Cardinal Gibbons’ Nod To Bishop Challoner

When an Imprimatur is More Than an Imprimatur

The opening page of the Douay-Rheims translation of the Bible contains a curiosity that I’ve never quite been able to figure out. Instead of simply the usual imprimatur/nihil obstat, the copyright page reads:

Approbation of His Eminence James Cardinal Gibbons, Archbishop of Baltimore: We hereby approve of the publication of Messrs. John Murphy Co. of the Catholic Bible, which is an accurate reprint of the Rheims and Douay edition with Dr. Challoner’s Notes. The sacred volume is printed in an attractive style. +J. Card. Gibbons, Baltimore, Sept. 1, 1899.

This is what I find so curious about the imprimatur on the part of Cardinal Gibbons. Not only does the cardinal give his official approval to the work — he okays Dr. Challoner’s notes and remarks, oddly, “The sacred volume is printed in an attractive style.”

Why would a cardinal make such a remark in a place reserved for the fewest words of “nothing stands in the way of printing this book”?

Well, for one thing a Bible should be beautiful. In an age of e-books (and a lack of copyrights), we’ve grown accustomed to words on a screen that we can adjust, and even change the font to suit our fancy.

However, for centuries, the Holy Bible was printed sumptuously—even in the 1960s a “Michelangelo” edition was available which contained the authorized Douay-Rheims translations, along with full-color plates of the religious works of “Il Divino.”

But in the 1970s, a plethora of “Good News” mass-market newspaper-print onionskin paperback editions flooded the Catholic market. No need to look for “an attractive style,” let alone color reproductions of the works of Michelangelo here.

Perhaps Cardinal Gibbons was prescient, however: Donald Jackson and his team of illustrators and calligraphers recently completed, after years and years of painstaking work, the Herculean task of reproducing, by hand, the entire Holy Bible (at least the New Revised Standard Version), in color (and English!), using only medieval materials and techniques. As monks say: “One hand holds the pen — but the whole body works, and aches.”

In April 2015 the final version of this gorgeous, stunningly-illustrated, multi-volume hand-lettered Bible — known as “The Saint John’s Bible” — was presented to Pope Francis.

However, to Cardinal Gibbons’ other brief note: The Saint John’s Bible is devoid of any annotation. Gibbons’ nod to “Dr. Challoner” and his notes raise the question: Who was “Dr. Challoner?”

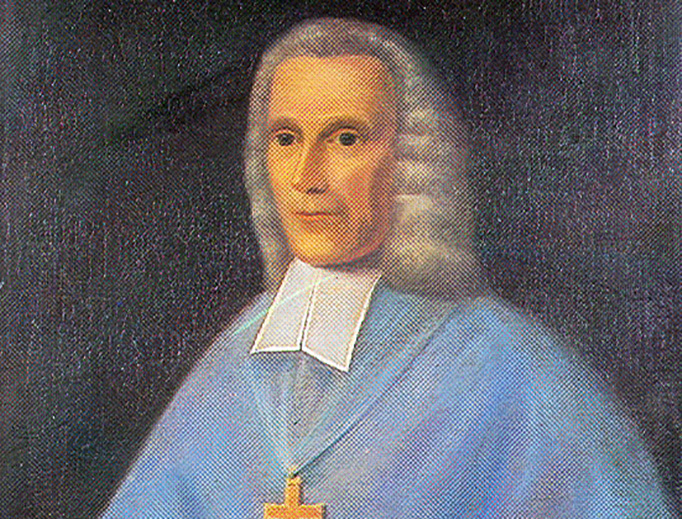

Richard Challoner (1691-1781) was an Englishman who was baptized a Catholic at the age of 13 and almost immediately sent to France since Great Britain was in the midst of one of its greatest (and most deplorable) persecutions of Catholics. Challoner studied and then remained at the College of Douay (also Douai) for the next 25 years. He was successively a professor and vice president of the famous Catholic college. Then, disguised as a layman, he returned to England.

Challoner wrote pious tracts, especially on the saints and martyrs, which he had printed and disseminated at his own expense, and, while in England said Holy Mass among the poor and needy, tending to avoid the wealthy estates of nominally “Anglican” Christians (who were really Catholics in secret).

Challoner’s work in Britain was recognized in Rome and he was named Bishop of Debra — “The Vicar Apostolic of The London District” — though he pleaded that he was ineligible for the post since he had been raised as a Protestant (an argument that tied up his consecration for a year). Finally, in January 1741 he was ordained bishop in Hammersmith, England. His “diocese” was immense, The district included 10 counties, besides the Channel Islands and even the British possessions in America — chiefly Maryland (which was friendly to Catholics) and Pennsylvania (home of the Quakers) and, incredibly, some West Indian islands.

Bishop Challoner faced many challenges: first of which was the nonstop attempts on his life and that of any and all other Catholic priests (and, when a mob was in a foul mood, any Catholic at all). He moved furtively and often, wrote almost constantly and visited his vast flock in secret, rarely staying in the same place long enough to be found out by the English authorities who sought to kill him.

Remarkably, Bishop Challoner lived out his life and died not a martyr’s, but a natural death at age 89 — ironically in London itself, where the Protestant authorities had so long sought his life (so as to kill him).

While the style, syntax, diction and biblical scholarship of Bishop Challoner may now read as a bit outmoded and dated, it’s an amazing feat that he accomplished it at all — let alone that the Douay-Rheims Bible was the Catholic Bible right up until the 20th century.

Given all this, we can now see why Cardinal Gibbons gave not only his imprimatur, but his kind words to Bishop Challoner when bestowing his ecclesiastical approbation on the American version of the Douay-Rheims Bible.