recitation of the prayer. At the prayer’s end, the Pole kissed the beads and then offered them to his companion, who also kissed them. Shortly afterward, now smiling, the dying man closed his eyes for the last time.

Strange friend,” I said, “here is no cause to mourn.”

“None,” said that other.

“Let us sleep now ...”

(Wilfred Owen, Strange Meeting)

K.V. Turley writes from London.